Welcome to the Ministry of Interior Spaces: An Interview With James Li

/One of the most common words that people use when discussing instrumental music is that it’s “cinematic.” While this is often meant as an endorsement, I’ve always read this descriptor as a bit of a back-handed compliment.

On one hand, this (hypothetical) person is saying ‘this so good it could be in a movie,’ but they’re also saying ‘I view it as background music’ in the same breath. They recognize it as music on a technical level, but the only reference point they have for this type of sound is when it’s pushed to the back of a movie with sound effects and dialogue placed over it. Almost as if it’s not musical enough to stand on its own due to the lack of vocals.

I’ve written previously about my complicated relationship with post-rock and instrumental music, even (lovingly) using the phrase “background music” to describe it. While I stand by that term, the more vital piece of this equation is the listener’s role in the genre’s consumption. Instrumental music rewards its listener regardless of how carefully they’re paying attention. Sure, you can leave instrumental music on in the background, but something wonderful happens when you listen to it actively.

When you put an instrumental record on with the music as your sole focus, the songs gain abilities that they wouldn’t otherwise have. In many people’s minds, this is the “ideal” way to interact with music of any genre, but I recognize it’s not always practical given how much commitment it requires. But when you sit. And kill your senses. And listen. The music can envelop you. It can access forgotten parts of your brain. It can retrieve long-lost memories. It can re-establish broken connections. It can help you feel.

Music serves a purpose for everyone, and each genre possesses different abilities. Instrumental music allows the listener expression, projection, and reconciliation on a level unparalleled by any other genre. It’s the soundtrack to our own thoughts and senses, the backdrop to a mind running wild.

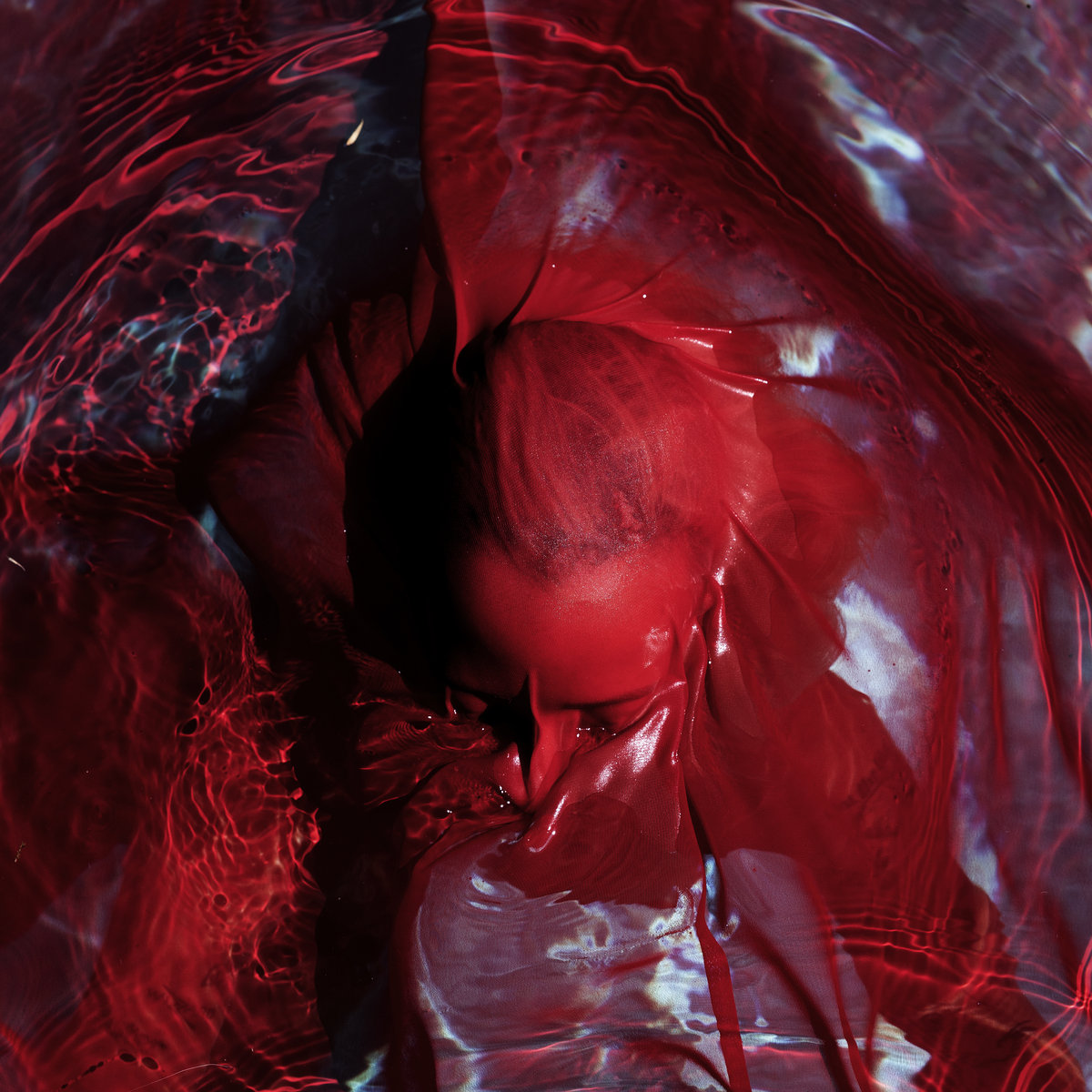

On his newest release as Ministry of Interior Spaces, James Li takes the listener on a “mystical road trip through a magic-realist American West.” It’s a long-winding, heartfelt, and compelling release that means as much to its creator as it can for the listener. With each track named after real-world locations, Li takes inspiration from events in his life and weaves a narrative of recovery in the face of obliteration. While his story remains unspoken, the music acts as both his voice and emotion, carrying the listener from one happening to the next with ethereal grace. It’s a canvas that listeners can engage with, project their own experiences onto, and enclose themselves in.

With (nearly) all of the song titles referencing real-life locations, how do you go about translating the feeling of a place into a song?

James Li: We all experience nature in a way that is subjective and relative to our own selves. There is no truly neutral way of experiencing nature - a family road trip to the Grand Canyon eating from Wendy’s drive-throughs isn’t neutral, but neither is solo backpacking in the Cascades.

As humans we can’t help but experience nature through our own individual-shaped lens. We’re always bringing our personalities, our anxieties, our philosophies, our memories, and emotions to the table. In my case, my worldview was seriously muddied with depression and anxiety. I was dragging a lot of ugliness to these places of often incomprehensible beauty.

There was a definite, discernible conflict whenever this happened. I’d find myself humbled and confused by the natural beauty in front of me - how could so much goodness and pain exist at the same time? So each track isn’t as much of a description of a place as it is a description of that event, that meeting. They’re not describing how the place objectively is but rather how they made me feel at that moment.

On the Bandcamp page you’ve highlighted the fact that this album is two years in the making and recorded across three different continents. What led to such a long incubation period?

James Li: The two years I spent making this album were full of bruising seismic life changes. This included graduating college, leaving Michigan for good, taking an office job in Hong Kong, going through a bad long distance break up, spending some time in the hospital, a confusing visit to the States, then moving to England where I live now. I don’t want to talk about everything because it’d involve people who wouldn’t want to be involved, but it was definitely the most painful and truly nihilistic time of my life. Completing this project was the last thread pulling me through. I wanted to create an album that could justify getting through all of this loss, a reminder to myself that real objective beauty exists.

I had a clear idea of what I wanted Life, Death and the Perpetual Wound (LDATPW) to be early on, taking the atypical move of writing a thesis and track listing before starting recording. Because of that specific vision, I was merciless with what didn’t fit. I cut at least thirty tracks in the making of this album - some turning up on Sister in the Snow, an EP about Michigan I released in the interim.

Writing LDATPW was a huge learning process as well. Through trial and error I learned new methods such as screwing and granular synthesis, which made me constantly retread my steps and revise earlier tracks. For two years my life basically revolved around finishing this album, and at times I wasn’t sure if it’d ever be completed. I only allowed myself to put it out when I was certain it’d been fully realised.

Your other band Liance seems to be a much more “traditional” project with a full band, vocals, etc. What spurred the need for you to create Ministry, and what drew you to the ambient genre?

James Li: Liance is an intensely personal project with little space between what I write and myself. It’s very literal. After releasing Bronze Age of the Nineties I wanted a musical outlet that didn’t have my personhood at the forefront, something completely untied to my ego.

Ministry of Interior Spaces started in January 2016 after playing the indie game Kentucky Route Zero. There’s this one scene where you visit a government agency called the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces. Inspired by the game’s ambient synth score and magic-realist American setting, I wanted to create my own Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces, a “Ministry of Interior Spaces” so to speak. Dying Towns of the Midwest was to be an ambient album from that Ministry’s perspective, a government survey of post-financial crash towns I was familiar with in Michigan.

This was during J-term in the middle of a particularly cold Michigan winter. I’d just bought an OP-1 and slept in a sleeping bag as there wasn’t any heating in my room. I was experiencing serious anxiety about my post-college future and the upcoming presidential election. I was also reading One Hundred Years of Solitude and watching the movie Her to sleep every night, all-in-all a strange headspace to be in.

These different factors somehow came together as the perfect catalyst and I found myself churning out tracks on bus rides and 15-minute class breaks. I made friends at an antique store so I could use their Wurlitzer and recorded a borrowed cello in the kitchen. Dying Towns of the Midwest took just four weeks from conception to publishing, which is quick for any album. Unlike writing under Liance, none of it felt vulnerable even though it was still a deeply emotional process. It felt liberating to create something so completely for myself without the expectation of explaining my lyrics or performing live.

I still consider Liance and Ministry just as important as each other though. They simply occupy different parts of my mind, with the added benefit of being able to jump project-to-project whenever I have a creative block on the other. There’s a lot of narrative overlap as well, although Liance focuses more on memory while Ministry focuses on the spaces they occur in. In fact, the next Liance album covers events described in LDATPW.

On the Bandcamp page you also give credit to all of the various musicians who have contributed to the album, even going as far as to call them ‘collaborators.’ How did you connect with all these people, and what was the collaboration process like?

James Li: I’ve been very lucky to have the musicians I’ve had on this album. All of these connections have been completely serendipitous. Katie Kuffel, who sings on the opening track, used to date my old high school friend during college which is how we know each other. I stayed at her apartment for a week when I started writing this album. It just so happens that she’s also an incredible musician and someone whose work ethic I look up to.

John Denno, who recorded all the brass on the album, reached out to me online after listening to the Liance albums. He teaches at an Indian boarding school which one of my best friends coincidentally went to. I met Josh Frenier, the high schooler who plays drums on the last track, while waiting in line for Pitchfork 2016 with his dad. Those are only just some examples of the many crazy connections on this record. The universe is abundant and I continue to meet exceptional human beings without ever planning to.

I think it goes to show that most people are inherently giving and just want to be part of something beautiful. It’s also a testament to the new possibilities technology has opened. Borders and regional scenes simply don’t matter as much as they used to. There’re stems on this album recorded all around the world, including India, Seattle, Liverpool, New Mexico, Brighton, and Hong Kong. All you need today are good strangers, a decent microphone, and a Google Drive account.

The title of the new LP is Life, Death and the Perpetual Wound. Without giving away too much, what inspired the name of this album?

James Li: Depression, and also just that life itself is inherently painful. The Perpetual Wound is also a theme carried over from the first album, which ends with “The Wounded King.”

The idea of the “journey” seems to be a central concept to both the album and your life. Where did the “concept” of this album come from?

James Li: On Dying Towns of the Midwest I named some tracks after places in Michigan like Holland or Marquette. This was inspired by Bon Iver’s self-titled album, with titles like “Lisbon, OH” and “Hinnom, TX.” On LDATPW I wanted to take this concept one step further and turn a series of imagined spaces into a full narrative.

Worldbuilding and storytelling is inherently fun. It’s in our very blood to mythologise. I’ve always enjoyed science fiction and concept albums, or really just concepts in general, and wanted to try creating a self-contained universe in an ambient album.

The American West is perhaps the most sublime and unknowable place in the world. Its landscapes genuinely changed my life during a period of serious desperation. There’s something truly transformative in the West’s sheer scale of wonder - something spiritual, for lack of a better word. It felt like my duty to pay tribute to its beauty and document what I’d seen.

The idea of a journey came naturally as that was how I’d experienced the American West. Traveling is probably my favourite thing in the world - the notion of free movement and perpetual discovery. It’s something that I’ve been fixated on since a very early age, perhaps because Hong Kong is a small place surrounded by water and borders.

The events covered in LDATPW come from four separate trips to the American West during and just after college. In 2014 I followed some guys on my floor and drove 22 hours straight to Canyonlands for some backpacking, which was my first real encounter with the West. Then in 2016 I headed out to the West three more times - to Seattle over Spring Break after going cold turkey on my SSRIs, to Montana and Wyoming just two days after graduating for a geology course, and New Mexico via Amtrak a few weeks before my visa expired. Each journey was unique, challenging, and utterly transformative.

While designing the album I stitched these separate journeys together as one epic continuous pilgrimage, an album you could draw on a map. It’s a simple way of framing that helps give it a larger sense of progression and meaning, while staying true to the actual personal journeys I’d experienced.

A really fantastic book on the American West and all of its paradoxes is Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey. If you’re able to look past his macho abrasiveness, it’s a perfect summary of this album’s core themes. It also informed some of the poetry on the album’s zine and the lyrics of the last track.

Many people ascribe the “cinematic” label to instrumental music without thinking about the creator behind the art. While you obviously have a deep personal connection to each of these songs, what’s more important to you: the idea that your story is captured on these tracks, or the process of the listener imprinting their own emotions onto them?

James Li: The listener’s experience should always take precedent. It’s my hope that people continue to project their experiences onto my music. My favourite aspect of working on this project are the completely different takeaways people get from the same tracks. “This reminds me of an aquarium I went to when I was five,” or “This track totally brings back college summers in Lake Michigan.” Hearing memories like these gets me super excited. It means more than any good review could.

And that’s the beauty of ambient music I think. You get to choose your level of engagement, and however you interpret it is yours to own.

While some musicians may disagree, I see making music as essentially creating a tool. It’s a noble and necessary thing to do, but you’re still ultimately creating something that exists outside of yourself for others to use. When someone likes your music, they like the tool that you’ve created, not you. Your relationship to what you’ve created shouldn’t matter as it exists independently on its own. And that’s kind of freeing, you know? You get to contribute back to the world without forcing your ego onto it, and the people who need to find your music will find it eventually.

Stream Life, Death and the Perpetual Wound here, or pick up a copy on Bandcamp.

Read James Li's track by track analysis here.