Poptimism, Complexity, and Musical Stockholm Syndrome: Why Some Albums Grow On Us Over Time and Others Don’t

/One of the biggest musical revelations of my life, like many things, came from a podcast. It wasn’t a cool song or the discovery of a new genre, but a conceptual framework that changed how I viewed the entirety of music.

The statement, born of a drunken video game discussion, found one of the hosts outlining his definition of pop music. His parameters weren’t based on the artist’s popularity or the sound of their music, but rather something that you could “hear once and enjoy.” He went on to elaborate “I didn’t even like most of my favorite albums the first time I heard them.”

I’m paraphrasing massively here (because I don’t remember the exact quote, episode, or even year), but this general notion is something that has stuck with me for almost a decade. It’s a bit of a roundabout way to define the pop genre (which I still love and appreciate), but it’s also a slightly snobby framework that looks down on an entire genre while simultaneously glorifying your own taste. So sure it’s problematic, but I also don’t think it’s entirely wrong. Pop music is scientifically designed to be catchy, appealing, and broad, that’s inherent in its DNA.

Still, the more I thought about this framing device, the more I found it to be true. I especially latched onto the host’s claim that most of his favorite albums were “growers” he found himself enjoying more over time. As I searched through my own music library, I realized that nearly all of my favorite albums were ones I’d listened to dozens of times and seemingly got better with each listen. In fact, most of them were records that I thought nothing of or flat-out dismissed at first but eventually grew to love. Oppositely, there were dozens of other albums (pop or otherwise) that I’d listened to once and forgotten almost instantly.

So this theory seemed to hold water, and it’s a filter that I’ve used to view music through for nearly a decade at this point. Recently the idea of albums being “growers” brought up online and spark quite a bit of debate. There’s one side that subscribes to the “grower versus shower” mentality, and another that views this behavior as simply subjecting yourself to an album over and over again until you like it. As with most everything, there’s truth to both sides and neither is truly “right.” So I’ve spent some time mulling over this framework, asking people about it, and gathering opinions from both sides of the fence. I’ve uncovered ten different inter-connected elements that are at play within the “grower” concept. I’m going to outline each point below along with personal examples in hopes that I arrive at some sort of conclusion or thesis statement in the process.

1) Denseness and Complexity

One of the biggest arguments in favor of returning to albums and the concept of “growers” is the idea that some genres/bands/records are so musically complex that they encourage it. Whether it’s lyrical, instrumental, or contextual, sometimes there is so much going on in a record that it’s impossible to take everything in on first listen. Take something like Pet Sounds or The Seer where at any given moment there are dozens of individual components all fighting for the same sonic landscape. You can listen to Pet Sounds once and “get it,” but repeated listens reward the listener by allowing them to slowly discover everything at play in these carefully-layered songs. It’s like crossing things off a list; once you know the lyrics you can pay less attention to the vocalist and focus on a different element of the arrangement. You can keep revising an album and delve deeper each time until you have the full picture; one that was impossible to see the first time you listened.

Meanwhile, pop music is almost always internationally bare. By remaining surface-level (both lyrically and instrumentally) pop songs are easier to grasp at first pass. This allows pop artists to more easily fulfill their primary purpose by transporting a single supremely-catchy hook or chorus into the listener’s brain. As a result, the pop genre as a whole actively avoids things that could “distract” the listener because those experimentations and imperfections are often things that risk detracting from the core message that’s being delivered. That’s not to say pop songs don’t require skill to make, just that they avoid anything too “out there.”

Take Katy Perry’s “California Gurls”: it’s a song that I adore, but I’ll be the first to admit there’s almost no substance to it. The main elements at play here are Katy Perry’s voice and a warm radiating synth line. There’s a guitar and bass laid underneath these primary elements along with a handful of ad-libs from both Mrs. Perry and Mr. Dogg, but those the closest thing to musical depth that this track offers. Much like the music video, “California Gurls” is a synthetic and sugary-sweet pop song that exists to convey a single straight-forward message. As a result, you have a song that’s catchy due in large part to the fact that it’s presented in a barebones way. By being lyrically or musically complex you risk immediacy, so you must present your song in a pointed way so as to embrace catchiness.

So obviously sheer mass and complexity are major factors in this debate. Some of my favorite records are indeed sprawling epics that I’ve essentially bonded with over the course of several years. Records that have drawn me back in time and time again and improved my impression of them in the process by developing a unique and ever-changing relationship with me. A musically-dense record will always be more rewarding to return to because it rewards repeated listens and allows the listener to pick up on something new each time. Meanwhile, a pop track may keep a listener coming back for the earworm factor, but won’t necessarily be as deeply rewarding the same way that a “complex” album would be.

2) The Unknown Factor

Sometimes there’s a mysterious, unknowable X-factor that keeps you coming back to a record. Even an album you don’t like can draw you back, if only to pin down its ephemeral magnetism. This has happened to me in 2012 with Carly Rae Jepsen’s megahit “Call Me Maybe” and (after dozens of listens) I’ve since pinned it down to her unique delivery of the goosebump-inducing line “and.. all the other boys.” Early on in his excellent 150-page CRJ-based manifesto, Max Landis does an excellent job of breaking down the song’s undercurrent of distress and subversion, but the point is in 2012 we, as a society, were collectively drawn to this song for some reason.

Sometimes it’s as simple as a weird vocal quirk, other times it’s an attention-grabbing instrumental moment, or a riff that gets stuck in your brain like jelly. In any case, these unique moments aren’t limited to one genre and their ear-worminess plays a huge part in why we return to a piece of art.

I’ve done this with countless songs. Sometimes I’ll find myself listening to an entire album just to experience a single moment in full effect. Sure I can listen to Hamilton’s “Take a Break” in isolation, but it’s only when I listen to the entire play from the beginning that I fully tear up at the song’s implication within the larger narrative. Moments in the song like hearing Phillip’s rap, coupled with Alexander’s growing distance from his family, and dark multi-leveled foreshadowing, are all made more impactful when the piece is taken in as a whole. We don’t get to pick the little things that draw us in, but this search is one of the most rewarding aspects of music appreciation and discovery.

In a third case (I’ll fully-delve into deeper this December), up until last year, Sufjan Stevens has been an artist that I wanted get into. Thanks to a serendipitous iTunes DJ Shuffle back in high school, I became infatuated with exactly three of his songs and I spent literal years listening only to these three tracks until I was ready to explore the rest of his discography.

The Carly Rae Jepsen example proves that there’s still room for these moments in a pop song. Experimentation and subverting expectations can reward the artist in unexpected ways, but if there’s not something there to make the listener curious enough, then it’s unlikely that they’re going to go back and try to figure it out on their own.

3) Critical Acclaim, Message Boards, and Peer Pressure

Like it or not, critics play a role in dictating taste within culture. I suppose it’s less like “dictating” and more like influencing, but I think we’ve all been swayed by reviews at one time or another. Whether it was being convinced to stay away from a bad movie, or giving a record a spin based purely on universal acclaim, critics have an undeniable impact on our cultural landscape.

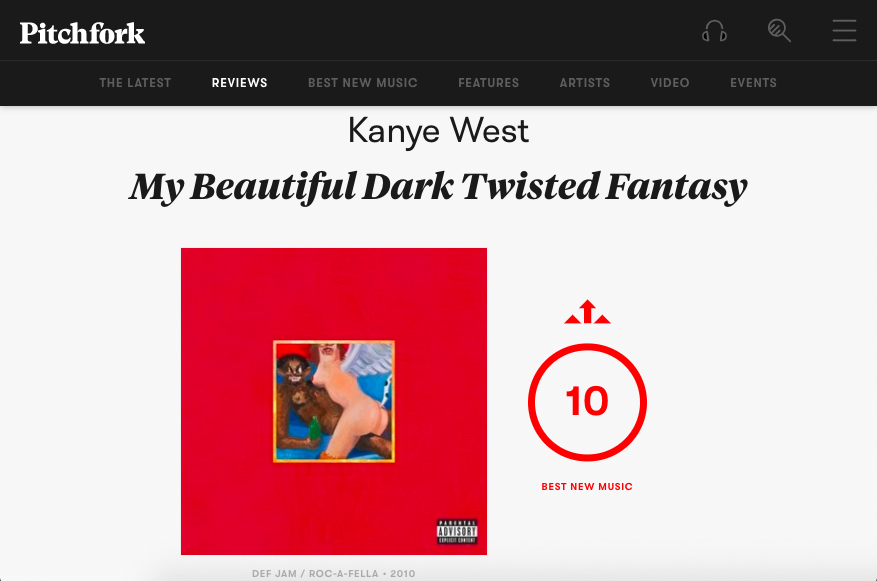

I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. At worst it will make you more hesitant, and at best you might give something a chance that you never would have known about otherwise. I did this with Kanye West in 2010 following the release of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, after its perfect Pitchfork score and placement as their best album of 2010. Aside from Eminem, I’d never really listened to any hip-hop in earnest, but this level of praise couldn’t be a coincidence, right? I downloaded the album, gave it a reluctant spin, and came away from it mostly underwhelmed.

As a side note (before I get called out) it’s worth noting that I didn’t have any context for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy at the time. I had no idea about Kanye’s background, or what the album represented within his career. I also had no real appreciation for the record’s layers upon first listen (circling back to Point #1) but I went on to rediscover and genuinely love it in 2016. The point is I picked up this album solely because of critics.

Continuing the Kanye West anecdotes; I’ve already written about how the internet’s reaction to the release of Yeezus spurred me to give the album a shot. I still didn’t get him. For whatever reason, I gave the album another listen a couple months after its release and suddenly everything clicked. I loved Yeezus and soon found myself venturing back through Kanye’s discography from the beginning. I’d like to think that I came to love Kanye of my own free will, but the reason I gave him a chance in the first place (and the second place) is because of other people. Whether it was a “reputable” journalistic source like Pitchfork, or simply witnessing the unbridled joy of hip-hop heads on an internet message board, I could tell I was missing out on something, and that kept me open.

4) Personal Context, The Language of Genres, and The Passage of Time

After “discovering” Kanye West in 2013, he was the sole hip-hop artist I listened to for some time. I would casually browse forums and keep up on large-scale movements within the genre, but it wasn’t until years later that I would find myself delving deeper into the contemporary rap scene. By the end of 2015, I was listening to everything from leaned-out trap, conceptual double albums, absurdist mixtapes and even Drake. Soon I found myself listening to goofier (then) lesser-known acts like Lil Yachty, Lil Uzi Vert, and Desiigner. I can guarantee you that I never would have latched onto any of those guys if it wasn’t for Kanye breaking down my personal barriers and dismantling my hip-hop-related hangups. It took time for me to go from actively disliking hip-hop to embracing it wholeheartedly, and that’s a journey that can only happen over time.

While your personal journey within individual genres matters, there are also things like general knowledge and maturity at play too. Once I got out of that shitty high school ‘everything that’s popular sucks’ punk mentality I opened myself up to dozens of new artistic directions. I gained a new appreciation for things I’d previously despised, and I began to understand why things like MBDTF were important. It’s a combination of open-mindedness and cultural awareness that comes with age, and one that I hope never slows as I get older.

Maturity is an uncontrollable factor that’s hard to pin down, and impossible to quantify. I’ve experienced “musical maturity” as recently as this year with the Fleet Foxes. They were a member of my generation’s pivotal “indie folk movement” and I consider them one of my gateway groups, but despite their importance, I’d never really considered myself a fan. And it’s not for lack of trying, I own all their albums, gave them multiple chances throughout high school and college, but I had always found them interminably boring. I didn’t see what other people saw in them… until this year. With the multi-month build-up to 2017’s Crack-Up, I found myself giving into the hype and giving their older albums another shot for the first time in years. To my surprise, after a handful of half-passive listens I really liked everything I heard. All three of their previous releases grew on me over the course of several weeks, and I became a fan like that. I can still see why I found them boring in high school, but I think the real reason is a lack of maturity. I now have the patience and appreciation for the kind of careful, measured indie folk they’re making, and that openness has rewarded me with hours of enjoyment.

Circling back to Point #1: it’s often hard to fully grasp an album on first listen, and sometimes a record’s complexity doesn’t allow it to truly grab ahold of you until years down the line. In a way, this is also a point against pop music since so much of it “of the moment” it tends to age worse. It’s a genre that’s by nature the most tapped into pop culture, and as a result, it’s harder to go back and enjoy older songs when A) you’ve heard them thousands of times, and B) there’s more recent stuff that’s more tapped into the current sound. It feels like there’s more of an “expiration” to pop music which means it’s not necessarily as rewarding to venture back to.

5) Streaming, Permanence, and Getting Your Money’s Worth

A semi-recent extra-musical factor at play in this discussion has to do with how we consume music. Up until about a decade ago the process was 1) hear a song 2) go buy the album at the store 3) listen to the album. With the rise of iTunes, YouTube, and more recently, digital streaming platforms the entire process has become flattened. A song can come to mind, and we can pull it up on our phones within 30 seconds. You can hear a song at a bar, Shazam it, and add it to your digital collection within an instant.

As a result of this, albums as a concept have been diminished in both stature and importance. You have people like Chance The Rapper releasing retail mixtapes, Kanye West updating his albums after release, and Drake releasing commercial playlists. But on top of these (somewhat arbitrary) distinctions, there’s a layer of increasingly-pervasive accessibility. You can hear about an artist and have their discography at your fingertips within seconds. You can read about a new release and be streaming it by the time that it takes you to finish this sentence. That freedom has forever changed how we consume music. Comparing this on-demand accessibility with the “old ways” of going to a store and buying a physical record, it’s easy to see how the times have changed.

As a result of this shift, people are less committed to albums. If you don’t like an album you can play another just as quickly. We can jump ship with no loss at all. We’re not connected to the record, so it’s easy to abandon.

Funny enough, with the rise of streaming we’ve seen a near-direct correlation with the rise in the popularity of vinyl as it’s on track to be a billion-dollar industry this year. These are people that want and miss that physical connection with their records. There’s an undeniable difference between listening to an album on Spotify and hearing it come out of your vinyl player at home. “Warmth” and all that bullshit aside, this is an example of the format influencing our listening habits. If you’re using Spotify and don’t like an album, you can easily stop streaming and jump to any of the millions of readily-available alternatives.

Most importantly, when streaming, there’s also no reason to “justify” your purchase because we haven’t dropped $20+ on a piece of physical media. If you bought a record and didn’t like you’d damn sure try to listen to it more than a few times because you invested in it, goddammit!

There’s also a pattern of familiarity at play too. Every time you open Spotify you’re given the choice between something new and something that you already like. If you gave an album a shot and didn’t like it, you’re now given a choice between that and something you know you already like. So why would you ever opt for the thing you don’t like?

Reddit user nohoperadio explains this phenomenon and the wealth of choices that we have in the modern music landscape:

“Those pragmatic constraints on our listening habits don’t exist, and we have to make conscious decisions about how much time we want to devote to exploring new stuff and how much time we want to devote to digging deeper into stuff we’ve already heard, but every time you do one of those you have this anxious feeling like maybe you should be doing the other. It’s only in this new context that it’s possible to worry that you’re listening wrong.”

It really is an interesting psychological door that’s opened with our newfound technological access, and analysis paralysis aside, it explains why some songs draw listeners back by the millions. Drake’s “One Dance” is the most streamed Spotify song of all time with 1,330 million plays. It’s a good song, but not that good. It’s an example of a song achieving a balance of accessibility and pervasiveness until it becomes habitual and self-reinforcing. That’s something that only could have happened in the streaming world.

6) Fandom

Up until now, we’ve mostly been talking about this framework within the context of “new” albums, but what about when you already have context? What about a non-accessible release from your favorite artist?

This has happened to me with many albums over the years. I wrote a 7,000-word four-part essay that was mostly just me grappling with my own disappointment of Drake and Travis Scott’s 2016 releases. For the sake of talking about something new: The Wonder Years are one of my all-time favorite bands. I’ve written a loving review of their second album, and I plan on doing the same thing with their third and fourth releases as well. After a trio of impactful, nearly-perfect pop-punk records, the band released their fifth album No Closer to Heaven on September 4th of 2015. While it’s not an “inaccessible” record, it’s easily my least favorite from the band and a far cry from their previous heart-on-sleeve realist pop-punk. It took me months of listening to the album to fully-realize my disappointment, and even longer to figure out why. I’m still not sure I can accurately explain why Heaven doesn’t gel with me, but that’s not what this post is for. The point is I’ve subjected myself to this album dozens of times racking up nearly 700 plays at the time of this writing. In fact, it’s my 19th most-listened-to album of all time according to Last.fm, and that’s for an album that I don’t even enjoy that much!

I was driven to this album partly by my frustration and confusion, but also my love of the band. I’ve enjoyed literally every other piece of music they’ve ever recorded, what made this one so different? I guess 700 plays isn’t something you’d afford even the most promising album, but this is an example of the listener’s history influencing their own behavior and desire to love an album. It’s trying to make an album into a “grower” when it may never be one in the first place. That leads nicely into #7…

7) Instant Gratification, Uncertainty Tolerance, and “Forcing It”

The most common argument I see against the concept of albums as growers is the idea that the listener is “forcing it.” This is problematic mainly because everyone’s definition of “forcing it” is different. Some people have a specific number in mind ‘if you listen to an album three times and don’t like it, then you’re forcing yourself’ others base it on feeling ‘if you’re despising every second of an album, then just turn it off. Otherwise, you’re forcing it.’

The idea is you force yourself to like something out of pure habit or by subjecting yourself to it over and over again, eventually becoming hostage to something that you didn’t really like in the first place. To me, this is the meatiest discussion point here because it’s such a multifaceted issue. I’ve already discussed this concept within the context of Drake’s Views, but to briefly recap: I loved his 2015 album If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, and he had a killer summer with What A Time To Be Alive and a high-profile rap beef. I was beyond hyped for his next release in 2016 but came out of my first listen incredibly disappointed. Over time I grew to like most of the songs, presumably from sheer repetition, but I still recognize it as an album that isn’t good on an objective artistic level. So is this forcing it? I never hated any of those listens, I just grew to like the album more after time had passed, but I still don’t think it’s good.

I’ve done the same thing this year with Father John Misty’s Pure Comedy. After an impeccable 2015 release and a metamonths-longinterview-ladenlead-up to the record’s release in April I, again, emerged from my first listen disappointed. I have come to enjoy the album more over time, especially after giving myself a break from it and seeing some of the songs performed live. So maybe these two cases just have to do with unrealistic built-up expectations and already being a fan (Point #6) but no matter how you look at it, I wanted to like these albums and kept subjecting myself to them.

At any rate, the biggest flaw with this argument is that everyone’s definition of “forcing it” is different. Unless someone’s making you listen at gunpoint, there is no force. You can stop at any time and you shouldn’t feel pressure to like something just because. But I fully recognize someone could see my listening history with Drake’s Views and say “my god, why would you listen to an album you’re lukewarm on that many times? That’s torture!” but I guess what’s torture for some is simply passive listening for another.

For a more scientific perspective, this youtube video details some of the crazy behind-the-scenes factors at play in making pop music particularly pervasive. Everything from the radio to Urban Outfitters to fucking memes spread music and have the ability to make something exponentially more popular. This circles back to “forcing it” because you may have no power in these cases. God knows after years of the same retail job I grew to hate some songs that were otherwise great just from sheer repetition. It would make sense that this then becomes “forcing it” since you have no power, but sometimes even that can circle back to genuine love if you build enough positive associations over time. I may not like “Hotline Bling” as a song, but god knows I’ve upvoted enough memes featuring the turtleneck-clad Drake that I enjoy something about it.

Furthering the pseudo-scientifical discussion of articles I that don’t have the intelligence to write of research: this blog (which cites this study) discusses “addiction economy” and explores the profiles of “explorers” and “exploiters.” The primary difference between the two groups is their propensity for either delayed or instant gratification. The study explores the idea that technology has accelerated this process which (in a music context) circles back to Point #5 of streaming’s role in our listening habits. Why bother trying to listen to something “difficult” or “weird” when you can have the instant hit of euphoria that comes with a bouncy non-offensive Taylor Swift song?

I really think this one comes down to what you’re in the mood for. If you have the attention, time, and necessary background, why not explore something rich that you may love? But if you just want something quick and easy, just put on the Spotify Top 50 for some background noise. It becomes the musical equivalent of a hearty homecooked meal versus a big, greasy fast food burger. One may be objectively “better,” but it’s not always right for the situation.

8) Expectations and The Initial Approach

Another factor that exists outside of the music itself is the listener’s initial approach. If you go into any art with a preconceived notion you’ll either be surprised by the outcome or have your beliefs confirmed. If you go to a shitty movie expecting it to be shitty, you’ll emerge thinking “well duh.” The inverse of this could also be true (a shitty movie turning out good, etc.), but the real discussion here has to do with the viewer’s initial expectation.

I do think with music it’s rare that you’ll do a complete 180 in either direction. The most likely case of a “grower” is generally a record that you go into not knowing anything about and then some unknown factor (Point #2) keeps bringing you back. It’s also true that you could dislike and album and over time come out liking it (as I did with Views). And while it’s a rare occurrence, I suppose an album could also be a “shrinker” that you love on first listen, but grow to dislike more and more.

Circling back to genres, I think pop music tends to be a shrinker more often than not. It’s something that’s (by nature) immediately accessible but slowly drives you mad with each repeated listen like a screw tightening into your skull. We’ve all been there (especially anyone with a retail job) but I can’t think of a single occurrence where I’ve done that to myself of my own free will. Oppositely, I know people that only interact with music by listening to songs until they’re absolutely sick of them. That’s not how I prefer to interact with art mainly because I feel like there’s only so much time in the day and so many other things to listen to, why force that upon yourself?

I think that the listener’s starting point is a huge concept. Reddit user InSearchOfGoodPun outlines his thoughts on the initial approach and the impact of time on your listening experience:

“My personal opinion is that if you listen to almost anything enough times with a receptive attitude, you will start to appreciate it. It might not become one of your favorites, but you’ll like it for what it is. In any case, at the end of the day, you like what you like.”

The key phrase here is receptive attitude. If you aren’t listening with a receptive attitude, then you’re forcing yourself. Then you’re just making it unenjoyable no matter what. I think this is one of the biggest points in this whole write-up and a key indicator of who you are as a consumer of art. It’s all about being receptive regardless of your starting point.

9) The Language of Genres

Jumping back to Kanye: it was a long and winding road filled with lots of resistance, but despite my own hangups, I now consider myself a hip-hop head. I listen to the genre constantly, I’m up on the “newcomers” and I find myself devoting an absurd amount of time to researching the realm’s happenings each day. I wouldn’t have cared that much without Kanye, and I wouldn’t have discovered half of the shit that I currently love without Yeezus breaking those barriers down.

I’ve spent this entire time talking about albums as “growers,” but it’s also possible that this concept could be applied to entire genres too. I mean, after all, a genre really is like a language you have to learn, and I was fortunate enough to have Kanye as my teacher. Through his discography, I learned about the genre’s history, who its major players are, as well as the language, cadence, and frameworks that it uses. In another sense, it’s almost like “building up your tolerance” to something you previously didn’t understand or couldn’t grasp.

I’ve detailed my own history wading into genres like hip-hop and indie, but it makes sense that this personal context would impact how we would interact with albums through the broader umbrella of their genre. I wouldn’t have understood hip-hop if I jumped straight to Migos. Everyone has a starting point for their musical taste, and it spreads outward from there. Pop music is an easily-accessible taste, but most other genres take a little bit more of an adjustment to get used to. Certain albums or genres are just objectively less-accessible, and harder to get into as a result.

In fact, it could easily be argued that exploring a genre could be the biggest decider on whether an album is a “grower” or not. Contextualizing a record within a larger space can help the listener and understanding it better and appreciate it more. Listening to one album multiple times might be the exact opposite of the correct approach, because while the listener may not like it, they may find something musically adjacent that’s more up their alley.

10) Songs Versus Albums

For the sake of furthering the discussion outside of albums, it’s also worth zooming down to a micro level to look at individual songs. While I tend to listen (and think of things) in terms of albums, it’s undeniable that songs are the main component at play. In fact, a single song is probably the reason for you checking an album out in the first place. Thinking “hey I like this one thing, maybe I should check out the rest” is how I’ve discovered most of the music in my library.

But this same framework of “growers” can easily be applied to songs too. When listening to an album the first time, occasionally only individual songs will jump out at you right away. I love Lost in the Dream by The War on Drugs, but for the first dozen or so times I played the album, the only song I could remember was the opener “Under the Pressure.” That song had a memorable chorus, a catchy riff, and a driving rhythm. It alone is the sole reason I kept coming back to the record, but each time I put “Under the Pressure” on I’d find myself thinking ‘ah, I’ll just let the rest of the album play.’ Eventually, the rest of the record revealed itself to me and individual songs emerged from what was once an amorphous blob of sun-drenched heartland rock.

I did the exact same thing with Young Thug’s breakthrough 2015 album Barter 6. I’d already had a passing interest in Thug thanks to his previous collaborative efforts with Rich Homie Quan, so I gave Barter a semi-attentive spin and left underwhelmed. After a glowing Pitchfork review (Point #3) I gave the album another shot but couldn’t find myself getting past the first track. In a good way. I kept relistening to the album opener “Constantly Hating” and every time I tried to move onto something else, this transfixing opener drew me back in. Soon Barter 6’s second track grabbed me just as hard. Then the third. Then a single. Then a late album track. Eventually, I was listening to the whole thing front-to-back and enjoying every song. Individual songs are a viable path to an album becoming a grower, and while I don’t like digesting albums piecemeal, sometimes that approach can allow an album to creep up on you over time.

Final Thoughts

At the end of the day, there’s a difference between feeling lukewarm on an album then giving it a few more chances and hating an album but feeling like you’re obligated to listen because you “should” like it. Usually, there’s some redeeming quality that brings you back, God knows there’s plenty of albums I’ve heard once then forgotten forever.

Patience is key, and that receptivity can lead to an album becoming better over time. With pop music, I feel like there’s an individual tipping point that everyone hits where you go from fully-embracing a song to actively combatting it. We don’t all have the time or patience to devote ourselves to “difficult” albums, so sometimes the road less traveled is less appealing.

After writing all of this, I’ve come to the conclusion that my initial theory is a flawed. Like many things, it’s not universal. There’s no one “right” answer or perfect framework that applies to all of music. This theory still works on a case-by-case basis, but there’s nuance to every genre, artist, and song, and this broadness makes it hard to view music through such a broad lens.

If anything, a big takeaway is that there’s no one “better” genre, just different fits for different people. With all these possible elements at play, it’s easier to see how someone could gravitate towards one easier genre meanwhile a different person has cut their teeth in a different genre and has a more developed understanding of its intricacies.

And whether you look at it as “a grower” that gets better over time or a “shrinker” that driver you more insane with each listen, there is a point at which you are “forcing it” but (again) that varies from person to person. The only absolute is that there are no absolutes.

The truly compelling part of music is the way that you interact with it. What you bring to the experience and how you interpret the artist’s work. Whether it’s going track-by-track or listening front-to-back, or listening to one single song until you’re sick of it. Music is special because of what we project onto it. The memories we make around it.

It’s obviously incorrect to view all pop music as shallow, just as it’s incorrect to view all rock as deep, or all rap as thuggish. Everything is on a spectrum, and your perspective within the genre, the artist, your life, and the world all come into play when listening.

I don’t think there’s any defined “conclusion” to arrive at, just many different elements to keep track of. These frameworks can help explain why I like A while you like B. The absolute most important thing to take away from this is to keep an open and receptive mind.

I’ve recently come to the realization that my dream job, the one thing I really want to do, is to share things that I love with other people. To spread art, joy, and love in hopes that someone else is affected by these things the same way that I am.

That requires an objective mind, but you still won’t ever like everything. And that’s okay. You shouldn’t have to.

I think sharing things and spreading love is productive for the world.

It’s the most positive impact we can make on the world around us.

It’s spreading beauty.

Both being able to see why someone likes something and being able to share your own experience. It’s the one universal. The human experience. We all have unique perspectives, thoughts, and lives. Sometimes sharing is the only thing we can do.

Art is a bonding agent.

What we add to it is the special part.

Remain open.

Share your love.