It Gets Brown: Swim Into The Sound's Guide to Ween

/Every fandom begins somewhere. No matter what medium, format, time or place, everything you love can be traced back to a single moment when everything clicked into place. While we’re not always conscious of these origins, the fandoms that we can trace back to inception often feel so much more visceral and noteworthy than the ones that unfold gradually. Back in 2012 I heard a song that single-handedly sparked a fandom, ignited an obsession, and sent me on a years-long artistic exploration that remains one of the most twisted and wild experiences of my entire life.

The song in question was “If You Could Save Yourself (You’d Save Us All)” which was placed at the end of the 234th episode of a comedy podcast called Uhh Yeah Dude. I found myself transfixed by the song as I let the remaining minutes of the hour-long podcast play out on my dark gray iPod Classic. Mistified with a strange sense of familiarity, I clicked over to the information screen of my device to find the name of the band that performed the song. Ween. By the time that the ballad had faded out, I felt compelled to research the group further, and I quickly discovered why the song felt so familiar: I’d been listening to Ween since I was a child.

Thank You, Stephen Hillenburg

It’s already weird to think about what music fandom was like in a pre-internet world. As someone born in 1993, I feel like I’m part of the last generation to experience the “entertainment oasis” that came with only having access to the physical media that’s on-hand. When you were a kid with five CDs, endless free time, and zero taste you’d find yourself listening to the same things over and over again without thinking twice.

Now that the internet is pervasive enough, platforms like iTunes, Youtube, and Spotify have made the entertainment oasis a thing of the past. These services have changed our world so rapidly that it’s interesting to cast your mind back to the time before they existed… though there’s still no accounting for taste.

One of the first CDs that I ever owned was Spongebob Squarepants - Original Theme Highlights which is a 12-minute compilation of songs from the first two seasons of the Nickelodeon show. This album, along with Eiffel 65, Sum 41, U2, and Spider-Man comprised the highly-unlikely and undeniably-absurd quintet of albums that made up my first CD collection. Looking at this list now, it seems inexplicable and extraordinarily embarrassing (especially given how many times I listened to each of these) but like I said, being 8 in 2001 was weird.

I listened to those five albums enough to memorize every one of them word for word because I had nothing else. Of the Spongebob record’s 12-minute running time, 61 seconds are taken up by a Ween song called “Loop De Loop.” I didn’t have last.fm then, but I would hazard a guess that I listened to this song at least a few hundred times throughout my childhood.

Ween resurfaced within the Spongebob oeuvre several years later when “Ocean Man” was used in The Spongebob Squarepants Movie as the film’s closing credits song. I didn’t listen to that movie’s OST nearly as much as I did Original Theme Highlights, but I still heard “Ocean Man” enough times for the song to make a lasting impact on me.

Thanks to Stephen Hillenburg’s apparent fandom of the band, I found myself overwhelmingly susceptible to nostalgia when I heard “If You Could Save Yourself” close out that podcast in 2012. This childhood band had wormed their way back into my musical consciousness in the most unexpected way possible over one decade after I was first exposed to them. I ended up diving into Ween that same year, and the band proved themselves to be a powerful creative force that I desperately needed in my life at that time.

For the sake of not turning away any more potential readers with further hyper-specific personal details, I’m now going to remove myself from this narrative as much as possible and formally introduce you to the band called Ween.

The History

Ween is a band from New Hope, Pennsylvania comprised of Aaron Freeman and Mickey Melchiondo Jr. Formed in 1984, the two met in a middle-school typing class and quickly bonded over their shared love of music and drugs. Eventually, this unlikely pair of slackers set out to record songs of their own using nothing but the cheap-ass equipment they had on-hand. Donning the personas of two brothers, Freeman and Melchiondo became Gene and Dean Ween respectively. Together they combined to form Ween, and the duo began crafting unrelentingly-goofy and drugged-out lo-fi indie music that was “designed to be obnoxious.”

For five years, the pair recorded a series of cassette-based releases in which Gene sang, Dean played guitar, and a pre-recorded beat kept time. Occasionally joined by Chris Williams on bass as “Mean Ween” the group quickly garnered a cult following that was drawn to the band’s absurdist approach to music, songwriting, and life.

By 1990 Ween had released a (relatively) polished debut that culled the best of their cassette tape-era tracks into one commercial full-length. Within one decade of their inception, they were four records deep, playing with a full band, and hailed as one of the weirdest acts in indie. Through sheer persistence, Ween has managed to cultivate and maintain a hyper-dedicated fanbase that simultaneously allowed for the group’s continued success while also allowing them to fly under the radar.

They’ve had a few one-off hits throughout the years that gained them mainstream visibility, but for the most part, Ween has primarily remained a cult band with a long list of semi-impenetrable albums, and an even longer list of b-sides and bootlegs. While the history is important to know, these are just the (very) broad brush strokes of a band that’s had a 3+ decade career. More important than the timelines and the drama is the actual music, so let’s talk about that.

The Sound

The reason I felt the need to create this guide is a simple one: Ween is one of my favorite bands of all time. Unfortunately, as incredible as their music is, they don’t go out of their way to make it particularly accessible. While there’s a slight “barrier to entry” to most of their records, they’re a band that’s worth the effort. Additionally, once their music does click, it’s actually hard to be a “casual” Ween fan because their work is so vast and diverse that each song becomes a rewarding adventure that stands on its own. They’re a group that practically begs to be worshiped, but they definitely test your faith in the beginning.

In spite of (or perhaps because of) their extensive body of music, it’s often hard for would-be fans to find a proper entry point into the group’s work. That goes double for an outsider who jumps into Ween’s discography with no primer or guidance from a long-time fan. In a way, you have to “build up a tolerance” to their sound in order to fully-realize the brilliance of their earlier albums. It’s a long and twisted journey, but it’s worth taking.

Perfectly described by Hank Shteamer as “pan-stylistic,” Ween is a genre bender in the truest sense. Never limiting themselves to one sound or concept, the members of Ween actively embrace just about every type of music under the sun. This is another reason why it can be hard to get into the band. Because they play a little bit of everything, any given Ween album can contain up to a dozen different sounds, accents, and goofy lyrics, so knowing where to start can vary depending on the listener’s taste.

What’s impressive is not the fact that Ween can play every genre, but that they can play every genre competently. Within minutes they can jump from hard rock to country to funk to piano balladry, all without breaking a sweat. More importantly, this isn’t done in some half-assed ironic way, every genre that Ween tackles is done in a full, loving, and complete embrace of the sounds they’re emulating. It’s a universal reverence for art, music, and creativity.

It’s not that their style is hard to define, it’s that they’ve invented their own style.

Early on in their partnership, Gene and Dean coined the term “Brown” to describe the band’s sound. Explained as “fucked up, but in a good way,” Brown is the all-encompassing term (and a major piece of mythology) used by the band and its fans when discussing the music. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but you’ll know it when you hear it. Brown knows no genres. Brown knows no limits.

The most frequent comparisons made are typically the Grateful Dead or Phish, but even those do Ween a disservice because it makes them sound like a jam band which they are decidedly not. A more apt comparison would be to Frank Zappa or Captain Beefheart but even then, Ween stands alone from each of these artists as a unique entity.

In fact, the closest reference point to Ween may not be music at all, but the broader concept of Gonzo. Unedited, profane, druggy, sarcastic, personable, exaggerated, humorous, and eclectic. All of these words are simultaneously accurate and describe Ween’s music to a T.

Jumping back to why I felt the need to create this guide: Ween’s early stuff is rough and dissonant, and their later material can be more serious and spotty. As a result, they’re a band that benefits significantly from a specific listening order if you genuinely want to sink your teeth into them. If you don’t have a Ween fan in your life, I’m here to be your faithful Ween shaman. This is an album-by-album guide, telling you what to listen to, providing context, and walking you through each of the group’s core works.

I’ve successfully used this same path to turn two other people into fans, and (for the most part) it follows a largely agreed-upon “canon” according to other hardcore fans. I’ve merely composed the words to go along with each record in an attempt to explain why each one is special. While I’m always a proponent of listening to albums in whole, I’ve also selected three cuts from each LP that offer brief glimpses into the variety of sounds and genres contained within each record. You can check out these select tracks in this Spotify Playlist if you’d like, but I’d still say each of these albums are worth listening to in-full if you have the time.

Now that we’ve got all that out of the way let’s dive in.

1 |The Mollusk (1997)

By far the most commonly-agreed-upon starting point amongst Ween fans, The Mollusk strikes a perfect balance between polished accessibility, outlandish weirdness, and objective greatness.

Opener “I’m Dancing in the Show Tonight” immediately sets the tone for the record, kicking things off with a jaunty tuba-filled track featuring multiple distorted vocal takes all simultaneously fighting for the listener’s attention. It’s a curveball right off the bat, but it’s also just short enough that the listener may write it off as a one-off intro track.

From there, the songs range from woozy psychedelia on “Mutilated Lips” and “It’s Gonna Be (Alright)” to rip-ass rock on “I’ll Be Your Jonny On The Spot.” There are straight-up novelty songs like “Waving My Dick In The Wind” and “Blarney Stone,” but even the weirdest tracks here serve to add an additional layer onto the record’s barnacle-ridden Celtic aesthetic.

Most notably, the aforementioned “Ocean Man” was expertly-deployed as the credits song to 2004’s Spongebob Squarepants Movie and probably remains the single best entry point to the rest of the band’s work. Perfectly singable, wonderfully upbeat, and just weird enough to feel “Weeny,” “Ocean Man” will forever be the definitive entry-level Ween song.

2 |Quebec (2003)

Shiny, high-flying, and shockingly mature, Quebec is a melancholic sample platter of everything Ween had mastered after nearly two decades of music creation.

Three years after one of the most polished records in their discography, Ween went back to the drawing board and decided to throw themselves headlong back into the absurdity that got them where they were. Mixing their early psychedelia with very adult-like sadness and grounded realism, Ween managed to craft one of the most well-rounded records in their entire discography.

Featuring some of the most stoner-ready tracks in their discography alongside some of the most shred-worthy, Quebec is a testament to the group’s staying power. With 15 tracks stretched over 55 minutes, Quebec helped the band find a second wind through “Transdermal Celebration” which became a relative commercial success. Occasionally the scope swells to grand operatic scales on songs like “If You Could Save Yourself” only to rapidly shift back to childish goof on songs like “Hey There Fancypants.” In jumping between these vastly different voices, the band fleshed out their sonic scale and landed on a formula that cemented their position as all-time greats.

3 |Chocolate and Cheese (1994)

Chocolate and Cheese takes the variation of Quebec, adds the outlandishness of Mollusk, and then jumps five steps further into humor.

Probably the earliest “accessible” album of the band’s career, Chocolate and Cheese is often cited as an alternative starting point to Mollusk mainly because it bears more of the band’s trademarked comedy and goofiness throughout. Unfortunately, this album is also the tipping point for some fans in this early part of the Ween journey because if you don’t like this record, it’s unlikely you’ll enjoy anything that comes after it.

While the production on Chocolate and Cheese is slightly more limited than Quebec, this record contains the most ideas per square inch than any other record in the band’s career. Some later albums are more “out there,” but nearly every track on C&C stands alone as a well-polished, fleshed-out, and fully-realized concept. Not necessarily the “weirdest” album in their repertoire, but when every track is different, you never have the chance to be bored.

“Voodoo Lady” is a groovy tongue-twister of a bop, “Take Me Away” is a hard-charging opener, and “Mister Would You Please Help My Pony?” is yet another ‘childlike’ Ween track that, if it weren’t for a few scattered “fucks,” probably could have fit in on an episode of Spongebob. There’s a little something for everyone, and no song resembles anything close to the one that came before it.

The definitive song on Chocolate & Cheese comes in the form of its 13th track “Buenos Tardes Amigo” which weaves an epic 7-minute spaghetti western tale of drama and betrayal. It’s a passionate track that’s impeccably-delivered with a jaw-dropping guitar solo centerpiece, all of which makes for a narrative that’s deserving of your full attention. The fact that it’s followed up by a track called “The HIV Song” is a quintessential Ween move.

While the Mollusk, Quebec, and Cheese make up for a perfect triumvirate of “Beginning Ween Albums,” we now take a few steps further into obscurity with the middle three records in this guide. Featuring later-career albums that are slightly less accessible, and just a little spottier, we now find ourselves in the depths of it all.

4 |White Pepper (2000)

White Pepper is Ween’s most impeccably-produced album featuring a 40-minute collection of powerful would-be radio hits.

Following the (again, relative) success of The Mollusk, the band went back into the studio for several years and emerged in 2000 with White Pepper which represented a noticeable slide towards cleaner production, shockingly-polished instrumentals, and decidedly more thoughtful lyrics.

Perhaps fittingly, there is almost nothing “Brown” about White Pepper, even still, the group manages to find moments of grit with songs like “Stroker Ace” and “The Grobe.” Conversely, there are also uncharacteristically breezy songs like “Even If You Don’t” and “The Flutes of Chi,” but even these objectively-pleasant songs are undercut with a hint of unmistakably Ween-ey humor once you begin to analyze them past the surface level.

The best example of this is “Bananas and Blow” which sounds like a pitch-perfect Jimmy Buffet song if he wasn’t so worried about turning off his listeners with blatant casual drug use. This track features “Buenas Tardes”-esque southern guitar work, female backing vocals, and an island-worthy rhythm section. The exotic instrumental is paired with a wispily-delivered and heavily-accented delivery by Gener depicting an isolated potassium-rich drug bender. Indeed a paragon of the Ween dynamic.

5 |12 Golden Country Greats (1996)

12 Golden Country Greats is precisely what it sounds like: a collection of wonderfully-creative and surprisingly-earnest original country tunes.

Even if you’re not a country fan, the way that Ween finds a way to impress their signature sound on ten songs of differing speeds is worth witnessing. From high-speed hoedowns (“Pretty Girl” and “Japanese Cowboy”) to remorseful bluesy tracks (“I’m Holding You” and “You Were The Fool”) 12 Golden Country Greats hits every measure with pitch-perfect accuracy and surprising grace.

Most impressively, “Piss Up A Rope” has managed to worm its way into all-time classic status as one of the group’s live staples. On the same tip, the heartache-inducing “Fluffy” represents the exact tonal inverse of “Piss Up A Rope,” but still manages to strike a balance between these two mid-nineties goofballs and one of America’s oldest music genres.

It’s not the album that you’d expect following the slight commercial success of Chocolate & Cheese two years earlier, but that’s what’s great about Ween: every move is unexpected, yet they manage to pull it off flawlessly. While 12 Golden Country Greats is obviously as diverse as any of their other records, the band manages to make a full-album genre experiment look like a cake walk.

6 | La Cucaracha (2007)

La Cucaracha is the Ween’s carefree late-career album and the long-form reflection of a decades-long journey.

Already over a decade old at the time of this writing, La Cucaracha is, sadly, Ween’s latest record. While they’ve had a few public brakes and even a full-on hiatus in recent years, it’s still surprising that La Cucaracha is the last we’ve heard from the band in any official capacity. I say that both because I want new songs, but also because this album is a bit of a sour note to go out on. I almost considered cutting it for the sake of the listener experience, but eventually, I decided that I want this list to be comprehensive.

At the end of the day, La Cucaracha isn’t a bad record, it just feels less inventive than everything else that’s come before it. While there are still some scattered highlights like “Your Party” and “Fiesta” there isn’t much to write home about on La Cucaracha, at least nothing that you couldn’t get from earlier releases.

The album’s single most significant contribution comes in the form of “Woman and Man” which is an 11-minute epic that erupts into a ferocious and densely-packed 8-minute instrumental jam.

After a slightly saggier middle section, we’ve reached the final trio of Ween albums. This is where things get weird. This is where things get great. This is why the previous albums were necessary. The build-up is worth it because the payoff is beautiful. In this final grouping of albums, we fully-descend into Brown, and everything will begin to make sense. Brace yourselves.

7 |GodWeenSatan: The Oneness (1990)

GodWeenSatan is the group’s full-album unveiling to the world with over two dozen songs of lovesick mania.

On Ween’s debut, we find a surprisingly-accessible early version of the band that is already brimming over the top with outlandish ideas. Clocking in at 76 minutes with 29 tracks, nearly every song on here hovers around the 2-minute range which allows the band to showcase their wide variety of genres, voices, and whacky lyrics. Throughout the LP the duo finds themselves quickly springing from one idea to the next with no warning, no regard for the listener, and no concern for perceived “cohesiveness.” Most songs end in improvised conversations, explosions of laughter, or simply incoherent screaming. It just sounds like two teenagers who are having making music… because that’s exactly what it is.

While there’s still more genre variation than any other band, the group occasionally finds themselves visiting similar sounds throughout the record. “You Fucked Up” and “Common Bitch” are both explosive balls-out rock tracks. “I’m In The Mood To Move” and “Blackjack” are pitch-shifted stream-of-consciousness ramblings/word associations placed over minimalistic instrumentation. “Cold and Wet” and “Nan” both find Gener adopting an Adam Sandler-esque voice over rolling bluey riffs.

Meanwhile one of the album’s most ‘traditionally pleasant’ songs “Don’t Laugh (I Love You)” ends in one minute of off-puttingly-loud screeching and uncontrollable laughter, and if there’s a better encapsulation of Ween than that dichotomy, I don’t know it.

Despite how early on it is in their career, it’s incredible how polished and well-produced these tracks sound thanks to a 2001 remaster. While GodWeenSatan has a few rough edges, you can already feel the band laying down the framework for their future releases, plus the tunes are absolutely undeniable. It will overstimulate your senses.

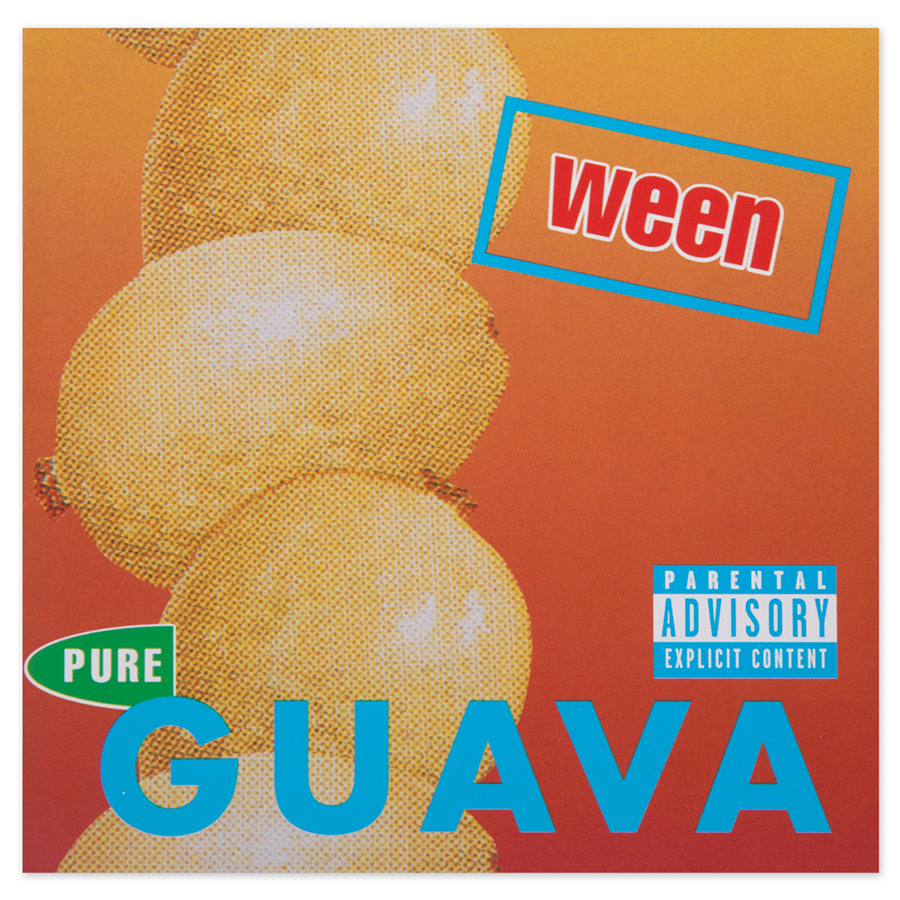

8 |Pure Guava (1992)

Featuring the band’s breakthrough hit, Pure Guava is a psychedelic album in a style that only Ween can do with songs that only these minds could have conceived.

Ostensibly a balance between the ideas founded on their first album and the whacked-out trip of their second album, Pure Guava is Ween at the peak of their lo-fi powers. Both visually and stylistically reminiscent of John Frusciante’s Smile from the Streets You Hold, Guava offers the most refined version of the band’s early sound before they jumped to the relative polish of Chocolate and Cheese.

Songs like “The Goin’ Gets Tough From The Getgo,” and “Reggaejunkiejew” play out like absurdist exercises in which the band is testing the edges of their own sanity by repeating a single sticky phrase over and over again atop an infectious groove. On the other end of these twisted experimentations are tracks that fly in the complete opposite direction stylistically, lyrically, and instrumentally. “Don’t Get 2 Close (2 My Fantasy)”is a soaring conceptual ballad in which the band volleys a non-stop barrage of unforgettable psychedelic imagery at the listener. All of these phrases culminate in a Bohemian-Rhapsody-like vocal break that shines forth unlike anything else in the band’s discography. It’s something so original and unique that it couldn’t thrive anywhere but this album.

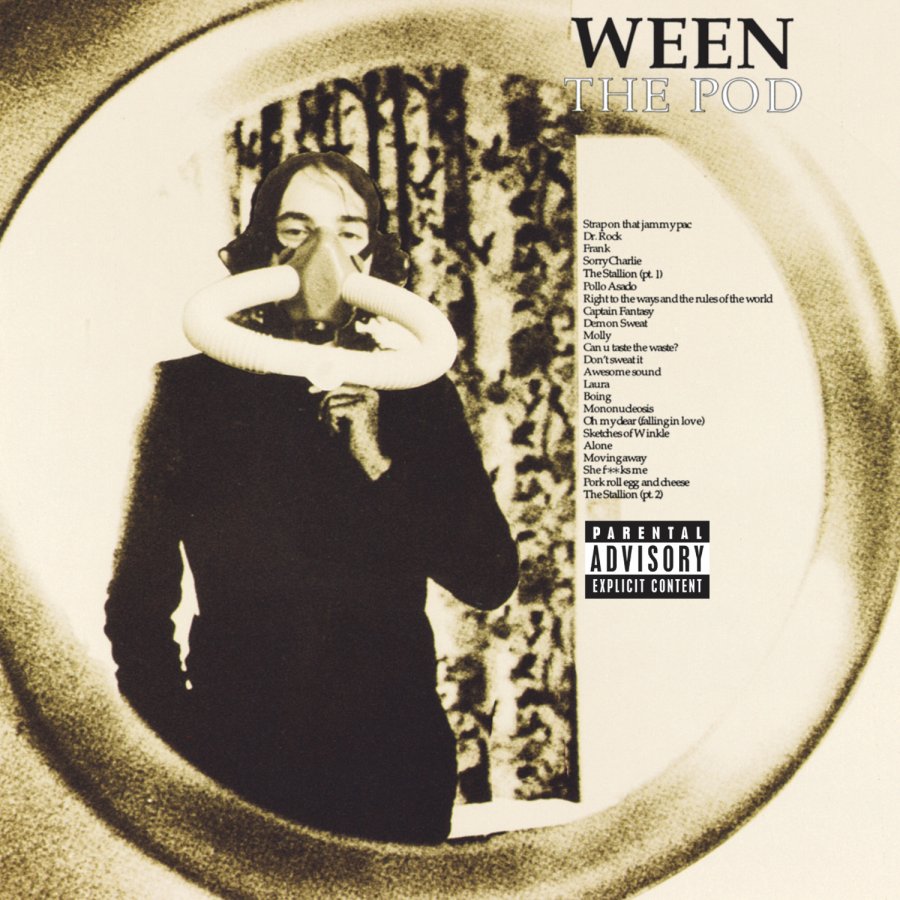

9 | The Pod (1991)

The Pod is Ween’s secluded, deranged, and drugged-out masterpiece that quickly reveals its brilliance to those willing to listen.

Even making it this far into Ween’s discography, you may still feel a palpable reaction of “what the fuck” when you first hit play on The Pod. Mutch like adjusting to the warm water of a hot tub, or learning to enjoy your first alcoholic beverage, The Pod comes with a brief adjustment period, but once it’s over, will be an experience you’ll remember forever.

Deeper and darker than anything else the band has ever recorded, it’s awe-inspiring how many impeccable melodies and brilliant ideas are hidden just one layer beneath a wall of practically-impenetrable sound. “Strap on that Jimmypac” is the opening curtain raise that attempts to acclimate the listener to the unique brand of narcotized journey they’re about to embark upon. From there each additional track throws the listener for a loop while also maintaining the same thematic range of strung-out haziness throughout. “Dr. Rock” is a punchy punky rock song. “Sorry Charlie” is a woozy saloon track that drips with regret. “Pollo Asado” is literally just a guy ordering Mexican food over muzak. It’s insanity.

Some of the most stellar tracks in the band’s discography come midway through the record in the form of “Captain Fantasy,” “Awesome Sound,” and “Demon Sweat.” These represent some of the most distorted, far out, and extreme lengths the band ever went to musically. Each song generally runs around 3-4 minutes, indicating a little more of a full-album approach than the sketchbook-like approach we saw on their debut.

The Pod is a true masterwork of a band without boundaries, traditions, or limits.

But Wait, There’s More

As much as I love Ween and these albums, this guide barely scratches the surface of the band’s output. There are B-side compilations, two EPs, several officially-released live albums, multiple different solo projects, demo sessions of most albums, radio recordings, and five of those early cassette releases. On top of all this, there’s Browntracker.net which hosts literally thousands of obsessively-made fan-created live recordings.

In short, there’s more Ween than you can shake a stick at, and if you wanted to, you could probably dedicate the rest of your life to listening to one of these a day and still not hear them all. But that’s one of the reasons that the band has such a dedicated fanbase, and it’s one of the things that makes being a Ween fan such a rewarding experience.

Finally

Ween revealed themselves to me at a pivotal time in my life. A time when I didn’t know what I wanted to do or who I wanted to be. A time when I was burnt out life, tired of music, and couldn’t find joy in anything. That was a soul-sapping and destructive feeling, and it’s crushing when it’s something you recognize but can’t shake.

The way that Ween balances abject silliness and utter sincerity felt like a cosmic revelation to me at the time. As I dug deeper into the group’s mythos and their music, Ween’s approach to the world came to influence my own. Simultaneously embracing absurdity and seriousness (or packaging one inside of the other) has been a comedic voice I’ve adopted for years at this point. As much as I love reveling in this bipartisan goofiness, recent events in the world have also given me a newfound appreciation for wholly genuine acts and real emotions. It was fun walking the “Ween line” where no one can quite tell which side of the fence you lie on, but it’s no longer my default approach to life as it was back then.

Aside from this newfound voice though, Ween’s discography along with John Frusciante’s PBX Funicular Intaglio Zone served as part of a one-two punch that year that reinforced and reignited my love of music. These albums blew the hinges off my preconceived notions surrounding art and single-handedly proved to me that there’s still room for untethered creative expansion in the world.

Ween helped remind me that the world is a beautiful place and it revealed to me that there are unheard and unfathomable ideas living within all of us. There are goofy lyrics and serious ballads. There are beautiful paintings and inspiring words. There are things that only you could ever think of, and these records serve as concrete proof that the only limits we place on ourselves are self-imposed.

There are beautiful, goofy, wonderful ideas inside your head that have never been heard, seen, or read before by anyone else. Concepts that, after millions of years, have never been conceived until you came along. And until we can unlock those ideas within ourselves, we might as well appreciate the sounds of others.