How did the throughline concept for Happy Again come about?

I was doing my internship for college at a grief support organization. They were having me format and check these grief fact sheets that focused on different topics. I read some of them when I was bored. I came across one about spousal death, and it said something about how being happy after their death is possible, even if things are different. I started thinking about my own life at the time. I was going through a rough patch and I was kind of homeless. I wrote down “it’s not that you won’t be happy again, you just won’t be the same as you were before.” And it just felt right to revolve all of the songs around that concept.

What are some of the biggest influences for your upcoming full-length, and what has changed since the EPs?

The only emo I really listen to at this point comes from bands I’m friends with. Charmer and Origami Angel are two of my favs, and I think I learned a lot from each band about songwriting. Both can make really simple things sound beautiful and really complex things sound intuitive which has impacted my writing I think.

Otherwise I listen to a lot of pop/singer-songwriter music that has influenced how I approach lyrics and melodies. Our new songs are definitely still super riffy, but what has changed a lot is the approach to making sure the whole song is good rather than just having a cool riff. I want anybody to be able to hear a Stars song and like it, not just Midwest emo kids.

Your album covers, merch, and tour art feel like they all perfectly encapsulate the sound and feel of your music, how did your relationship with Alexis Politz begin?

Thank you! Alexis is the literal best. She was recommended to us by a friend from Minneapolis when we were looking for artists in 2015. She designed our first EP artwork and a couple of shirts and it just clicked. It felt like everything she created fit our music so well. She just kept getting better, and by the time we recorded Happy Again, it was a no brainer. I definitely want her to do our full-length art/branding as well.

She also deals very well with me sporadically asking for designs and gets them to us when we need them. Couldn’t ask for a better artist to work with because not many would appreciate my scattered brain.

There’s a really cool scene happening right now centered around you guys, Jail Socks, Origami Angel, and Commander Salamander. How have those relationships changed your creative process and/or how you interact with the community?

I mentioned above a bit how Gami’s influenced how I approach songwriting a bit. That whole crew has helped me loosen up in relation to how I present the band online, which helps people relate to us better. I think the biggest thing is the fact that we feel like we belong somewhere now. We didn’t really have that feeling until we started talking to Gami and Comma Salad. We met them and Jail Socks on a tour with Charmer and that was a pretty cool tour for that reason alone. It’s super cool to know we have good people who are great artists backing us.

Earlier this year you released “Tadpole.” How did that song come about, and where does it stand in relation to Happy Again?

I just kind of started trying to write after Happy Again came out. I actually wrote the first riff for Tadpole when we were recording a music video for a song from our four-way split a couple of years ago. I sat on it for a while and then revisited it last year and ended up making a song out of it. We demoed it all out and all liked the song so we were like “let’s go record it.” It’s a pretty solid representation of where our music is going and it’s my favorite song to open our set with. It was actually supposed to be on a split, but I wanted it to be out because I’m impatient.

You’ve posted a video of yourself at sixteen screaming to blessthefall. As someone who also grew up on that “era” of metal, how important was that genre of music on your life? Are there any acts from that scene you’d cite as a major influence on your current vocal style?

It was super important! I still listen to that era of music pretty regularly. I loved mallcore and I was a major scene kid for a bit. I joke around a lot that the song structures I use (or lack of) come from Woe, Is Me and Attack Attack and it’s honestly pretty accurate. Their songs just jumped from part to part and I loved that unpredictability. Vocally, it’s not much of an influence anymore. It was a good introduction to start using my voice in weird ways though!

Where does I’m Really Not That Upset About It stand in your mind? You’ve described it as ‘songs you wrote when you didn’t know what you were doing’ is that just self-deprecation, or a case of three years changing your relationship with the music?

A little of both. I think “Embarrassed” is a good song. I think the rest are okay, but I don’t like my vocals or much of my lyrical content on that EP. I become detached from music I write fairly quickly if I don’t regularly play the songs. I think it was important, and I’m grateful some people cared about it, but I don’t hold any songs close from it besides Embarrassed.

*trying to research Gilmore Girls* Team Jess or Team Dean?

Team Logan

What led you to vocal therapy and how has it changed your approach to performing?

I got super sick and stayed sick for about three weeks. My voice stayed messed up for another couple of weeks. I thought I had a nodule on my vocal cords because I lost a lot of range. My voice kept cracking and didn’t seem to be improving. I had an endoscopy done, which was weird as hell. They said my vocal folds were super irritated, likely from silent acid reflux and allergies. So they put me on meds for that stuff and referred me to the vocal therapist!

It’s made me think a lot about how I treat my voice. I’ve always had a very “fuck it” approach to vocal care and going to vocal therapy has helped me value it. I’m learning a lot about warm-ups and relaxation techniques and breathing and I think it’s going to help a lot moving forward. Especially in the studio, recording for hours a day can get really difficult. I’m hoping what I learn can help in that setting the most.

You post acoustic covers of your songs on social media pretty often. Is this a major part of your songwriting process? Have you ever considered recording a fully-acoustic EP?

I really want to do an acoustic EP, but it’s just a matter of taking the time to do it. I tend to practice songs on my acoustic a lot and sometimes write that way too. I write my vocals while playing on an acoustic pretty frequently. It’s just easier to get a good foundation that way and then adjust when we play full band and I yell a bit more.

You’re about to embark on a nationwide tour with the awesome Origami Angel. Aside from sharing your music, what are you looking to get out of that experience and what’s most important for it to be a rewarding experience?

I’m excited to get closer to my bandmates. I haven’t done a full tour with a single person who will be in that minivan. Gavin joined pretty recently on bass, Sage from niiice. is filling in on drums, and our friend B is tour managing and doing photos and basically being mom. It’s a lot of fresh faces for me and that’s exciting. I’m way excited to meet new people too, including internet friends. I’m excited to play shows in places I’ve never seen before. And we get to hang with Pat, Ry, and Lex (Chatterbot) for three weeks and it’s just going to be so fun. I love those people so damn much.

Being in a band is literally just about saying fuck it and doing something, whether people care or not. No one has to care. The whole point is to make people care and give them a reason. Just doing the tour will be rewarding in itself because we get to show people every night why they should care about what we’re doing.

You can purchase Happy Again on Bandcamp or stream it on Spotify. Stars Hollow is about to embark on a nationwide tour with Origami Angel this summer, find the dates here.

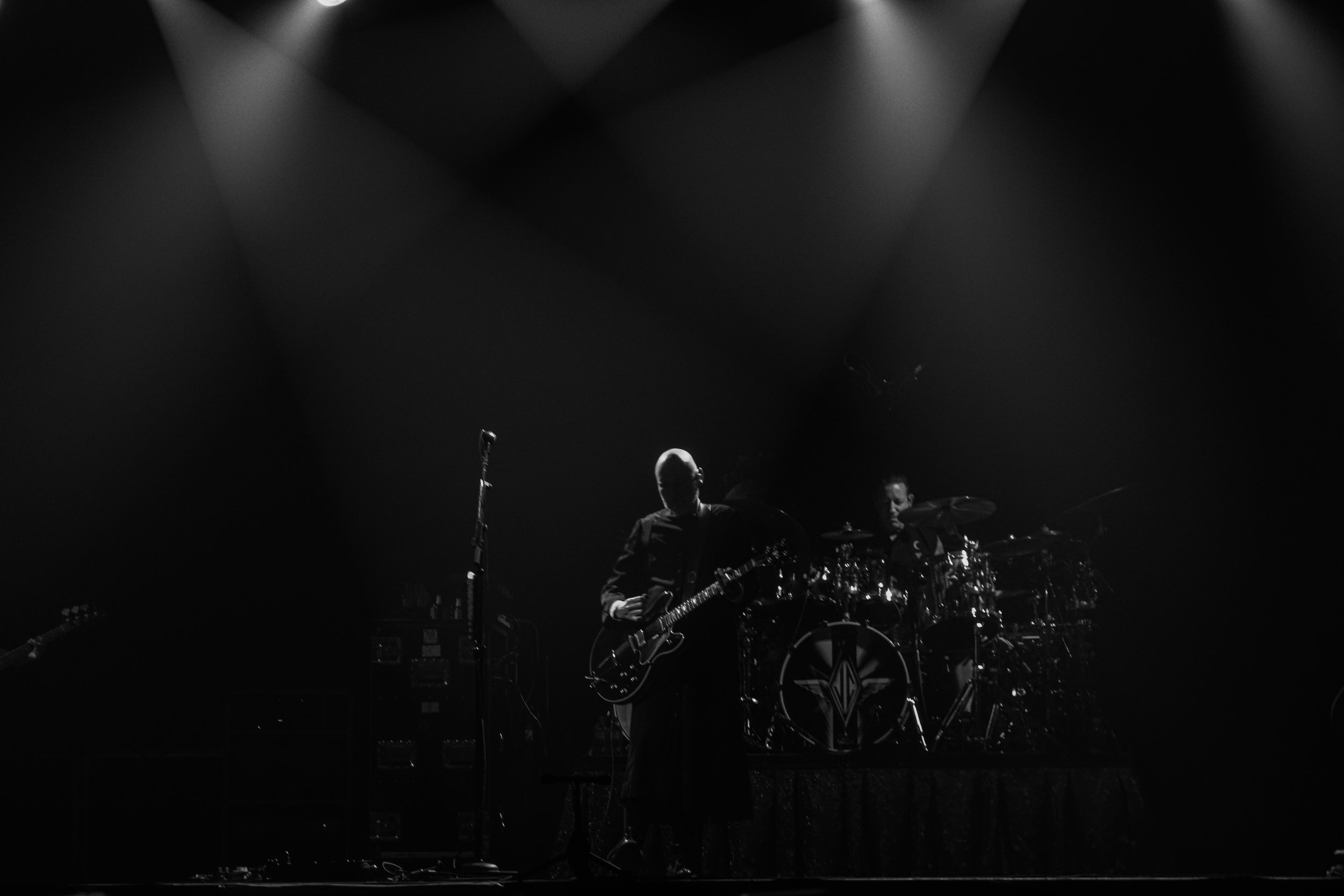

Photos provided by Shiara Crilly.