Ben Quad – Wisher | Album Review

/Pure Noise Records

Ben Quad are back. Not only are they back, but they’re fucking huge. Or at least that's what it feels like for those of us in the emo world, anyway.

I first discovered Ben Quad because I was endeared by the idea of a new band using so many interesting tricks and flips from the same dust I grew up in. They’re one of several Oklahoma acts from the past several years to break out of their local scene to more renowned heights, alongside acts like CLIFFDIVER, Chat Pile, and Red Sun. What makes Oklahoma such an outpost for this style of music? I am not quite sure, but earlier this year, I was in Ben Quad’s home state for a couple of concerts. Both nights, I stood outside my hotel room, looking at the way the sky never ends there. If I grew up under that sky, I would try to absorb the world with my guitars, too.

Wisher is technically Ben Quad’s sophomore album. But between 2022’s I'm Scared That’s All There Is and present day, the band has unleashed a steady flow of releases that tightened their sound and expanded their ambitions. First, they released “You’re Part of It,” a standalone screamo single that felt like an instant addition to the Emo Canon. Then there was Hand Signals, a tour split, and finally Ephemera, their 2024 post-hardcore EP where they cited groups like Underoath and Norma Jean as inspiration. Wisher elaborates on the Ben Quad that Ephemera left behind, offering something not quite as genre-hopping but upholding that harsher sonic twist with even more experimentation.

Ben Quad have described their new album as “post-emo,” a kind of theoretical subgenre that I’ve heard described as “emo but better” or “not real” depending on who you ask. Whatever it is, it marks a departure from the rules of the original emo sound and a step further into the depths of rock.

Wisher is an album that spans the parking lots of Warped Tour metalcore, the terrain of midwest emo, and the highs of country lilts, all with dizzying guitar tapping, frenzied screaming, and a desperate demand for something better than this. The record is full of “what-ifs,” both sonically and lyrically. What if we dialed this amp to eleven? What if we added tooth-grinding bass here? What if I told them I’m sorry? What if they told me they’re sorry? Say you’re sorry, you’ve been so hard on me. You. You. You.

The album begins with a banjo’s twang on “What Fer,” floating over the atmosphere that Ben Quad are desperately trying to find the limits of. The instrument bends with the breeze before ripping into the sky with electric guitars playing so ferociously you worry they might summon a lightning strike. The energy they build here shocks everything directly into “Painless” where Sam Wegrzynski begs some faceless other to “please just tell me how you’re doing” while Edgar Viveros’ guitar arcs around the song.

It’s at this point that I realized this album is so big that I had to talk to them about it.

Swim Into The Sound: This album sounds massive. As a long-time Ben Quad listener, I have always appreciated how flexible y’all are in your sound, but this is the biggest the band has sounded yet. I know you spoke a bit about the expansive studio access inspiring some of the sound, but what about the scale?

Edgar Viveros: A lot of that has to do with Jon Markson’s magic. We really wanted to go with someone who could have a major impact on the production of the record. We walked into that studio with the intention of writing bigger choruses, and he knew exactly how to make them sound massive. We had so many new direct influences on the record, too — country, electronic, pop-rock. We knew early on that we wanted to have songs that got as big as a Third Eye Blind, Goo Goo Dolls, or Killers track.

No matter whether the band was tapping out Midwest Emo, post-hardcore, or playing along to an Always Sunny clip, Viveros’ guitar playing has always been a beloved aspect of Ben Quad. His style is very distinct in this era of post-emo: irrevocably fast, intricate, and loud. During live shows, Viveros stands center stage, radiant, as the crowd screams at him to play forever. On Wisher, he does seem to play forever, each song demanding something new and exciting, like the ethereal reverberations of “Classic Case of Guy on the Ground” or the world-absorbing work on the closer, “I Hate Cursive and I Hate All of You.”

SWIM: I personally hear a lot of the stuff I grew up with — third and fourth wave emo, 2010s metalcore. What music were you inspired by while recording this album? What was it like working with Jon Markson?

VIVEROS: This record was influenced by so many things that I know I’ll probably forget something. The 3rd and 4th wave influence is definitely there. We’re all big fans of stuff like Taking Back Sunday, The All-American Rejects, and Motion City Soundtrack, and I don’t think there’ll ever be a Ben Quad record where my guitar playing won’t be inspired by Algernon Cadwallader and CSTVT. Stuff like Brakence and Porter Robinson heavily inspired the glitched-up guitar samples that are all over the record. There’s a good amount of banjo and slide guitar that draws inspiration from country and folk music. Personally, the recent wave of alt-country, like MJ Lenderman, really inspired me to dive into that style of playing. Beyond that, there’s huge Third Eye Blind and late 90s/early 2000s pop-rock influence.

When it comes down to it, a lot of this record was us channeling the sounds we loved growing up to make something new. Jon Markson helped out so much with making that vision come together. His perspective was such a valuable resource when we were finalizing songs, and I don’t think I’ve ever worked with anyone who has pushed me to be a better musician as much as he did. It was such a cool experience to wake up and record music all day with him for three weeks. That guy rules. I look forward to being isolated on a farm with him many, many more times.

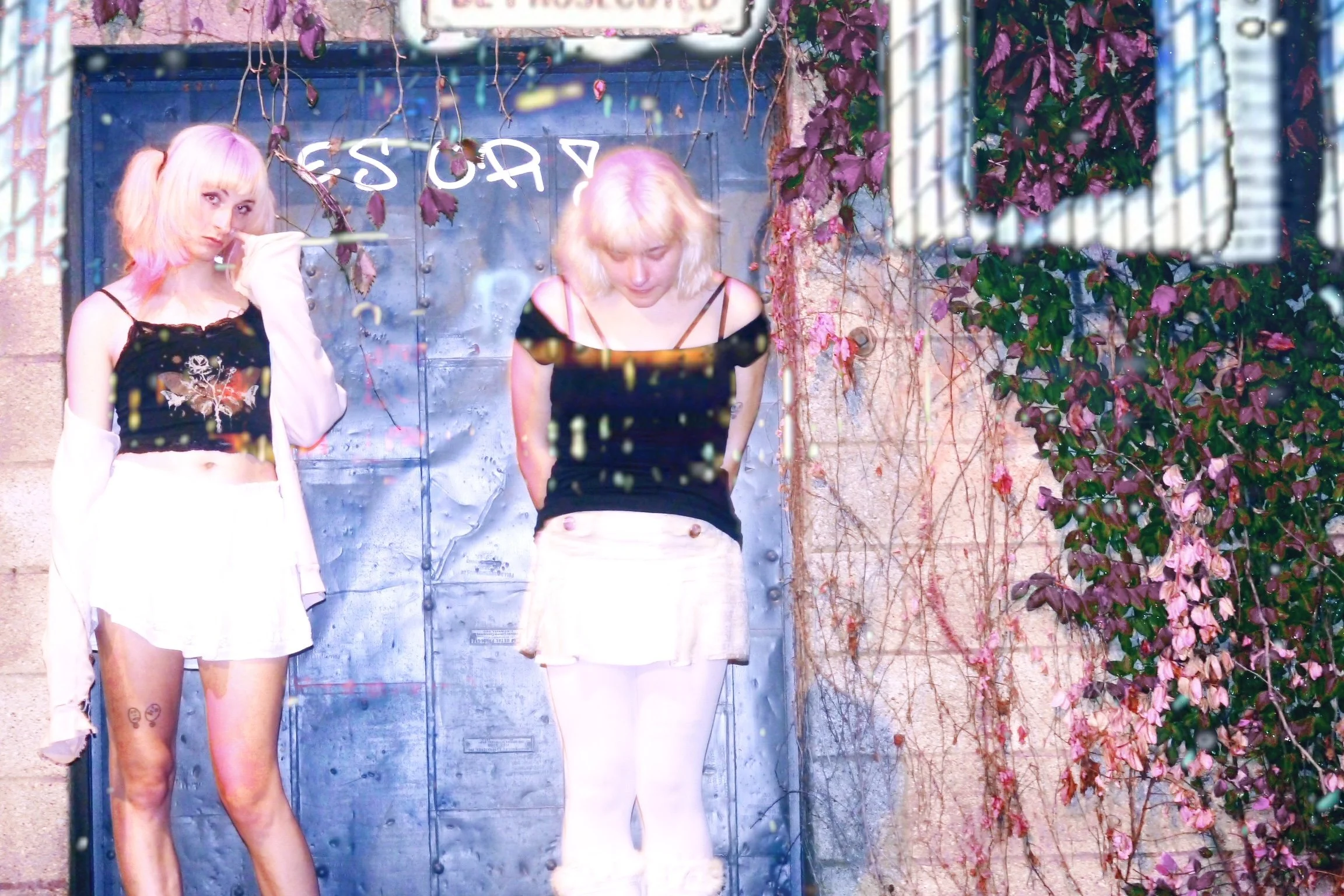

Photo by Kamdyn Coker

There’s a chance that this album might launch a dozen tweets about Ben Quad not being emo anymore from whatever the remnants of DIY Twitter are posting these days, but know that there’s nothing people can say that Ben Quad doesn’t already know. They make this abundantly clear on “Did You Decide to Skip Arts and Crafts?” with Sam Canty from Treaty Oak Revival.

SWIM: I’ve always heard that Oklahoma sound in your music, but never as much as I hear it in “Did You Decide to Skip Arts and Crafts.” What inspired y’all to bring a country twang to such a loud emo song? Do you see a connection between country and emo?

VIVEROS: I demoed out the instrumentals for that song in the summer of 2024 and really didn’t know where to take it. I kind of just wrote the song structure to be a mixture of big, anthemic Wonder Years choruses and some of the twangier moments in the Beths’ catalogue. It really came together when we invited our friend Sam Canty to hop on the track. That’s when I think we decided to really lean on the arena country-rock sound. I specifically love how Rocklahoma-coded the bridge sounds. Sam Canty’s feature fits so perfectly. I think the link between the two is a lot closer than people think. Sonically, both genres incorporate sparkly single coil guitars, and they both get pretty sad. Country is just farm emo.

I agree with all of the above: the connection between country and emo is storied, they’re both wrought, misunderstood genres that come from the middle of our nation. The aforementioned track starts with a phone call from Canty, playing a detractor of Ben Quad’s ever-evolving sound, telling them that they “ain’t the same anymore.” The song kicks in, and eventually Ben Quad gets him to change his mind and his sound too. Isaac Young clears a space in his drumming for Canty to return to the song to yell too, his Texas accent curving around an exasperated, “I guess it never made a fuckin’ difference to you.”

It’s impossible to discuss this album without acknowledging just how many people are on it; in addition to the Treaty Oak Revival frontman’s appearance, Zayna Youssef from Sweet Pill joins Wegrzynski and Henry Shields to kick your teeth in on “You Wanted Us, You Got Us.” Later on, “West of West” features Nate Hardy of Microwave, who contributes what might be the heaviest moment on the entire LP. It all starts to feel like a totally deserved victory lap, a testament to how big emo (or post-emo) has grown over the past few years, and a reminder of how much Ben Quad has grown since they met each other on a Craigslist post over their love of Microwave and Modern Baseball.

SWIM: Y’all have called this album a kind of evolution for Ben Quad. How would you describe Ben Quad’s evolution since I’m Scared That’s All There Is, sonically? Since that album, y’all have also toured pretty nonstop (I think I’ve seen you guys three or four times on different tours over the past few years) – How would you describe Ben Quad’s evolution since your debut beyond the sound? Any ideas on what’s next after Wisher?

VIVEROS: I’m Scared That’s All There Is was cool because it was basically us doing emo revival worship with a little bit of a modern twist. Since then, we’ve just been throwing more and more influences into the kettle. I love that you can trace through our discography and see us gradually adding influences of screamo and post-hardcore. This new stuff has country, electronic, pop, and so much more thrown into the mix, and I’m just excited to keep growing that sound moving forward.

Beyond sound though, I think we’ve grown in a lot of ways since the ISTATI days. We’re way more road-worn. When we released ISTATI, we hadn’t actually done a proper tour. Now, we’re releasing this new record on like our sixth full US tour. That alone has given us so much perspective on the world and many chances to meet a lot of talented and insightful people. I’d say our biggest area of progression has been in the confidence of our songwriting abilities. We’ve put out a handful of releases at this point, so sitting down and writing songs just feels so natural now. We’ve learned to just go with our gut when it comes to making music. I think any writing roadblock we encountered during the recording process was sheerly because we were afraid of sounding too honest or vulnerable.

At the end of the day, if we think it sounds good, then that’s all that matters. As far as what’s next after Wisher, I have no idea. Maybe we’ll make a real butt-rock record. Some real Breaking Benjamin type shit.

Anything is possible when it comes to Ben Quad. At its heart, that’s what Wisher is about: testing how far post-emo can stretch, showing off the possibilities of the sounds they can craft, and clearing a path for what’s next. On Wisher, Ben Quad ain’t the fucking same anymore, but who would want them to be?

Around this time, three years ago, Ben Quad released “You’re Part of It,” where they chanted endlessly and heart-wrenchingly about how they were just waiting for all of this to fall apart. Unfortunately, with Wisher, they’re just going to have to keep waiting, because this album is universe-engulfing and none of this is falling apart.

Caro Alt (she/her) is from New Orleans, Louisiana, and if she could be anyone in The Simpsons, she would be Milhouse.