A Grand Celebration: Musical Serendipity, Distant Memories, and the Preciousness of Tradition. Words on Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan

/There are 48,193 songs in my iTunes library right now. That’s 5,139 albums, 336 gigabytes, and a little over 160 days worth of music. Amongst this staggering (and seemingly-unwieldy) amount of audio lies my most cherished playlist: a 20-hour-long mix creatively titled “December.”

“December” stands alone as a personal treasure, my crown jewel, and the flame that single-handedly ignites my holiday cheer. Grown and cultivated over the course of multiple years, the playlist is a wide-ranging mishmash of various Christmas albums, years-old podcasts, and even some “normal” music that I’ve simply come to associate with the holiday season after multiple years of repeated seasonal listening. My “December” playlist is a testament to curated obsession, self-enforced tradition, and the beauty of the Holiday season. It’s my Christmas spirit encased in a cold, unfeeling .xml file.

The cosmic joke is that, as much as I care for this playlist and the songs contained within it, it’s just that: a collection of random songs. Nobody aside from me would ascribe any particular value to the ordering of these tracks, but I guess that sense of uniqueness is what makes playlists such a sacred musical concept. The other thing that makes playlists so wonderful is their inherent sense of surprise and randomness: the feeling of discovery that comes with stumbling upon a great mix, or the inspiration a single song can carry that inspires you to create one of your own.

Listening to “December” has become a holiday tradition of my own, and as special as the playlist is to me, the entire thing was started by accident. Inspired by a single group of songs and a random iTunes shuffle, this seasonal institution has now ballooned beyond my control and only gotten bigger each year. This is the story of the inception of this playlist, spurred by an album that has severely impacted me and whose sentimentality has become a foundation of my personality.

Discovery

Back in high school music was my escape… not that I had anything to escape from, but music was (and still is) my reality. My one truth. Every morning as I prepared for the day I would let iTunes run through a never-ending shuffle playlist of my music library. They were my last minutes of absorption. My final escape into the realm of sound before venturing out into the world. It was a ceremony that I relished and grew to hold dear over the years.

One cold November morning six years ago, The Shuffle Gods placed a Sufjan Stevens song at the top of the queue. Back then Sufjan was a curiosity; an artist that I’d heard about and always meant to get into, but perpetually found himself on my musical “to-do” list. Thanks to an overly-eager friend, his discography had been sitting on my hard drive, in full, for around a year at that point. In a way, I suppose seeing the full breadth of his work only made diving into his music that much more daunting.

On this fateful day, iTunes DJ (rest in peace) decided that it was finally time for me to hear a Sufjan track and “Oh God, Where Are You Now? (In Pickeral Lake? Pigeon? Marquette? Mackinaw?)” began playing. It was divine intervention. It was exactly what I needed to hear at the moment, and I became transfixed. “Oh God, Where Are You Now” immediately drew me in and hung in my chest like the first deep inhale of a cold winter morning. I was so floored by the song that I needed to hear what came next. I paused the shuffle playlist and embarked upon a search to find the record that this track called home.

This excavation led me to Sufjan’s 2003 album Greetings from Michigan: The Great Lake State which I promptly queued up and let play out. Turns out “Oh God, Where Are You Now?” was track 13 of 15, so while there were only two other songs that followed, I felt compelled to see this record out to its conclusion.

The two songs that came after (“Redford (For Yia-Yia & Pappou)” and “Vito’s Ordination Song”) ended up forming a trio of incredibly potent and deeply-impactful wintery songs that told one coherent and eerie tale.

If the album and songs titles didn’t give it away, Sufjan is not a man who’s concerned with punctuality. While three songs may not seem like much, this final stretch of tracks that close out Michigan ends up coming out to 19 minutes of music. Back in high school, that gave me just enough time to complete my morning routine and get out the door on time.

I became fixated on these three songs, and for the remainder of that year, they became my morning ritual. The soundtrack for two months of sleepy-eyed morning preparation. A sacred custom that I ended up recreating the next year. And the year after that. And the one after that. In fact, for years these three songs were all that I ever listened to from Sufjan’s wide-ranging discography. This 19-minutes of music came to represent the beginning of the holiday season, a near-daily habit of lovingly embracing three folk tracks from an album I hadn’t even listened to all the way through yet.

Obsession

Several years back I realized how silly it was that these three songs were the only ones I’d listened to from Sufjan in earnest. I repeatedly tried to dip my toes into the rest of his discography, and soon “trying Sufjan” became a yearly tradition as well. Year after year I attempted various entry points: whole albums, popular singles, even the rest of Michigan, but nothing ever grabbed me in the same way that those three tracks did.

Then in 2016, it happened: I became obsessed with Sufjan.

I don’t know how it happened or when it did, but it was as if a switch had been flipped in my head. Suddenly everything clicked all at once, and I found myself devouring his discography whole. I had his 5-hour Christmas catalog on repeat. I read every article with his name in the headline. I purchased enough vinyl to create a makeshift shelter. I couldn’t escape from Sufjan Stevens.

By the end of the year, I had racked up nearly 1,000 Sufjan plays, 82% of which occurred between November and December. Every listen up until that year had been relegated almost entirely to the final three songs off Michigan, but suddenly his entire discography had launched itself into the upper stratosphere of my musical consciousness.

In diving through the rest of his albums last winter I now have a firm understanding of who Sufjan Stevens is as an artist and where he sits on the musical spectrum. It turns out that he’s far from the sad, plucky folk singer that I had initially pegged him as. This year I’ve already exceeded last year’s numbers, and #SufjanSeason has become an official holidayin my house. So not only did 2016 signify a tipping point, it represented the beginning of a beautiful, rabid fandom that has opened the door to a new seasonal tradition and hundreds of hours of beautiful music. At the same time, I feel like I’ve only begun to scratch the surface.

Trinity

Sufjan Stevens has arguably made two near-perfect albums: both 2005’s Illinois and 2015’s Carrie & Lowell are widely considered masterpieces of the indie folk singer-songwriter genre. The former is a multi-instrumental masterpiece that showcases an astonishing array of sounds, topics, and textures. The latter is an instrumentally-bare folk album that finds Stevens meditating on life in the wake of his mother’s death. They’re both impeccable records that are worth diving into and worthy of their status as indie essentials, but neither are what this post is for.

Despite recognizing both Illinois and Carrie as “better albums,” I enjoy Michigan more, and I’m still grappling with what that means. While these later albums either swirl and flutter to life with a flurry of baroque instrumentation, or reserve all musicality behind a single veneer of raw guitar and vocals, Michigan lies somewhere in the middle. Packed with frost-covered horns, intimate acoustic guitars, and tenderly-delivered lyrics, Michigan is a chilly, introverted, and thought-provoking record that gently congeals into a cozy wintery panorama.

Like untamed cresting hills covered by a blanket of snow, the surface of Michigan is calm and uniform; a stark, raw, and silent beauty. However, much like that bed of new-fallen snow, once you begin to dig all sorts of unknowable intricacies begin to reveal themselves. It’s a winter wonderland of crisp sounds, all delivered in a singularly-grand package. It’s an album that’s whimsical and but also grounded in dissolution and the pain of existence. Michigan is what it would sound like if the Charlie Brown Christmas special took place in the 2000’s and the characters were all listless 20-somethings without jobs.

If I were to get someone into Sufjan Stevens, I’d still probably point them to either Illinois or Carrie & Lowell (depending on their taste), yet Michigan stands alone as an understated personal favorite of mine for many reasons. Perhaps it’s just thanks to my personal relationship with the album, but accidentally falling into Michigan’s embrace over the course of multiple years has allowed it to embody every warm holiday memory that I’ve ever experienced. It’s my favorite Sufjan record, a wonderful holiday offering, and one of the best in the entire genre.

The remainder of this post is a profile of Michigan and a (near-track-by-track) breakdown of what makes the album worthy of worship. I also adore this record so much that I took it upon myself to create a bunch of mobile wallpapers, so have at them.

Wonderland

Cartoonishly pitched as the first album in a 50-part project covering every state, Michigan is Sufjan Stevens’ third official LP. Preceded by A Sun Came and the electronic Enjoy Your Rabbit, Michigan was far from Sufjan’s first rodeo, but it marked the first time that he seemed to land on a complete and definitive sound. Especially when compared to later albums, Sufjan’s first two outings are great, but end up coming off like a “first attempt” and a left-field electronic diversion that were merely used as stepping stones to later greatness. The entrees meant to hold us over until this: the main course.

Technically a concept album, Michigan is a love letter from Stevens addressed to the state in which he was born and spent a majority of his childhood. The album is a comprehensive look at The Wolverine State, addressing everything from the common points of reference (The Great Lakes, popular sports teams, and overwhelming poverty) to intimate portrayals of what it’s like to live there. All of these tales are sung from the perspective of someone who has a deep, personal, and profound understanding of the area which makes them feel supremely genuine and heartfelt.

Michigan’s first track “Flint (For the Unemployed & Underpaid)” kicks the album off by tackling the exact issue that the state conjures for most people: joblessness. Beginning with a series of arid, ruminating piano chords, Sufjan soon enters singing from a whispered first-person perspective that depicts a dreary future of sadness and uncertainty. Jobless and homeless, the narrator finds himself “pretending to try” but secretly resigned to dying alone. Halfway through the track, a singular trumpet pairs with the established piano melody as Sufjan repeats his death-defying mantra over and over again until the final line is cut off mid-sentence. Shortly after this abrupt end, a hum of ambient noise consumes the song, and the next track begins.

It’s a haunting piece and a stark way to open a record. Most people don’t want to think about losing their job and dying sad, homeless, and alone on the street, yet on Michigan, these ideas are not only commonplace, they’re scene setting. An introduction. The first taste that transports the listener, giving them a sense of place and, hopefully, a similar sense of hopelessness that allows them to empathize with the remainder of the album. This dark opening salvo is contrasted even further by it’s following track “All Good Naysayers, Speak Up! Or Forever Hold Your Peace!” which is a jubilant and bouncy stream-of-consciousness song that explodes with a brassy baroque chamber arrangement.

Here we’re introduced to the “concept” of the album as we realize that every song is sung about the state from different perspectives. This framework allows Stevens to show both the good and bad of Michigan, rapidly shifting from broad sociopolitical issues, then zooming all the way down to hyper-detailed illustrations of interpersonal drama.

Mid-album cuts like “The Upper Peninsula” are down-to-earth groove-centered depictions of rural lower class America. Sufjan finds himself tackling divorce, detachment, and the mundanity of day-to-day life in between Payless Shoes and K-Mart name-drops. Similar sounds are later revisited on songs like “Jacksonville” and “Neighbors” off Illinois but end up focusing on much different song topics.

Even a cursory glance at the album’s credits reveal the shocking amount of instrumentation at play on each of these tracks. Sollum banjo plucks serve as the background on “For the Widows in Paradise, for the Fatherless in Ypsilanti.” Horns and trumpets emerge at unexpected times but are used so precisely that you probably won’t even notice them upon first listen. Instrumental tracks like “Tahquamenon Falls” are jaw-dropping scenic soundscapes that brim with cascading xylophone notes that dance around your head like snowflakes.

Even “traditional” folk arrangements and piano ballads have never been as poignant, soft-spoken, or heartfelt as “Holland” where single isolated piano notes poke up from a whirling frozen mass of sound. Eventually, a backtracked pair of falsetto vocals emerge to echo the song’s chorus, and it paints a vague picture of a couple singing alone in a house with nothing but a guitar, a piano, and each other nearby.

“Detroit, Lift Up Your Weary Head! (Rebuild! Restore! Reconsider!)” is the album’s sprawling ornamental 8-minute centerpiece that begins with a single, rapidly-rung bell. Soon a piano enters the mix, then a guitar, then Sufjan himself. The entire track builds around the beat of that bell until dozens of individual instruments all combine into this massive, extravagant, and decadent force of nature.

Things get personal on the banjo-plucked “Romulus” as Sufjan recounts several strained interactions with his mother even though he recognizes that he would do no better in her position. This dynamic would later be revisited and fully-addressed on Carrie & Lowell, but, “Romulus” is still a striking portrayal of a frayed relationship as well as the joys and frustrations that come along with family.

Finally, “Sleeping Bear, Sault Saint Marie” is an epic, swelling biblical track that escalates in delicate crescendos that all climax into one massive, breathtaking wall of sound. Accompanied by Megan Slaboda and Elin Smith, this late-album cut features an awe-inspiring instrumental mixture of organs, cymbals, and warm brass instruments. A careful and measured track that slows down to nothing then explodes to life.

The entire album sounds like a snow-covered log cabin. It feels like a warm cup of hot chocolate on a cold, grey, rainy day. It smells like a freshly-cut noble fir. It tastes like a home-cooked bowl of soup. It’s the warm wool blanket enveloping your body. The cinnamon-sprinkled cookies that just came out of the oven. The glowing lights that dance and twinkle above your head. It’s musical soul food. It’s wholesome and full-bodied music that makes me want to be a better person. It’s absolutely flawless.

Despair and Grace

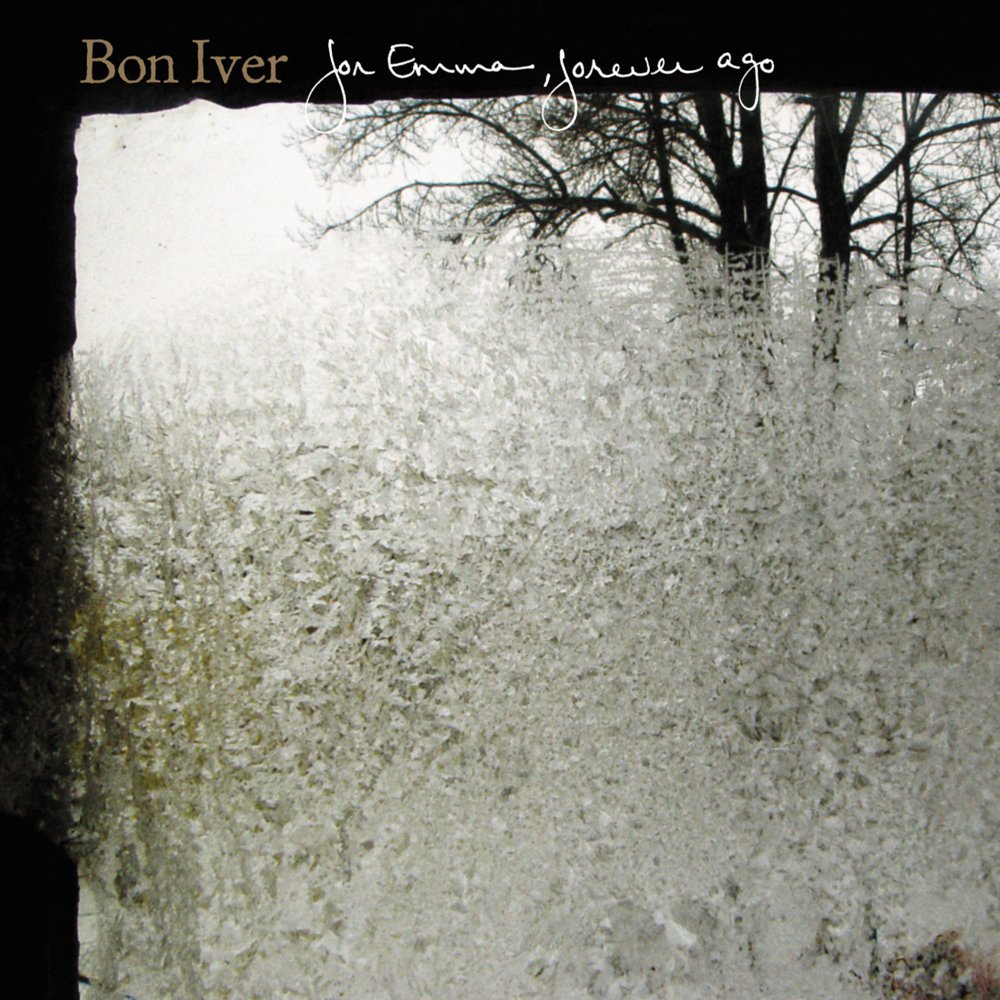

Circling back to the jumping off point of this post: I still remember hearing “Oh God, Where Are You Now?” for the first time and being struck with a strange sense of deja-vu. The track instantly evoked something deep inside of me. It made me feel everything that I’ve described up until this point and also came with a strange sense of familiarity. It felt like a piece of a past life that I’d lost and now recovered. I carefully studied the album artwork, and it looked like a long-lost Christmas album. The majestic snow-covered pine tree, the elegant deer, the warm red lettering, all captured in Laura Normandin’s beautiful brush strokes over a rich parchment. Everything about Michigan felt picture-perfect.

After 47 minutes of splendor, the most brilliant moment of Michigan comes with its final three-song stretch that winds from “Oh God, Where Are You Now? (In Pickerel Lake? Pigeon? Marquette? Mackinaw?)“ to “Redford (For Yia-Yia & Pappou)” and “Vito’s Ordination Song.” These three songs stand on their own as a singularly-impactful and world-shaping experience that are intertwined with some of the fondest, warmest, and most intimate memories of my entire life.

“Oh God, Where Are You Now?” begins with Stevens addressing God directly. Paired with a barely-distorted guitar line and a gently-played piano, our narrator finds himself questioning his faith as he whispers the title of the track and begs for God to touch him. Sufjan’s voice intertwines with a hushed group of backup singers comprised of Megan Slaboda, John Ringhofer, and Elin Smith as they collectively ask “Would the righteous still remain? / Would my body stay the same?”

Soon all four vocalists combine into one extraordinary force, all singing over a sparse, mounting piano melody and finger-plucked guitar. Midway through the song, after repeating the same set of heaven-bound lines, all of the vocalists break into a makeshift wordless chorus as they sing along to the now-established tune set by the piano.

All of the instruments all flicker and shimmer as if being played from a distant memory. The piano is patient and carefully tapped. The guitar gleams and quivers, faint and serene. You can hear ambient noise trickling in between the quiet pauses as if the entire of the studio was breathing and coming to life at that moment.

Near the end of the track, Sufjan’s vocals become more prominent and press up against the backup singers as they all revisit the chorus for a third time. Soon a mighty brush of cymbals erupt. Horns emerge from the corners of the mix and play along with the group’s established melody. The piano picks back up, newly energized and boisterous. Soon another pair of horns emerge and add splashes of light to the song’s bigger picture. Every element is working in tandem, taking turns, all adding on to the song’s resounding and soul-affirming chant of “La da da, da da da.”

Then everything quiets to a hum. The horns and cymbals carry the song out with long, colorful streaks. It’s both somber and gorgeous. It’s warm and cozy, a melody that you can slip away into and tuck under yourself like a blanket. A massive tide consuming your soul at a glacial pace. Then, after nine minutes and 24 seconds, it’s gone. Silence.

Picking up exactly where “Oh God” left off, the very next thing the listeners hears are the timbred piano strikes of “Redford (For Yia-Yia & Pappou).” You can make out the distant wooden creak of a chair or a floorboard, and again, your mind is transported back to a remote snow-covered cabin in the middle of the woods. Far-off vocals echo through the top of the mix like specters haunting the lone pianist. Still, the melody continues, the reflective musician is barreling towards his destination with more confidence and determination than ever before.

In the final seconds, Redford’s piano ceases and the ethereal vocals make their last wail before being claimed by static silence, and then the song ends. “Redford” is a momentary meditation before the album’s final impact. The first part of a one-two punch. A connecting piece that serves as the bridge between the album’s two defining works.

Next, the final track unveils itself. “Vito’s Ordination Song” begins with an elongated and heavy organ chord, as if the pianist from the last song had suddenly been brought back to life. It sounds wholesome and church-like, evoking the feeling of both a funeral and a sermon.

Sufjan returns from the instrumental abyss and quietly recalls “I always knew you / In your mother’s arms.” Swiftly navigating toward noisy imagery of marriage, happiness, and warmth as the organ continues beneath his deliberate vocals. Then after a three-song absence, a set of drums enter the fray. Booming in comparison to the sense of quiet softness we’ve been basking in over the past 15 minutes, the drum keeps time while making way for a subtle horn arrangement and heart-beat-like organ passage.

The album’s cast of backup vocalists rejoin Sufjan for one final time, duetting and echoing the same sentiments as the song’s first verse but now full and exploding with liveliness. The group of singers land gracefully upon a final chorus that ferries us along for the remaining four minutes of the album: “Rest in my arms / Sleep in my bed / There’s a design / To what I did and said.”

It’s soul-crushing, heartbreaking, and beautiful. It evokes such a varied range of emotions in me that it feels truly herculean to into words. It is winter. It is Christmas. It is heavenly. It is transcendental. It is every happy moment that I’ve ever experienced over the past decade. The soundtrack to the warm memories that exist only in my head. It’s the reflection of my entire life.

The same way that you feel when you gather with your family to watch that beloved Christmas movie. The way that you feel in the embrace of a loved one. The feeling you get when leafing through an old photo album of memories now long-past. The people you spent your life with. The recipes you made together. The ones that never got to share them. It is love. It is life. It is loss. It is everything and nothing more.

These songs make me unspeakably thankful for the life that I’ve lived, and the life I’m going to lead. They are truly perfect pieces of art. To completely break the flow, I initially wrote this while listening to Michigan for the first time this year, and teared up as I wrote this… Definitely a first for this blog.

In many ways, this three-song stretch is the reason that I created this website. A location for me to document, wholly and lovingly the things that bring me unimaginable joy. The beautiful thing is, everyone has their own three-song stretch. Some little thing that makes you happy. Maybe it’s something that nobody else knows about. Perhaps it’s so esoteric that it feels silly to share with anyone, even those closest to you. But I encourage you to share it. It’s something that you hold dearer than anything else in life. A genuine treasure. A piece of your soul crystallized externally. For me, that’s Michigan. It’s a work of art, a masterpiece, and my life.