Swim Into The Sound’s 13 Favorite Albums of 2025

/What can I say about 2025 that hasn’t already been said across numerous publications, think pieces, and vent sessions? I guess I’ll start (selfishly) with my own experience as 2025 was a year of displacement, awkward liminal holding patterns, and stringing things together. About halfway through the year, I moved from North Carolina, leaving behind a place that felt “my speed” and was home to one of the most welcoming creative communities I’ve ever been part of. I also spent months looking for a job, facing down rejection after rejection, which is a uniquely demoralizing and confidence-destroying way to spend a year. Way I figure, all you can do in a situation like that is try to keep things light and moving forward.

The upside was that this lack of vocation meant lots of freedom and experimentation. At the beginning of the year, I instituted my own weekly column and monthly roundup just to keep myself writing regularly. I rekindled my love of photography and launched a new wing of this site dedicated to concert photos. I made a fresh batch of Swim Into The Sound merch (shirts, totes, lighters, stickers!) and tabled our first-ever event at a festival that has been nothing short of formative to my musical identity. We also made our first zine, hit 500 articles, and turned ten years old! It was a banner year in Swim Land that also happened to be our most-trafficked ever, all with fewer posts than last year, so I’ll chalk that up to quality over quantity. I couldn’t have done any of this without the beautiful Swim Team, and if you wanna know what music they liked this year (besides “Elderberry Wine”), you should click here. I hope this continues to be a place where cool people can share cool music they love.

In the end, I did find a job, and it's one that I am immensely excited to start in the new year. It’ll be a new chapter of my life and, presumably, this site as I find equilibrium in an entirely new environment. Now that I’m looking back, 2025 felt like a really weird self-contained bottle episode of sorts. Apologies in advance if things feel slow or disjointed in the new year. I think there’s still lots of “figuring stuff out” ahead of me, but at least now I feel some direction, which is a blessing after 12 months of floating around and trying my best.

Okay, but who the hell am I?

I am a dork-ass nerd who listens to way too much music. My choice for album of the year matters just as much as yours. You can read that statement as positively or negatively as you like, but I see it as freeing. We all have different answers to the AOTY question, from the lowly Taylor Swift devotee to the buzzy Bandcamp-only group that Pitchfork has exalted this year. To some end, those answers themselves are meaningless; what actually matters is why.

This year, I sat looking at some of my favorite albums of 2025 and questioned if it was all too expected. It’s not quite this, but many of these bands feel like related artists who tour together, play on each other’s songs, and could easily be played in sequence at a cafe that has let the algorithmic radio play out too long. Does it feel redundant? Am I offering enough trenchant insight to warrant this? Where do I get off?

If all the first-person language so far wasn’t a tip-off, “Swim Into The Sound’s Favorite Albums of 2025” is really just “Taylor’s Favorite Albums of 2025” dressed up to resemble the type of year-end list you’d find at a more buttoned-up publication. This is a tradition I’ve kept up for ten years, so there’s no stopping it now.

Ultimately, the goal for this type of article is to be as representative of my year as possible. Sure, it’s ranked, so I guess there’s some value judgment here, but make no mistake: this is a love fest. These are all records that I listened to endlessly and found comfort or catharsis in throughout the year. The goal is for me to look back and say ‘oh yeah, that’s what 2025 sounded like…’ I think a certain type of person might still find something new here, but at the very least, I hope you find a new way to look at an album you’ve already heard.

This year, we’re going with a baker’s dozen. Sure, it’s ranked, but the difference between, say, #8 and #9 on a list like this is about as nebulous as it gets. I can assure you I’ve got an even bigger list about a hundred albums long, and while it can feel funny to affix a number like “66” to a record, to me this is a celebration, not competition.

In so many ways, this was a terrible year of backsliding, regression, malicious intent, and horrible cruelty. I think it’s right to button things up with some positives before sending 2025 off to the annals of time—so long and good riddance. Here’s hoping we take the next step forward together, taking on whatever comes at us with renewed energy, vigor, and intent.

Look out for each other and love each other, it’s kinda all we have. In the meantime, here are 13 albums that helped keep me sane and understood in a year of free-floating dread and looming anxiety. Hallelujah, holy shit.

13 | First Day Back – Forward

Self-released

For every “real emo” copypasta, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. For the ongoing Mom Jeans-ification of Midwest Emo, I like to imagine there’s a group like First Day Back upholding a more rigorous and truthful version of the genre, rooted in something more profound. Forward sounds like a forgotten classic, lost behind the shelves of a Pacific Northwest record store between Sunny Day Real Estate and Sharks Keep Moving. Throughout their debut, the Santa Cruz band tap into a second-wave style of emo that does my soul good to hear in the modern era. There’s no shortage of forlorn vocals or wandering instrumentals that offer plenty of space to contort in contemplation and writhe in regret. A true-blue emo release that should appease the oldheads and help the kids wrap their minds around a different way to approach these feelings. It’s overwrought because it has to be. After all, that’s the only way you feel anything at this age. And that is real emo.

12 | Ribbon Skirt – Bite Down

Mint Records Inc.

Early on in 2025, I was listening to an advance of Bite Down and was struck with the realization that it was one of my favorite records of the year thus far. In a world where the bands you know and recognize offer the false comfort of familiarity, here was a record I wandered into with zero knowledge or preconceived notions, and I found myself utterly floored by. While it’s technically the Montreal band’s debut, Ribbon Skirt was formed from the ashes of Love Language, so this new name and project feel like a fresh start that allows them to be even more intentional and fully realized. This is a band that knew what kind of music they wanted to make and achieved their vision with stunning clarity throughout these nine tracks. Bite Down is packed with dark, enchanting grooves that are even more mystifying to witness live. Lead singer Tashiina Buswa pens lyrics that can be cutting, angry, and funny all at once – a combination of emotions that feel like an appropriate way to face down the absurdity of life in the modern age. There’s betrayal, confusion, displacement, and, at the end of it all, the band summons a pit to swallow everything up and return the world we know into the gaping maw of the universe, washing it all away in the blink of an eye.

Read our full review of Bite Down here.

11 | Michael Cera Palin – We Could Be Brave

Brain Synthesizer

There’s a joke I like to say, and I can’t remember if I picked it up from somewhere or arrived at it organically, but it’s a bit of a sweeping statement: every band name is bad except for Mannequin Pussy. That’s true to the nth degree for Michael Cera Palin, a band whose name sounds like an emo group from a decade ago because they are. The crazy thing is, the music is so fucking good that it redeems the corny name to the point where I don’t even think about it until I’m saying it out loud.

To give a brief history of the Atlanta indie-punk group: they released two EPs at the waning crest of fourth-wave that I genuinely believe to be without flaw. Between COVID, lineup changes, and just about every obstacle you could imagine, We Could Be Brave is the group’s first official LP, and it’s everything I could have hoped for. The thing kicks off like a powderkeg with immaculate guitar tone and hard-driving bass, peaking in an ultra-compelling cry of “FUCK A LANDLORD, YOU CAN'T TELL ME WHERE I LIVE!” There’s an incredible spoken word passage, powerful singalong singles, a re-recording for the realheads, and a 12-minute closing title track to really send ya off with a kick in the pants. Throughout it all, the band is utterly restless and proficient, a perfect conduit for the transfer of energy that this type of music aims to achieve. The rare great emo album, the rare seven-year wait that was worth it, the rare god-awful band name that doesn’t give me a second of pause.

Read our full review of We Could Be Brave here.

10 | Greg Freeman – Burnover

Transgressive Records

I love the first Greg Freeman album. There was a whole summer where I kept I Looked Out on maddening repeat, wrapped up in its alien twang and distortion. It’s the exact kind of sound that’s in vogue right now, so it only makes sense that Greg Freeman is already onto the next thing. Greg’s second album, Burnover, is a dirty, dust-covered, shit kicker of an album, packed with lounge singer swagger, funny-ass phrases, and open-road braggadocio. Opening track “Point and Shoot” is something of a test to see how well the listener can handle Freeman’s off-kilter voice as he paints backdrops of blood-soaked canyons, senseless tragedy, and a wild west with the power to make you recoil. Beyond that, the horns of “Salesman” and the honky tonk piano of “Curtain” offer riches beyond this world. Mid-album cut “Gulch” revs to life with the heartland verve of a Tom Petty classic, encouraging you to hop in your car and hit 80 on the closest straightaway you can find. If the album’s charms work the way they’re intended, by the time he’s singing “Why is heartache outside, doing pushups in the street?” the question should not only make sense, but the answer should hit you like a punch in the gut.

Read our full review of Burnover here.

9 | Florry – Sounds Like…

Dear Life Records

Sometimes, one sentence is all it takes to sell you on a record. In the case of Sounds Like…, there was a standalone quote on the Bandcamp page, rendered in hot-pink type, that reads, “The Jackass theme song was actually a really big influence on the new album.” Hell yeah, brother. Between the time it took me to read that and watch the homespun handycam music video for lead single “Hey Baby,” I knew I was in for a good time. Sounds Like… is an album that sweats, shouts, yelps, and stomps its way into your heart through nothing but the glorious power of rock and roll. Opening track “First it was a movie, then it was a book” is a joyous seven-minute excursion, complete with glorious guitar harmonies and countless solos – a perfect showcase for lead singer Francie Medosch’s scratchy, charismatic voice. Throughout the rest of the album, you’ll hear sweltering harmonica, walloping wah-wah, beautiful acoustic balladry, smoky, head-bobbing riffage, and sincere love songs. Sometimes ya just gotta sit back, let the guitars rock, and enjoy watching the frontperson be a wonky type of guy you’ve never seen before. While their sound is obviously very steeped in the tradition of “classic” rock, on this album, Florry sounds like nothing but themselves.

8 | Colin Miller – Losin’

Mtn Laurel Recording Co.

Colin Miller might be the Fifth Beatle of the “Creek Rock” scene. He’s the Nigel Godrich to Wednesday’s Radiohead; the rhythmic center keeping time in MJ Lenderman’s band; the invisible fingerprint on a whole host of this year’s best indie rock records. On his second solo album, Miller proves that he’s also a knockout musician in his own right. While I enjoyed the singles, to me, the only thing you need to understand Losin’ is to start it from the top and take in that sick-ass guitar bend on “Birdhouse.” If that hits you, then you’re in for a treat.

Essentially an album-length eulogy, Losin’ is a record about Gary King, the beloved owner of the Haw Creek property, which served as artistic home for the aforementioned Wednesday, MJ Lenderman, and many more from the now-dispersed Asheville music scene. This is an album that wrestles, fights, makes up with, and finds painful coexistence alongside loss. It’s not just the loss of a father figure and a home, but a time, place, and person that you’ll never be again. It’s about how things will always feel different, and might feel bad, but will unfold all the same. The tasty licks help things go down easier, but this is a heartrending record made for moping and wallowing in the name of moving on. After all, it’s what those lost loved ones would have wanted.

Read our full review of Losin’ here.

7 | Geese – Getting Killed

Partisan Records

Whenever life has felt hard this year, I can’t help but feel guilty knowing that I don’t have things that bad. All things considered, my struggles feel frivolous compared to what some have to deal with on a daily basis, and that worries me for the future. Put another way, I’m getting killed by a pretty good life.

It seems impossible to write about Geese without being a little annoying, but maybe that’s just because I know a lot of music writers and have read a lot of hyperbolic Geese writing this year. They’re the band saving rock. They’re the band holding up New York as an artistic center of the universe. They’re the ones topping lists and starting trends and getting people to wash their hair differently. Ultimately, I’m just glad that kids have a proper band to look up to who will lead them to Exile and Fun House and to start their own stupid, shitty rock bands that don’t go anywhere. We need more of those.

If anything, I am a Geese skeptic. If anything, I prefer the dick-swingin' classic rock riffage that was more abundant on 3D Country. If anything, I think this band’s most interesting work is still in front of them. Even still, it’s hard to deny the beauty of a song like “Au Pays du Cocaine,” the snappy drumming of “Bow Down,” the rapturous ascension of “Taxes,” or the pure, wacked-out fun of shouting “THERE’S A BOMB IN MY CAR!” Overall, Getting Killed may take a slightly slower pace than I would have wanted, but it’s nice to have a cool, weird rock band making cool, weird rock music that people seem to be excited about.

6 | Alex G – Headlights

RCA Records

Headlights is an album that feels like it was meant to exist as a CD in the console of your family car. It’s a shame this wasn't released between the years of 1991 and 1998. This is an album that has grown on me immensely over time, and much of that enjoyment comes from throwing it on and letting it play from the top. Headlights has a rough, road-ready quality that puts it in the league of albums like Out of Time or Being There – records meant to be thrown on repeat endlessly and live between the seats of a beat-up Dodge or the family van. Maybe listened in five to 15-minute chunks while running errands across town, maybe on a road trip blasting through the middle of the country. In any case, the tenth album from Alex G doesn’t necessarily stun or wow on the outset; instead, its power comes from these repeated visits, slowly growing, morphing, and solidifying over time into a singular thing. Definitely a grower, not a shower, but hey, who among us? After directing scores for two of the most interesting indie films of the past decade, Alex G seems to have picked up a couple of interesting lessons about restraint and leaving some sense of mystery. Headlights is a record that rewards patience with beauty, unlocking compartments and passageways for those willing to explore. In time, I think this record will work its way up my ranking towards the upper-crust of Alex G records, but maybe I’m just unavoidably 32, and this is the type of music I’m drawn to. Time will tell.

5 | Spirit Desire – Pets

Maraming Records

In the weeks after Pets released, I distinctly remember asking myself the question, ‘Can a four-song EP be in the top ten on my album of the year list?’ Technically, Pets is really only three songs and one 90-second instrumental interlude, but I suppose that lightweight feeling is part of the appeal; less songs means less space for error, and when four out of four songs hit, you start to think of this as a 100% hit ratio. While the first song delves into the title at hand, reckoning with dead pets over shimmering keys and a nasally Canadian-emo accent, “Shelly’s Song” offers an immediate portal that cleanses the palate for what’s next. What’s next is “IDFC,” one of my favorite songs of the year and a track that connects to me with the same lightning rod intensity of something like “Assisted Harikari,” an absolute jolt to the system and the type of song that reminds me why I like music so much in the first place. Admittedly my buoy for this entire release, “IDFC” begs you to jump into the pit and scream your heart out, while “It Is What It Is” swoops in to mop up the sweat and spilled beer. I know Pets isn’t an album, but the enjoyment I’ve gotten out of these ten minutes outweighs entire LPs, adventures, and days of my life—a perfect excursion.

4 | Algernon Cadwallader – Trying Not to Have a Thought

Saddle Creek

It sounds a little hyperbolic, but when Algernon Cadwallader released Some Kind of Cadwallader in 2008, it more or less birthed the modern emo scene. There are still bands today that cite Algernon as an inextricable influence. Sure, emo music still has deeper ties to American Football and Rites of Spring, but Algernon was the Revival. In fact, they were so good, they couldn’t even top themselves. The group released Parrot Flies in 2011, then decided to take a hiatus in 2012. A couple of years ago, they did the Anniversary Thing and toured with the original lineup, which felt so good that they signed to Saddle Creek for Trying Not to Have a Thought. Never mind the Emo Qualifier; this record is the absolute best-case scenario for a band reuniting and recording a record, up there with Slowdive and Hum.

Perhaps one of the strongest things working in its favor is that this is decidedly not the band just trying to sound as close as possible to their fan-favorite album; instead, they’re taking those techniques and approaches and updating them to where they find themselves in life now, which is to say, grappling with an entirely different set of problems. While the early music was earnest and obscure, Trying is earnest and pointed. There’s no longer time to beat around the bush because there are real stakes. This record touches on everything: death, technology, work-life balance, and the 1982 non-narrative documentary Koyaanisqatsi. When those concepts seem too big, the band zooms in on hyper-specific examples, detailing them with colorful brush strokes that are impossible to rip away from.

On one song, vocalist Peter Helmis shines a light on millions of dollars of rocks that the city of Portland, Oregon, had installed to keep homeless people from sleeping under an overpass. One song later, the band recounts Operation MOVE, in which our own government dropped two bombs on a Philly neighborhood that housed the black liberation organization MOVE, killing six adults, five children, and leaving hundreds homeless. It’s pretty stunning to hear a band age this gracefully and create a work that feels like it stands alone. The decades separating the band’s first album from their most recent show that the members are all more mature, proficient, and outspoken. In the end, the band themselves sum everything up smack dab in the middle of the record, where they sing, “You’re ready all too ready ready to accept that this is the way it’s always been and so it must not be broke.” We are radiators hissing in unison.

Read our write-up of Trying Not To Have a Thought here.

3 | Ryan Davis & the Roadhouse Band – New Threats from the Soul

Sophomore Lounge

Ryan Davis is a verbose motherfucker. The average track length on his project’s sophomore album is eight minutes. Recommending that to a casual music fan makes me feel like those people who talk about decades-running anime series and say things like “it really picks up like 300 episodes in,” but I swear that, in this case, patience pays off. In fact, I don’t think you even have to be that patient: go listen to the opening song, title track, and lead single “New Threats from the Soul,” and you’ll pretty immediately understand what this album is “doing,” which is to say loungy, multi-layered sonic expeditions into the heart of the increasingly fragile American psyche. There’s synth, snaps, flutes, and claps. There are shaky statements of love, glimpses into a kingdom far, far away, and an unshakable disconnect between the life expected and the one being lived. At the center of it all, we find Ryan Davis attempting to piece a life together with bubblegum and driftwood, flailing as the band flings back into the groove.

This sort of energy is scattered all across New Threats from the Soul, each song offering a vast soundscape, hundreds of words, and enough of a runway to really feel like you’re along for the ride. Each track pulls you along, adding some lightness and brevity exactly where it’s needed as you are comforted, consoled, and compelled by the pen of Mr. Davis. There are just as many ravishing turns of phrase as there are striking instrumental moments, like the country-fried breakbeat on “Monte Carlo / No Limits” or the winding outro of “Mutilation Falls.” It all adds up to an album that you’ll keep turning over, parsing different layers of a dense text and coming up with something new each time.

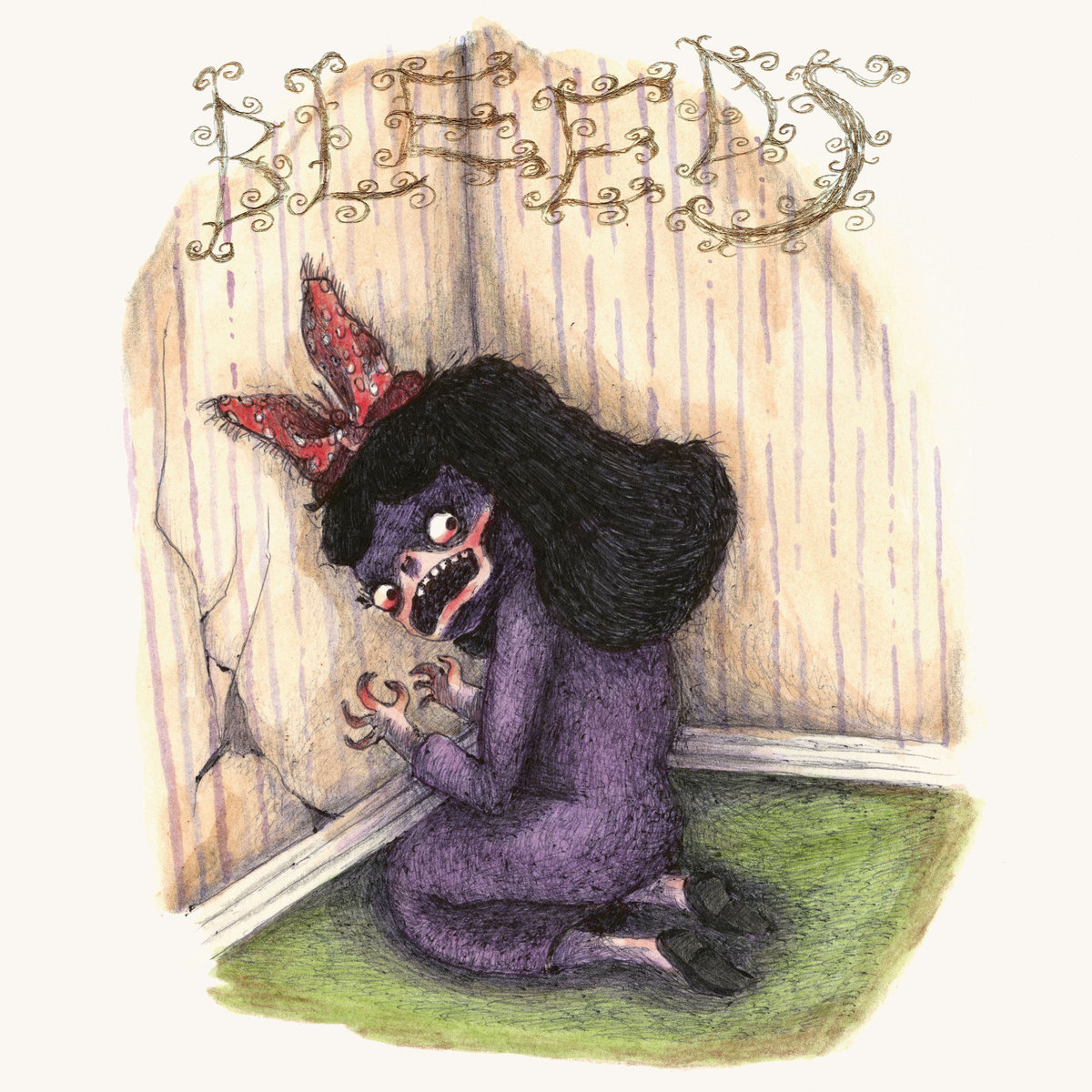

2 | Wednesday – Bleeds

Dead Oceans

The new album from Wednesday is perfect. It’s also expected. Expected in that those who have been following the group for years pretty much knew what to expect from the band’s tightrope walk of country, shoegaze, and cool-ass southern indie. Expected that the band has refined this formula to the point of perfection. Expected that it earned them lots of media coverage, interviews, and sold-out shows after the album before this did the same. The only reason I’d still give an edge to an album like Twin Plagues is that everything felt that much more surprising and novel when it was my first time experiencing it. Even still, it’s a delight taking in the world through the eyes of bandleader Karly Hartzman, who writes, pound-for-pound, some of the most charming, personable, and compassionate lyrics of any modern artist. Her words hone in on small details that others might pass over, wielding them into pointed one-liners, surprising pop culture references, or brand-new idioms that just make inherent sense.

Bleeds still has plenty of surprises: an Owen Ashworth-assisted romp through a double-header of Human Centipede and a jam band set, a rough-and-ready crowd-churning rager, a Pepsi punchline to wrap the whole thing up. This is the most Wednesday album to date: a sort of album-length self-actualization brought about by five of the most talented musicians our United States has to offer. Each time I venture into the record, it is utterly transportive. As “Reality TV Argument Bleeds” mounts to a piercing scream followed by a blown-out shoegaze riff, it’s impossible to want to be anywhere else. This is Wednesday to a tee. The band has condensed their sound to the point of maximum impact, and while I look forward to many more live shows jumping around to “Townies” and singing along to “Elderberry Wine,” the mind reels wondering where they all could take this next, because the answer truly feels like it could be anywhere.

Read our full review of Bleeds here.

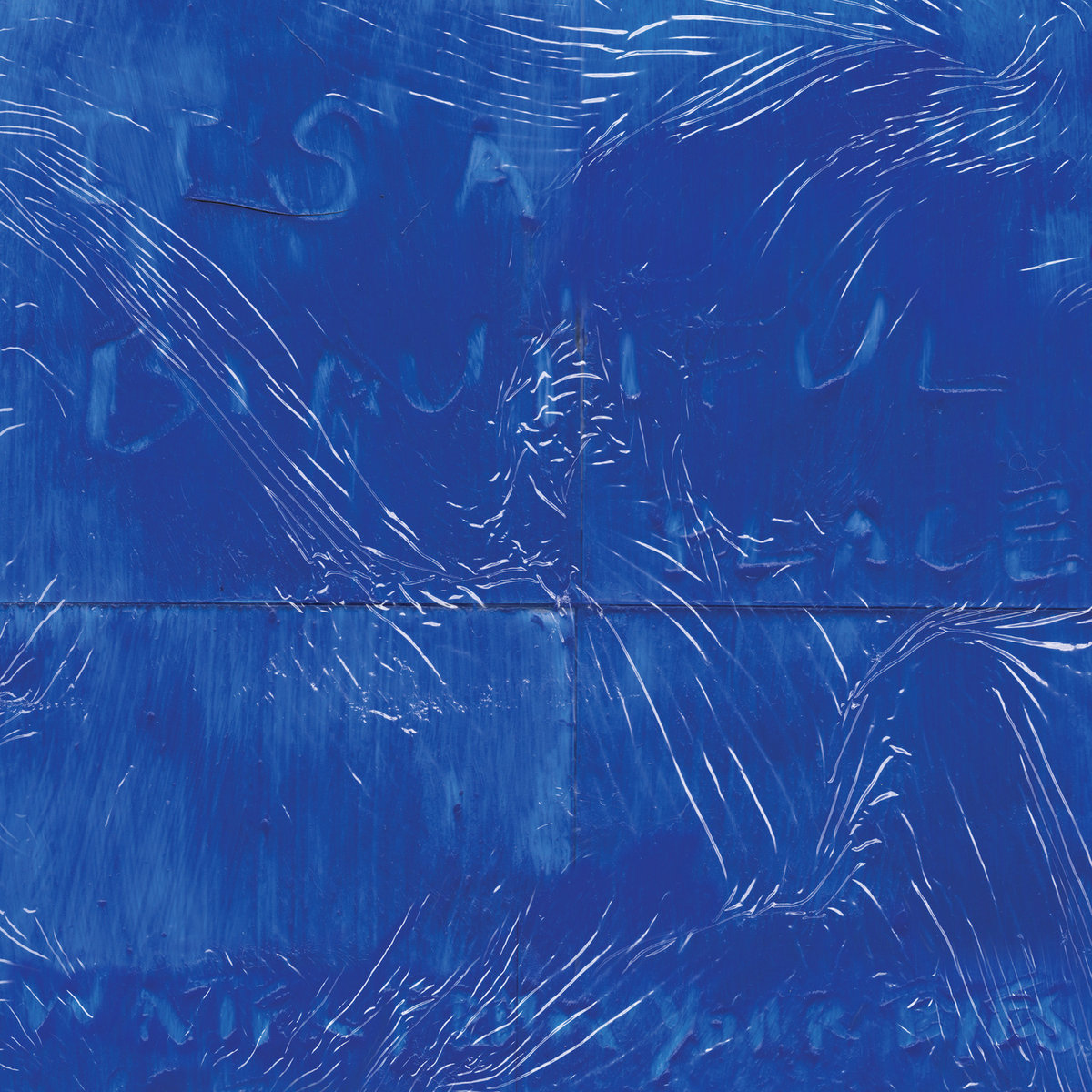

1 | Caroline Rose – year of the slug

Self-released

Dear reader, let me ask you a question… Do you like the way things are right now? Are you happy with The Arrangement? Content to sit back, uphold the norm, and wait for things to get better? Odds are, your answer is something along the lines of ‘fuck no,’ and that’s why you’re here reading this. I’m speaking broadly, but only because this dissatisfaction is omnidirectional and widely applicable. We’re not solving any of the world’s systemic issues in the opening paragraph of a DIY publication’s album of the year roundup, but maybe we can break things down and make it feel more digestible.

This summer, news broke that Spotify CEO Daniel EK was investing 700 Million Euros into Helsing, an AI defense company that primarily makes drones and surveillance systems. As a response, hundreds of artists pulled their music off Spotify and users quit the platform in droves out of protest. The same thing happened a couple of months later when Spotify started running ICE recruitment ads while members of the organization were actively terrorizing citizens in Portland and Chicago.

It feels especially prescient then that when Caroline Rose announced year of the slug back in January, she specifically went out of her way to outline that the album would not be on Spotify or any other streaming platform besides Bandcamp. Similarly, when Rose took the album on the road, they only toured independent venues; the kinds of places that are simultaneously an endangered species and the backbone of the music industry. Between all of this –the AI music, the Live Nation monopoly, the merch cuts, the shrinking margins, and the execs who can only think in terms of statistics and streaming numbers– Rose carved out space to release a collection of songs entirely on their own terms.

year of the slug is a masterful, enchanting, intentioned, personable, honest, and singular collection of songs that function in the exact way an album should. Even just by breaking out of the Spotify Cycle of constantly-flowing new releases that treats music less like art and more like “content,” Rose made a record that you have to go out of your way to intentionally experience and listen to. This alone forces you to engage with the music on a more thoughtful level, experiencing the record on its own terms, not as part of a queue.

In that same album announcement, Rose explained the sort of philosophy behind the record, contrasting that, “in lieu of A.l. perfection, slug contains the sounds of my life–cupboards slamming, birds chirping, the garbage trucks that plague me every Thursday.” The result is a pared-down batch of songs that sound beautifully flawed and human.

The album was tracked on GarageBand through Rose’s phone, so things typically revolve around the most basic of musical ingredients: vocals and an acoustic guitar. While on one hand you could hear that and think “this sounds like unfinished demos,” it could just as equally evoke the stark, barebones imperfection of an album like Nebraska. I personally tend toward the latter, with the minimal arrangements only serving to highlight the elements that do come through. There’s no room for anything to get muddled or washed out. To borrow a phrase from the opening track, everything in its right place, especially the fuck-ups.

The songs themselves are brilliant, with Rose’s ear for melody and knack for sticky phrasing shining on nearly every track. Whether it’s the piercing hurt of “to be lonely” or the spaghetti western stomp of “goddamn train,” year of the slug is an album that delights in the simple pleasure of a sip of Mexican beer and the raw humanity of a Taco Bell order. What’s more, this is an album where I can glance at the tracklist, read a song title, and immediately call to mind what it sounds like. Can’t say the same thing for most records I listened to this year.

To close, I’d like to ask the same question I did at the beginning of this entry: Do you like the way things are right now? If the answer is no, I think it’s time to make a change. It doesn’t have to be all at once; it doesn’t even have to be multiple things. You don’t have to quit everything, leave society, and lead a hermetic life. Maybe it’s just as simple as taking the $10 you give to a company each month and directing it to an artist on Bandcamp to experience their album. I think that’s more rewarding than clicking on a stream, chasing “scalability,” following virality for the next big thing. This could be your next obsession, and that’s the only one that matters.