I like a band called Fugazi from Washington D.C.

/Patience

I was straight edge until a few months before my 21st birthday. I acted as if it were a political stance, similar to what Ian MacKaye laid out in the term-defining Minor Threat track. I told people that I didn’t need to get fucked up to have fun, but I knew in my heart that I was afraid of loss of control. What would I reveal if I got drunk? Would I tell the boys that when I was a kid and dreamed about being a parent that I saw myself as the pregnant one, even though I was assigned male at birth? Would I explain that I expected someday to become a woman? I knew before elementary school that boys shouldn’t think that way and worked hard to fit in. I wouldn’t let a moment of drunken stupidity betray my years of effort to maintain.

Most of all, I was worried about what a moment of not repressing would show me about myself.

All my life was about repression, and that did not stop when I started taking up vices. I did not come to terms with my gender the first time I tasted gin. This is not a pro-alcohol piece; my abstinence is emblematic of how my mind acted in self-defense from socially enforced interpretations of what it means to be a man. I was afraid of not existing rigidly. I wanted so badly not to want. To conform. It infuriated me I that didn’t feel right around the boys, and that the girls didn’t want to be my friend. I sat in a room for years waiting to be called for my turn, mistakenly believing it would come soon and wasting my time.

I wish I could say hearing “Waiting Room” for the first time changed my life instantaneously, but for a long time, it was the only Fugazi song I knew, and it was only just a fun song. I was big on Minor Threat, and anytime I got past “Waiting Room” on 13 Songs and into the Guy Picciotto-fronted “Bulldog Front,” I would bristle slightly because it wasn’t the hardcore I wanted.

But “Waiting Room” isn’t just a fun song; it’s a manifesto. The first song on their first EP, 7 Songs, “Waiting Room” lays out Fugazi’s statement of purpose from the jump: they will not wait for someone to provide them a function, they will form one themselves. While every other band played more expensive shows, signed to massive labels, and took on brand deals, Fugazi defined their objective as anti-exploitation. Shows were $5 until they adjusted for inflation. Dischord Records keeps their records priced at $18. Almost all of their hometown shows were benefits for organizations like the Washington Free Clinic, the Washington Inner City Self-Help & After School Kids, or The Community for Creative Non-Violence. If not a benefit, they played protests against injustices like the Gulf War, budget cuts for essential services in D.C., or Reagan’s war on drugs.

“For marketing the use of the word generation / a false alliance of money persuading”

– “Target” from Red Medicine, Guy Picciotto

MacKaye has a metaphor for how he crafted songs for Minor Threat versus Fugazi that I hope you’ll allow me to butcher. Minor Threat songs presented an idea fully formed, like a shirt, whereas Fugazi songs were the fabric from which to make a shirt. “Waiting Room” is a scrap that poses the question of what you will do with your limited time. Are you a patient boy, or are you going to make a functional key to the waiting room? “Waiting Room” is a call to all of us to take our chances, one that took me years to heed.

Through the Haze

My way into Fugazi was In On the Kill Taker. I don’t remember why I decided to listen to it. I could have been prompted by a video essay I watched that referenced this as the most straight-up “punk” of the records. I could have been drawn in by the hazy yellow cover with the Washington Monument looming like a monster. I could have questioned the cryptic title: what is the kill taker, and who is in on it? Regardless of what it was that got me through the door, the moment the phone line guitar noise started, I was in. Then the drums and bass built up. Then it all dropped to just chicken scratch guitar driving ahead, and then there was Ian MacKaye, massive in my mind, screaming that “pride no longer has definition.”

I didn’t know what MacKaye was barking throughout “Facet Squared,” his voice far less clear than any Minor Threat song. I didn’t know what he was saying should never touch the ground. I didn’t know what he was saying was always dated. I didn’t know why we were drawing lines to stand behind. But I knew this was it. I knew this album would be what helped me get Fugazi, especially when the Picciotto-fronted “Public Witness Program” pulled me in closer, unlike “Bulldog Front.”

In On the Kill Taker became everything to me. The hazy cover photo belies the clearly focused vision of the band and its philosophy. Detractors of Fugazi have long accused the band of merely preaching, dictating to the audience, as if their songs were gospel to follow. But when you listen to the songs on Kill Taker, it is hard to maintain that belief. “Returning the Screw” questions a set of peers who poked fun at Mackaye on their album cover. “Rend It” is one of the most devastating love songs as Picciotto pleads to give himself wholly to his lover. “Great Cop” isn’t about policing; it’s about trust in interpersonal relationships. The title “23 Beats Off” is not an inversion of Magic Johnson’s number, as myth goes, but it is a wrenching piece about the dominant society in the U.S. refusing to care for the queer people ravaged by the AIDS pandemic. “Last Chance for a Slow Dance” is a vision of debilitating loneliness distilled into the simple imagery of the verse: “Flare / flare fakes a flower / a burnt-out shower / no one can see.”

The ode to Hollywood iconoclast John Cassavetes, on the aptly titled “Cassavetes,” is one of my favorite ideas Fugazi ever explored. The work of Cassavetes, as described by Picciotto, jars you with a presentation of the hyperreal. Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence is one of the only films I’ve treated as background noise on my first watch. I simply couldn’t bear to give full witness to the crumbling psyche Gena Rowlands depicts in the film, as it reminded me too much of my life growing up.

That is the caliber of art Fugazi are aspiring to. Their aim isn’t to make propaganda but to present you with something that will force your mind to take aim at something new.

MacKaye often speaks in his talks about the way skateboarding forced him to make new connections, and Fugazi’s music does that for me. On Red Medicine’s opener, the thrilling rush preceded by a blown-out practice tape that sounds more like heavy machinery than punk music, but when the song bursts out, Picciotto sings about the then-new merger between arms conglomerates Martin Marietta and Lockheed, their offices burning down, prison construction, jets crashing, and stained glass, all in the context of asking a crush that simple question in the title. I’d certainly never thought about intimacy between two people as comparable to corporate intrigue.

But sure, there are moments of directness within Fugazi’s catalog, especially within their earlier material. Repeater, the band's first full album, features the call and response “You wanted everything / you needed everything” on the rager “Greed.” I can understand being put off by how “simple” the lyrics are, especially in comparison to the Picciotto-penned preceding track, “Sieve-Fisted Find,” which decries hollow solutions for desperate problems, but when MacKaye screams “everything is… / greed” to close out the track, you realize there doesn’t need to be more. Why disguise your anger?

Repeater is one of those first albums a band puts out that feels disingenuous to refer to as a “debut.” The step from their first two EPs, compiled on 13 Songs and the 3 Songs EP, that is now tacked onto the end of Repeater on streaming, is nowhere near as large a gap as that between any of their further albums. Part of this comes from the fact that the tracks on Repeater existed for a long time. “Merchandise” appears on their first demo and the setlist for their first show, and “Reprovisional” is a rerecording of the Margin Walker cut, “Provisional,” but now with Picciotto playing second guitar. The persistence of those tracks indicates the other factor for why the leap from EPs to album doesn’t feel as momentous as other debuts. It’s the same reason even people like my punk-averse girlfriend like “Waiting Room” – Fugazi feel eternal, as if they were dropped into the universe fully formed the moment that bassline starts.

I say ‘feel’ for a reason, because the myth is always sexier than the truth. If we just had the records, there would be a compelling case for the myth to be the dominant story. But instead, we have the Fugazi Live Series to complicate that story.

You Don’t Need a Reservation

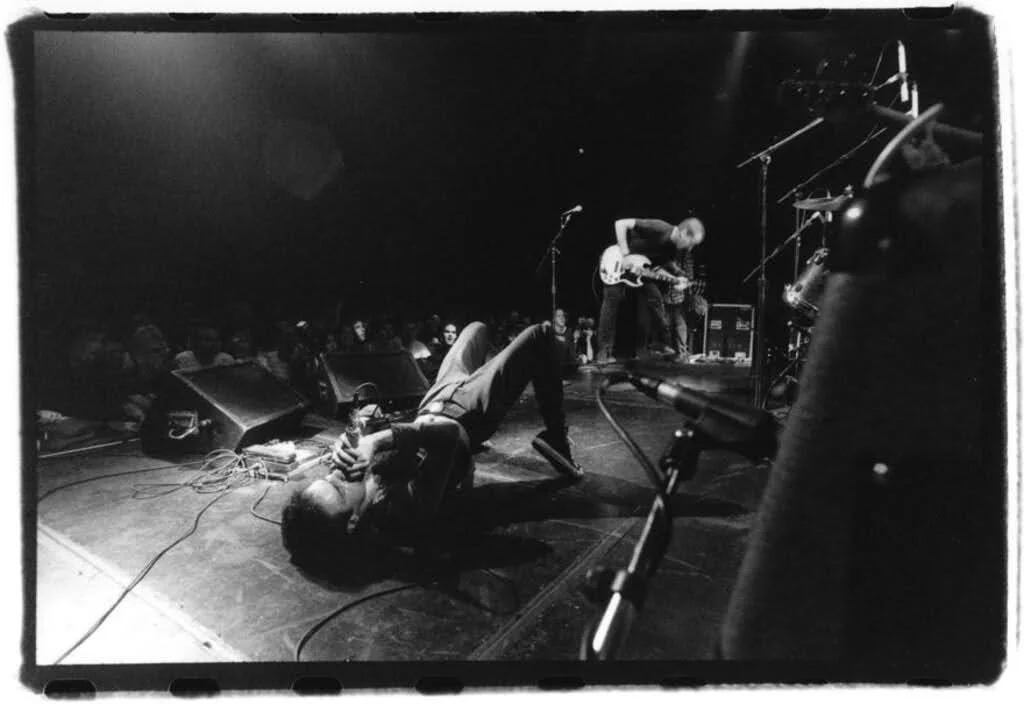

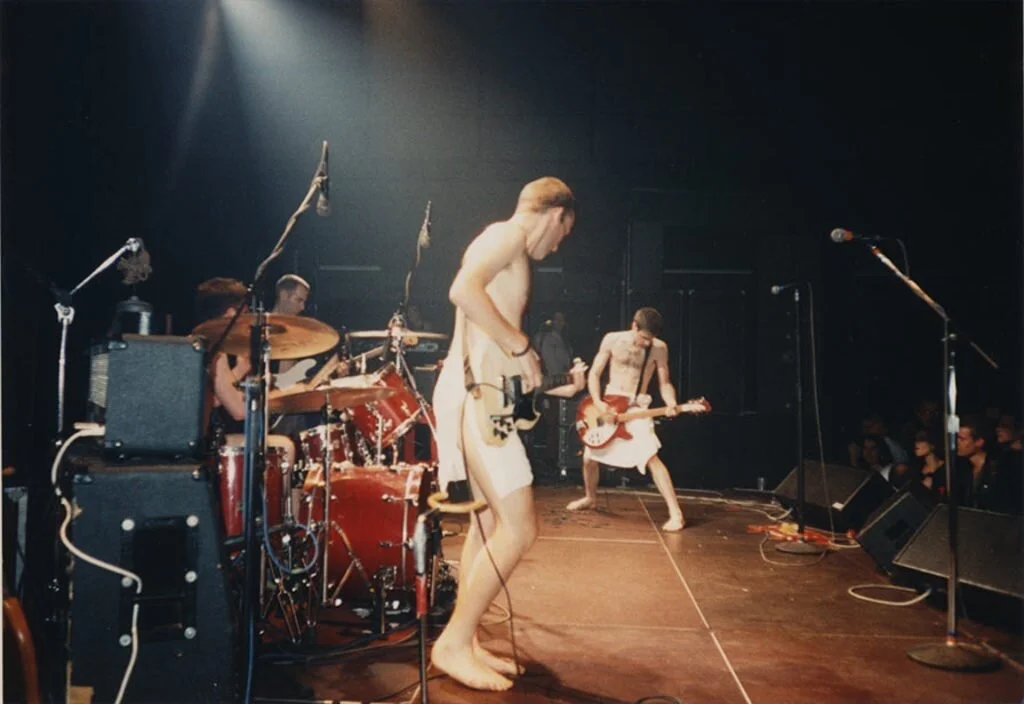

The Fugazi Live Series is the outgrowth of the fact that over 800 of the 1000 shows the band played were recorded by their sound people. Initially, they pressed a run of CDs for 30 of their shows, but with internet speeds exponentially increasing, Fugazi were able to create an archive that includes recordings of the vast majority of the shows they played for fans to purchase for the same price as a ticket (you have the option to pay a different amount but if you select it, the price defaults to $6. And everyone said this band doesn’t have a sense of humor).

For someone like me, a Deadhead but for Fugazi, the Live Series is a blessing. Alongside the archive of tracks are thousands of photos, and I’ve scrolled through every one of them. As I sat one night and listened to their set from the 9:30 Club on January 31st, 1996 (a performance with excellent sound quality, some of the tightest playing I’ve heard from them, and a smattering of Red Medicine cuts, highly recommend this one), I flicked through photos from amateurs and pros, of the band playing and hanging out, serious and ever so goofy.

I have a list of all the shows I want to buy from the archive with the various reasons attached: because there are unique lost tracks represented, because it has my favorite tracks present, or because the notes explain that something uniquely Fugazi happened that night, like the famous “ice cream eating motherfuckers” situation at Fort Reno in 1993.

What show could be more uniquely Fugazi than their first? You don’t even have to pay the 5 dollars to hear them play at the Wilson Center in Washington D.C., on September 3rd, 1987 anymore because the Fugazi Live Series has mutated its approach to sharing material once again, with shows being added to streaming services.

Their first set is, obviously, the band's first set. In comparison to the bassline of “Waiting Room” ripping out of the record, confidently introducing the band to the world, this show is the band taking shaky, hesitant steps. Starting with “Joe #1,” you hear Fugazi at that weird intersection of perfectionism and recklessness every band faces before they have learned who they are.

I read MacKaye as slightly uncomfortable presenting new songs. He dedicated the show to the eternal backbone of the band, drummer Brandon Canty, who hadn’t even become their official drummer yet. Picciotto isn’t in the band yet, but he is in the audience, and Mackaye makes a joke about having him start a fight so they can end early in case the set is going poorly. It doesn’t go poorly, but there are moments that feel half-formed due to the nature of the set. That’s because MacKaye was tired of not playing; Fugazi had to make this step.

“You can’t be what you were / so you better start living the life / that you’re talking about”

– “Bad Mouth” from 7 Songs, Ian MacKaye

That night, Fugazi played eight songs, three of which never made it past the demo stage, two were on 1990’s 3 Songs, one from Repeater, “Waiting Room,” and one that did not see a proper release until 2001. The one Repeater track here, “Merchandise,” has MacKaye ad-libbing a line during the bridge that they will add sounds of cash registers ringing over this part when they record it (they didn’t). On “Furniture,” he calls out part changes to bassist Joe Lally and Canty. Many of the parts MacKaye called for that night do not appear on the version released in 2001, but the lyrics are the same. Listening to this show at the Wilson Center feels more like eavesdropping on the band in their practice space.

In that spirit, listening to this show has more in common with Instrument, the playful album of demos that soundtracks Jem Cohen’s brilliant documentary on the band. That record is full of scraps the band is goofing around on, like their algorithm-fueled hit “I’m So Tired.” It is on Instrument and this show at the Wilson Center that you’ll hear the band at their most direct and least refined, like on “Turn Off Your Guns,” where if you miss MacKaye introducing it as a song about not killing yourself, you’ll get it when he sings “Nothing in life / could be that bad.”

“Turn Off Your Guns” is not a bad song by any means, but it is apparent from the start that it is one of the first the band ever wrote. They develop the sentiment into a more nuanced plea on 7 Songs’ beautiful “Bad Mouth,” while the melody and bassline are scavenged for Steady Diet of Nothing’s closer “KYEO.”

Have You Ever Been Free?

It is, of course, on “Waiting Room” that you hear the most potential in this show. Even with the band playing the song at nearly half the speed of the recording, even lacking Picciotto’s hype man vocals, even without the room shouting the lyrics back to the band like they would at every subsequent show. Even with all of those missing pieces, “Waiting Room” is still “Waiting Room.”

I recognize I’m slipping into hagiography about a band that fiercely would deny being mythologized, but what can you expect from a girl over 2,000 words into an essay about how much she loves Fugazi? Plus, it is a song that changed my life.

MacKaye introduces “Waiting Room” by saying, “This is a song about what the heck we could do if we did,” and telling the audience they can bend their knees to this one and move. Could you imagine “Waiting Room” requiring an introduction when, for so many, it is the introduction to the whole world of Fugazi, the opening salvo of their campaign against the music industry, against complacency, against corporate exploitation, against sexism and racism?

But that time it was just the first time “Waiting Room” was shown to the unsuspecting public—and of any introduction to “Waiting Room,” that one is the best.

“But I don’t sit idly by / I’m planning a big surprise”

– “Waiting Room” from 7 Songs, Ian MacKaye

Compare that introduction to how at the start of their final show at The Forum in London, on November 4th, 2001, the other show included in the initial streaming upload (each month the band promises to add more shows), Fugazi seamlessly transitioned from “Margin Walker” into “Waiting Room,” at the moment the drums drop out from the prior song MacKaye starts building a bridge through furious strumming. His guitar masks Lally’s signature bassline, the suggestion of the track everyone wants to hear held at bay until that drum fill kicks us off.

To answer my earlier question, the last Fugazi show is the most uniquely Fugazi. On the eve of their hiatus, Fugazi string together one of their most impeccably performed, masterfully sequenced, ideologically fierce sets ever. But first, it starts the way any good Fugazi set should: with MacKaye stepping to the mic and saying “good evening ladies and gentlemen, we are Fugazi from Washington, D.C.,” before bantering with the audience about Italian food.

When they do eventually start the show, they play with no breaks. The prior example of how they strung together “Margin Walker” and “Waiting Room” is just one excellent moment in a night full of them. Transitions span the length of their career; jumping from Repeater deep cut “Greed” to barely year-old Argument track “Full Disclosure,” late-career End Hits instrumental art rock “Arpeggiator” into mid-career In On the Kill Taker screed against genocidal imperialism “Smallpox Champion,” and Red Medicine dub freakout “Version” to 7 Songs capstone “Glue Man.” They do this all without a plan, the band having never written out a setlist.

To me, the lack of setlists is the best display of Fugazi’s artistry. The shows become a feedback loop of the band pumping a signal out to the audience and taking the crowd’s response to decide where to move next, how long to stretch a track’s noise section, and how a song gets played.

The other beautiful thing about Fugazi’s setlist-less approach is that they played everything. I’ll queue up a show and see a track like “Stacks,” that if you put a gun to my head and asked me on a good day what it sounded like you’d have to shoot me, but when it comes up in listening to a set in my head I’m screaming along that “America is just a word but I use it.”

My favorite thing about having access to these shows is that they present songs in brand-new ways. Take the performance of mid-tempo stomper “Blueprint” in the last show, played at almost double time, but in the third verse they insert a dramatic rest before Picciotto shouts “say yes” for a stretch four times longer than on the record, and elongates the “yes” in question till the tension snaps and the band comes charging back in. On Repeater, “Blueprint” seethes, full of barely repressed anger at the conventions we live under and those unwilling to challenge them. In its last minute, that anger boils over into a direct callout. But in the live setting, “Blueprint” starts at the height it reaches on the record. In their last set, “Blueprint” comes directly after Picciotto and MacKaye have had to chastise another set of crowd surfers for their “100-year-old moronic bullshit.” “Blueprint” is a direct provocation to those audience members: Are you going to continue engaging with the world in a way that privileges your experience over other people's safety? It’s all just a matter of saying no or yes.

Sewing Your Own Shirt

On their final album, The Argument, Fugazi made clear what they will always say ‘no’ to. The radio chatter and cello that frame the album set the mood for a somber, haunting affair. The Argument is Fugazi at their slowest and least musically aggressive. These qualities do not make the album lack: “Cashout” is creaky like the homes waiting to be demolished that are haunted by the people evicted for the good of “development,” “The Kill” languid like the obedient soldier waiting for orders who has done this all before, “Strangelight” whirls in the inhumanity of industry. The atmosphere of their music has never reflected the inhumane spectre of exploitation more.

But it is the final moment of The Argument, the title track, that is most important to me here, specifically the second verse:

“It’s all about strikes now / so here’s what’s striking me / that some punk could argue / some moral ABC’s / when people are catching / what bombers release / I’m on a mission / to never agree.”

As I write this, we are days out from Trump bombing Iran in an effort to aid and abet the genocide Israel is committing against the Palestinians. The consent for the strikes is being manufactured through over-inflated fears of nuclear warheads that have been claimed for decades. All the while, the Democrats hem and haw at the fact that his act was unconstitutional. They couldn’t possibly be mad at the act, though, “I’m sure you have reasons, a rational defence.”

Like MacKaye sang: I will never agree. For as long as I have been politically conscious, I have been anti-war, and I cannot abide anyone willing to blind themselves to the crimes of war so they can continue living comfortably.

“Argument” is the only logical bookend to the ideological arc sparked by “Waiting Room.” Fugazi started as an attempt to divine a true path through life. “Argument” sees them living up to that standard, fiercely refusing to accept the dominant mode just for the sake of it.

To the end, Fugazi held their ground. At the end of their last show in 2002, the band stretches out “Glue Man,” leaving the audience with a song asking them to be not just a face in the crowd, but members of a community. To not silo themselves into their homes and minds, but to exist in context. This was a band who were always in the room with their audience. Regardless of how tall the stage was, Fugazi were on the level with the people who paid to see them perform.

I was once talking with my coworker about our favorite old punk bands, and I mentioned that the only bands I wished I could have seen live in their existence were The Clash and Fugazi. He turned and said, ‘There is still a chance with Fugazi.’

But the truth is, I don’t want Fugazi to reunite.

In a recent piece for the Quietus about the new film on the band We Are Fugazi From Washington D.C., JR Moores writes, “everything has grown worse in Fugazi’s absence. It could be coincidence. And it isn’t entirely their fault. The pattern was set in motion by Reaganite neoliberalism… A few more post-hardcore records and a string of all-ages concerts wouldn’t have prevented the inevitable calamities. Would they?” Moore continues, “Still, I can’t help remembering Fugazi as a guiding hand which, in its own modest way, temporarily curbed the extremities.”

Since their indefinite hiatus, Fugazi have come to be talked about in these mythic proportions because it is so rare for anyone to get by on their own terms in this world. Fugazi have become moral guides for people, me included, because they showed us it is possible to treat each other fairly and succeed.

“How many times have you felt like a bookcase / sitting in a living room gathering dust / full of thoughts already written?”

– “Furniture” from Furniture, Ian MacKaye

Look anywhere and you’ll see Fugazi’s influence. From Jeff Rosenstock evolving their DIY anti-capitalist ethics for the digital age with Quote Unquote Records, to recent hometown benefit shows from bands like Turnstile raising money for Healthcare for the Homeless and Ekko Astral raising money for organizations advocating for transgender rights. If you are reading this right now, I guarantee you that the work of Ian MacKaye, Guy Picciotto, Joe Lally, and Brendon Canty has influenced the music you listen to. In New York, I’m grateful to have a scene of punks who refuse to do things the prescribed way, like Pop Music Fever Dream, ok, cuddle, Crush Fund, One Hour Photo, Ultra Deluxe, Eevie Echoes, Avatareden, Adult Human Females, P.H.0, and so many more.

Hell, Fugazi was a major part of why I started writing a blog about music. I didn’t want to sit around doing nothing, waiting for the opportunity to contribute. Fugazi helped me see that I had to make something for myself, and it has been the most fulfilling thing I’ve done in my life.

So, no, I don’t want Fugazi to come back because we do not need Fugazi back. What we need is to remember that these are just stupid fucking words—what you do with them, and how you get out of the waiting room, are all up to you.

Lillian Weber is a fake librarian in NYC. She writes about gender, music, and other inane thoughts on her substack,all my selves aligned. You can follow her on insta@Lilllianmweber.