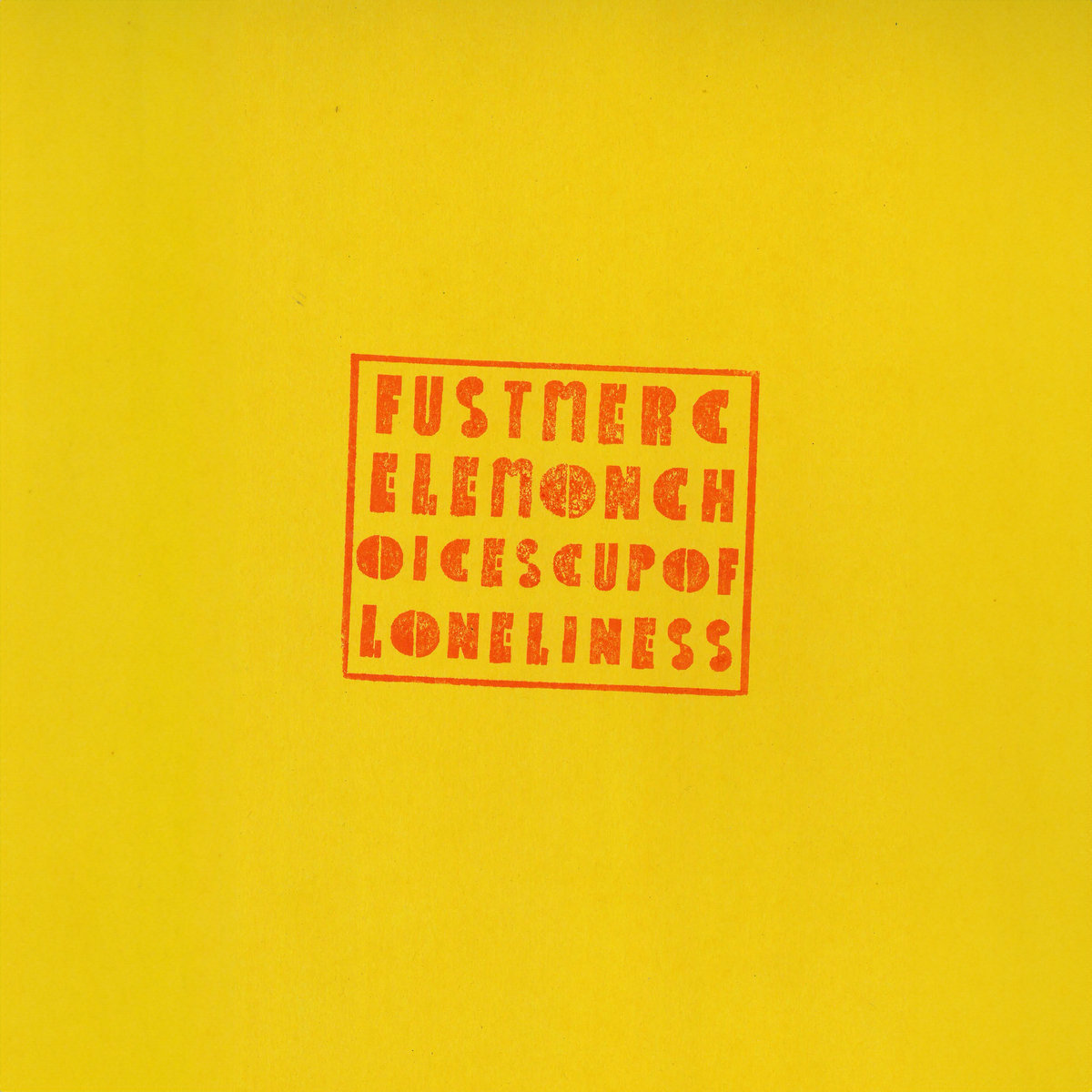

Merce Lemon – Watch Me Drive Them Dogs Wild | Album Review

/Darling Recordings

The kinetic power nature can hold for us physically, emotionally, and spiritually is nothing short of a miracle. The energy we absorb from the natural beauty of our surroundings can center our minds, heal us, and even inspire us. In a post-pandemic world, Merce Lemon felt a sense of aimlessness with her music. She used life around her for a personal and creatively reconnective experience. When she unveiled her new record Watch Me Drive Them Dogs Wild, Merce explained in a press release, “I got dirty and slept outside most of the summer. I learned a lot about plants and farming, just writing for myself, and in that time, I just slowly accumulated songs.” On her latest LP, the Pittsburgh native sings sweetly about an abundance of the earth's natural resources. Blueberry trees, birds, and rivers all coexist, with Merce tying these wonders together with a certain tranquility, acting as a reassuring voice through the stormy circumstances that life presents.

The last record we heard from Merce was 2020's jangly, alt-country-ish Moonth. Since then, the alt-country subgenre has broken into the mainstream, led by bands like Wednesday, Waxahatchee, and MJ Lenderman. Twangy indie rock has never been more in vogue than it is right now. Merce signaled her version of this evolution earlier this year, first with a split of Will Oldham covers with Colin Miller and then with the standalone slow-burner “Will You Do Me A Kindness?” Together, these songs signaled a step away from the quirky indie rock sounds of Moonth and toward something more naturalistic and folksy. On her latest album, Merce dives headfirst into the country-tinged sound, picking at the Wednesday branch with assistance from producer Alex Farrar and Colin Miller. You’ll also hear Xandy Chelmis ripping away on the pedal steel and Landon George, whose fiddle was all over MJ Lenderman’s recent Manning Fireworks.

The best example of the evolution of Merce’s sound would be the lead single “Backyard Lover,” which tugs on the heartstrings, starting with weepy pedal steel that sounds like you’re slow dancing with a partner in a middle-of-nowhere dive bar. A soft-voiced Merce Lemon delivers intimate, raw lyrics on the aftereffects of a close friend passing away, “Now I am falling to a dark place / Where just remembering her death’s / About all I can take.” Then, methodically, the band builds to an epic finish of blown-out guitars and one of the most fiery solos of the year. Throughout the record, the slow build is something Merce excels at; each and every song is a journey that she invites the listeners on, and the catharsis found at the other end makes the finish well worth the wait.

“Crow” is another song with a similar formula, with Merce singing about the “murderous flock” of birds descending onto her hometown like clockwork year after year. Momentum is constantly progressing throughout the track, beginning as a mid-tempo folk song and morphing into a raging distorted wall of guitars that match the energy of the creatures she sings about. On the same note, if there ever were a soundscape that perfectly matches the title of a song, it would be “Rain.” Adapted from a Justin Lubecki poem, the band uses a slow tempo and dreamy guitars to paint with dour grey tones. The mood is somber yet soothing, like staring outside your bedroom window during a summer shower.

Merce’s songwriting has grown with each album cycle; her lyrics have always had a persistent dread but also an idiosyncratic sense of humor, with Moonth delivering us a smorgasbord of songs about sauerkraut, chili packets, and sardines. On Dogs, she sinks further into the despair and isolation of her writing, articulating a sense of pain with beautifully descriptive imagery of people and nature. On the title track, “Watch Me Drive Them Dogs Wild,” we get loads of sensory references like the old man laughing his teeth out, the smell of bark off a fallen tree, and frozen-over leaves by a creek, all the while thoughts of marriage seem to be crushing her.

But the songs aren't all doom and gloom here; there's fun to be had, like the opener, “Birdseed,” which imagines what it would be like to morph into a bird. The lyrics touch on how freeing it must be to grow wings and soar through the sky but also how funny it would be to watch unsuspecting folk’s step onto her droppings, which is freeing in a different way, I guess. The pedal steel and fiddle work overtime here, creating an enjoyable, lush experience as the lyrics subconsciously make us more careful about where we walk now. “Foolish and Fast” is a title that Vin Diesel would be jealous of not coming up with; a perfect road trip song for driving through the mountains on a blue skyed summer day. Even on the more upbeat songs, Merce still has lines that will stop you dead in your tracks. Something as simple as “There's nothing like an open road” could be either a passing observation or intensely cathartic when you think about the freedom it implies in being able to choose your destiny.

Watch Me Drive Them Dogs Wild encourages you to go for a walk, take a road trip, or even just step barefoot outside your house, so long as you're present in your surroundings. Merce created a love letter to our natural resources, the wonders of what the earth can provide and inspire for us – something we should never take for granted. There's a yearning to be unencumbered like a bird soaring through the sky. Merce has detached herself from the pressures of everyday expectations and channeled her energy into an album on her terms.

David is a content mercenary based in Chicago. He's also a freelance writer specializing in music, movies, and culture. His hidden talents are his mid-range jump shot and the ability to always be able to tell when someone is uncomfortable at a party. You can find him scrolling away on Instagram @davidmwill89, Twitter @Cobretti24, or Medium @davidmwms.