Smashing Pumpkins Misunderstood Madness of Machina: 25 Years Later

/Photo by David Williams

In the spring of 1999, Billy Corgan plotted a scheme to snatch back the title of rock n’ roll king. This was coming just a year after a turbulent reception to his band’s fourth studio record, the unjustly maligned Adore. The public, it seemed, was not ready for The Smashing Pumpkins to turn their signature stadium-level rock into an intimate, ballad-heavy experience with an abundance of synths. The album failed to reach the sky-high peak of Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, which was an impossible feat to achieve (that record sold so much it went diamond), especially given the electronic-goth pivot they executed on Adore. The Pumpkins became victims of their own success; the number one band of the mid-’90s was hit with devastating adversity heading into the new millennium.

Around this era, music shifted away from the grunge movement that defined the early part of the decade. In many ways, this was rock music’s last gasp at the forefront of the cultural zeitgeist. Bands like Pearl Jam and Nirvana were replaced by boy bands, hip-hop, and a fresh wave of aggro rock music dubbed nu-metal. TRL was my barometer for culture at this time: every day when I got home from school, I’d tune in at 4 PM Central Time to watch Carson Daly introduce videos from Britney Spears, NSYNC, Jay-Z, and Limp Bizkit. The bands of the early ‘90s were essentially pushed aside like Brussels sprouts at the kids’ table during Thanksgiving.

Rock music was in an undeniable state of transition during this period, with nu-metal leading the charge as a louder, angrier, and more aggressive offering. Groups like Limp Bizkit, Deftones, Kid Rock, Korn, and Rob Zombie were the bands that people wanted to listen to as the Y2K era approached. For a super-specific example, consider the entrance music of WWE legend The Undertaker. When he had his biker gimmick, The Undertaker introduced this era by coming out to Kid Rock’s “American Bad Ass,” but by the time the new millennium rolled around, he shifted to Limp Bizkit’s “Rollin’ (Air Raid Vehicle).” And don’t even get me started on the Mission: Impossible 2 soundtrack; if someone wanted to know what this era sounded like, just go listen to that album. It didn’t matter what the content was culturally; if a studio wanted commercially friendly rock songs attached to their product, they were going to be knocking on a nu-metal band’s doors.

So, going back to the Pumpkins, Billy Corgan wanted to compete as if he were a top-tier athlete, testing his powers against the young guns while also aiming to make one last great record as a “fuck you” to the music industry as a whole. Feeling scorned by executives, critics, and even his own fanbase who rejected the previous record, Corgan began to conceive of a new album – a collection of songs so great that it would prove them all wrong.

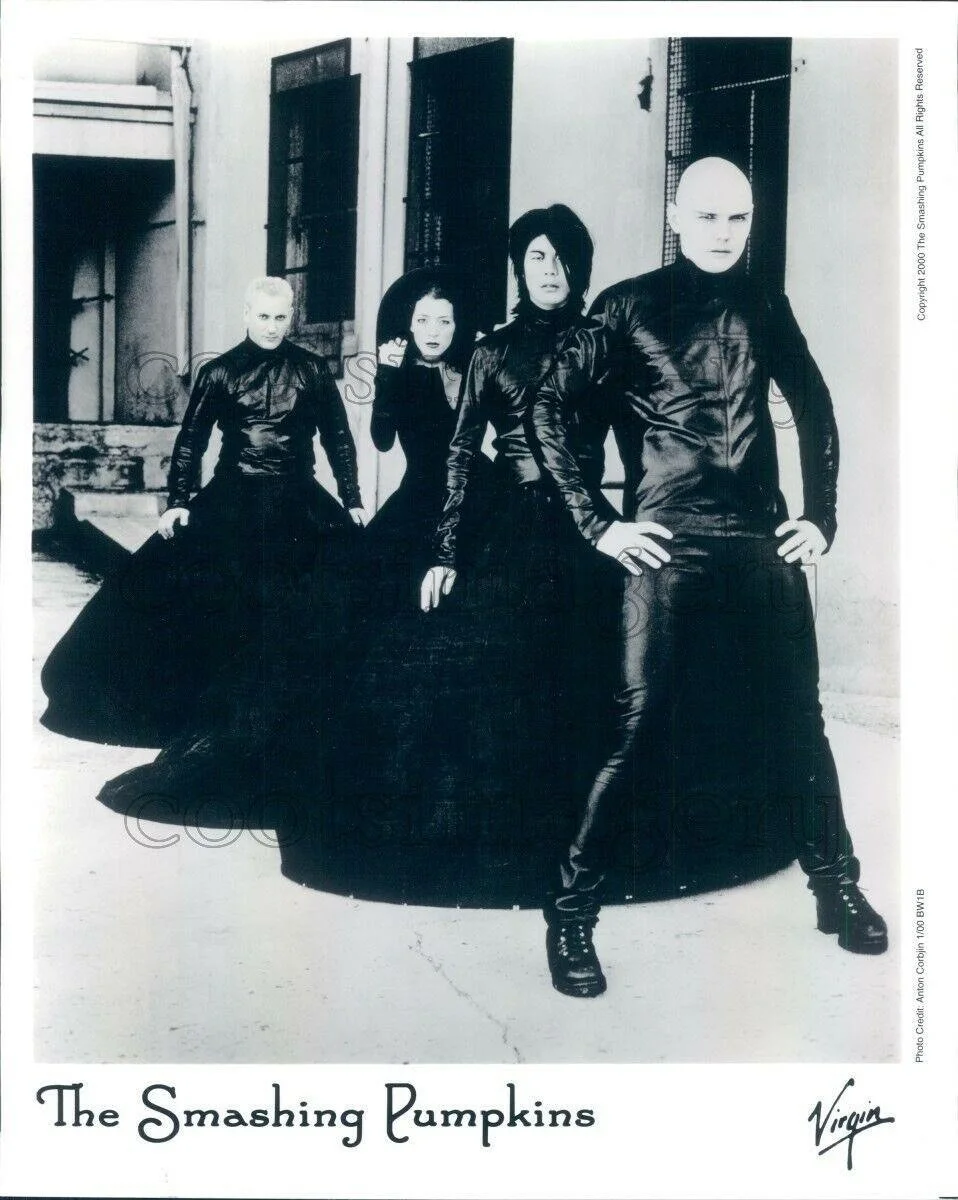

The Smashing Pumpkins, Circa 2000

But first, to even begin working toward this goal restoring the order of rock supremacy, Corgan needed drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, his hired muscle, back into the mix. Chamberlin is the merciless force that takes no prisoners behind the sticks. Songs like “Jellybelly,” “Geek U.S.A.,” and “An Ode to No One” showcase just what kind of Tasmanian Devil he truly became. Chamberlin combined his jazz background with a late-70s rock style that, I can attest after seeing his live performance, is truly a one-of-a-kind experience. Unfortunately, Chamberlin was exiled from the Pumpkins in 1996 for rampant drug use, so once he showed the ability to lead a clean lifestyle in the three years that followed, he was reinstated. Corgan said it best in an infamous Q Magazine interview that dubbed him THE RUDEST MAN IN ROCK: “If you want to know what Jimmy brings back to the band, then listen to Adore and this record back to back. It speaks for itself.”

Once Chamberlin returned, Smashing Pumpkins had all four original members back and ready to rock. James Iha, who is the Robin to Corgan’s Batman, has a reserved persona, always seemingly lurking in the shadows away from the attention of the spotlight. Iha excelled at bringing a more atmospheric ambiance to Corgan’s devastating power riffs. Meanwhile, bass player D’Arcy Wretzky has the kind of cool factor that you can only be born with. Known for her signature bleach blonde hair and nonchalant attitude, she brought an edge to the Pumpkins that no one can put an exact measure to. Wretzky was also the tastemaker of the band, where songs would often be run by her to see if they would work on records.

Photo by David Williams

Once reassembled, the band was off to the races, breaking ground on a concept album titled Machina / The Machines of God. The thought was for all the band members to play exaggerated caricatures of themselves, becoming the cartoon-like characters the public and critics viewed them as. The story of the record would revolve around a rock superstar named Zero (based on Corgan) who heard the voice of God, then renamed himself Glass and further renamed his band The Machines of God. The fans of the band are also known as the “Ghost Children.” Are you still with me? Good! Whether you think this plot is insanely convoluted or insanely brilliant, you have to admire the ambition of artists swinging for the fences with max power regardless of the outcome.

The Smashing Pumpkins, around this time, were the poster child for dysfunction. Right when the band reunited, everyone appeared to be in a harmonious kumbaya state, and the ship had finally been righted. I know their fans had to be thinking, “Ok, here we go! We’re about to get another Pumpkins classic!” Instead, something else was arriving in the shape of a neutron bomb flying in seemingly out of nowhere. Wretzky leaves the band before the recording is finished, never to return again, seemingly crushing the concept before it ever even began. When Corgan spoke to Q, he said, “I’m not going to talk about D’Arcy; she left for reasons more complicated than any single answer could hope to cover. So, I’m not going to get into that. It’s a private matter.”

In the music business, especially for a major label like Virgin, the show must go on; an album still needs to be recorded. What came out of those recordings is some of The Smashing Pumpkins’ most intriguing work to date. Opening track “The Everlasting Gaze,” which also served as the lead single from Machina, is one of my favorite songs in their entire catalog. The main attraction is the infectious cyber-metal guitar riffs that find a delicate tightrope balance of power and catchiness. Corgan repeats the opening lyrics “You know I’m not dead” nonstop as if he’s Freddy Krueger in a slasher film. No matter how hard you try, you just can’t kill the man. On top of that, when you throw in the addicting, can’t-take-my-eyes-off-it music video by Grammy award-winning director Jonas Åkerlund, the song is a can’t-miss experience. Go ahead and take a peek for yourself. This had all the ingredients for a timeless video; it’s goth, metal, theatrical, and has a leprechaun-green carpet, what more can you ask for?

Another classic that derived from this era of the Pumpkins was “Stand Inside Your Love.” This is another insane, visually entertaining music video, shot entirely in black and white and inspired by an Oscar Wilde play from 1891. The song has a new wave vibe similar to that of another Pumpkins mega-classic, “1979.” Does anyone know what “standing inside someone’s love means?” It doesn’t matter because the song is superb and is a pop hit.

One thing I appreciate about Machina, regardless of whatever dysfunction or controversy surrounded the band, was how they went for it. The Pumpkins easily could have folded and called it a day after a member left the band, but there are some seriously underrated pop songs here when you peel back the layers. “I Of The Mourning,” which, in my estimation, should have been the third single, accompanied by a music video, was essentially made for radio airwaves with that earwormy chorus. “This Time” is Corgan’s love song to the band, singing in only the way he can, “And yet it haunts me so / What we are letting go / Our spell is broken,” the words his heartfelt ode to a band that was actively being ripped to shreds. “With Every Light” is the gentlest song on Machina, and I believe that if it came out today, it would have a cult following, given how much new music coming out seems to borrow from the same spirit of this track.

Machina was caught between a rock and a hard place, regardless of the quality of the music. The public moved on from the alternative sound in the year 2000, and the convoluted concept didn’t help either. I don’t think the idea of the album was conveyed clearly enough for people to wrap their minds around while listening. Eight years after the release, Corgan reflected on the record’s failures, stating, “I think the combination of the band breaking up during that record, D’arcy leaving the band… Korn was huge at the time, Limp Bizkit was huge at the time, so the album wasn’t heavy enough. It wasn’t alternative enough; it was sort of caught between the cracks. And it was a concept record, which nobody understood. So the combination of those elements was a career-killer… Adore didn’t alienate the audience; they were just sort of like, ‘Oh, it’s not the record I want.’ Machina alienated people.”

In addition to all this, I can’t stress enough just how much Corgan had worn out his welcome with the press. From the band’s own in-fighting to the combative nature of his interviews, he didn’t do himself any favors. Goodwill was as good as eroded leading up to Machina, as Corgan would often give interviews with a played-up, standoffish persona to unsuspecting journalists. I’m a humongous wrestling fan, so I can appreciate Corgan relishing in the art of going kayfabe (presenting a staged performance as genuine or authentic), but you can’t treat an interview with Rolling Stone as if you’re cutting a promo on Stone Cold Steve Austin. That’s a recipe for a disaster, which is exactly what happened with the media on this album cycle.

Machina presents some of the most jarring “what ifs” in this era of music. What if D’Arcy never left the group? What if the story were clearer and more concise? What if Corgan got his wish and this were a double LP like Mellon Collie? Virgin Records denied Corgan this extravagance, citing the poor record sales of Adore. There was so much carryover material from Machina that there was no place to put it, so the band deployed a guerrilla marketing campaign for what would become known as Machina II. Only twenty-five vinyl copies were made and distributed to friends, with the sole mission of passing them along to the internet. That’s some forward-thinking views on online piracy for the twenty-first century to say the least.

What would become of Machina II was an artistic blend of synth-goth, dream-pop, and industrial heavy metal. This was a proper swan song for the initial run of the Pumpkins. If they had been granted the double-album treatment, I think this collection would have solidified them with one last classic to their name before bowing out in the year 2000.

Epilogue

The Machina era of The Smashing Pumpkins has reached its 25th Anniversary, and to celebrate this achievement, Billy Corgan has released a deluxe vinyl box set that collects the full story in one place. No longer do fans have to painstakingly agonize over what order the original song concepts would have been. The vinyl dubbed Machina — Aranea Alba Edition is forty-eight songs in length, complete with thirty-two bonus tracks of demos, outtakes, and live performances for the low-low price of three hundred and ninety-five dollars. If, like most folks, you find that this price is too rich for your blood, I’m sure this will hit streaming services soon enough. The year 2000 was a complicated, befuddling, and downtrodden end for the original Pumpkins lineup, but I’m happy to see that, slowly, more people are recognizing the artistic beauty of Machina, even twenty-five years later. Better late than never.

David is a content mercenary based in Chicago. He’s also a freelance writer specializing in music, movies, and culture. His hidden talents are his mid-range jump shot and the ability to always be able to tell when someone is uncomfortable at a party. You can find him scrolling away on Instagram @davidmwill89, Twitter @Cobretti24, or Medium @davidmwms.