Justin Vernon’s Ascent Into The Artificial

/How A Winding Career Led One Man From Folk Hero to Electronic Mastermind

The story of Bon Iver is almost cliched to recite at this point. Heartbroken over a breakup and frustrated with his unsuccessful music career, 25-year-old Justin Vernon embraced his inner-Thoreau and recoiled from civilization in a remote Wisconsin cabin. Over the course of a 2006 winter, Vernon spent his days in isolation hunting for his own food, contemplating his relationships, and recording his thoughts to music in a process that would eventually form his breakthrough album.

Released the name Bon Iver, For Emma, Forever Ago would come out in the summer of 2007 to widespread critical acclaim and unexpected crossover success. Led by the undeniable indie hit “Skinny Love,” Vernon’s unveiling as Bon Iver put him on the map, solidifying him almost instantly as a bona fide folk superstar. This record, along with Fleet Foxes self-titled debut, would serve as an entry point to the indie and folk genres for an entire generation of budding music fans. Despite his humble origins as a soft-spoken folk singer, Vernon has gone on have one of the most interesting, unexpected, and diverse careers in his field… but it didn’t get that way overnight.

For Emma, Forever Ago contains lots of things you would expect on a folk album: acoustic guitar, heartfelt vocals, and even some expressive brass instruments on a few tracks. It’s a choral journey through the frigid darkness of heartbreak and depression, but the greatest trick Justin Vernon ever pulled was what came next: a series of albums that grew in size, scope, and influence where each was more diverse and masterful than the last. But to fully appreciate the steps he took to get there, we have to start at the beginning.

What Might Have Been Lost

Even a cursory listen of For Emma, Forever Ago will reveal why the record became a gateway to the folk genre for a generation of fans. While music from this genre can easily become “folksy background noise” that’s pushed to the back of millennial’s campfire and bedtime playlists, Emma is anything but. Thanks to varied instrumentation, full-hearted emotion, and Vernon’s “melody-first” approach, the record reaches out and demands your attention. It’s a cozy-sounding album that you can sink into and lose yourself in.

Despite its rustic, folksy sound, one song in particular sticks out as the album’s most complicated and heart-wrenching tracks: “Wolves (Act I and II).” Coming in at track number four of nine, “Wolves” finds itself exactly halfway through For Emma, essentially acting as its emotional low-point. It’s a breakup song, yes, but after dozens of repeated listens, one moment in the song has stuck with me more than any other on the record.

The song starts just as straightforward as any other on the album, however, it’s deceptively-simple beginning quickly makes way for the densest track on the album. Opening with a single acoustic guitar, the song features a multi-layered vocal that finds Vernon harmonizing with himself. The most striking moment in the song comes halfway through the track where the bridge enters and (presumably) the second “act” begins. Vernon sings “What might have been lost” repeatedly, and the most telling moment comes at 2:50 where the third repetition bears a twinge of autotune on the word “lost.”

What might have been lost

What might have been lost

What might have been lost

Vernon goes on to repeat that phrase a total of fourteen times throughout the song, eventually interrupting himself with pained cries of “Don't bother me” that gradually build until a clatter of instruments brings the song crashing to an end.

“Wolves” is a heartbreaking song, and it’s weird to get hung up on the delivery of one word, but that single use of auto-tune planted the seeds for the rest of Vernon’s discography. They forecast what was coming next. They offered a one-word hint toward Vernon’s future, one that he may not have even been conscious of at the time, but we can point to now that we have all the pieces.

Up In The Woods

Two years after the initial release of For Emma, Vernon published an update: a four-track EP by the name of Blood Bank. Clocking in at 17-minutes, Blood Bank was only a bite-sized follow-up, but one that was eagerly devoured by Bon Iver fans who were hungry for new music.

Bearing snow-covered album art, Blood Bank seemed to rekindle the same type of tender wintery feeling as Emma, and sure enough, the release starts off just as you would expect. Opener “Blood Bank” is a frostbitten love song of candy bars, a waning moon, and, of course, a fateful trip to the blood bank. “Beach Baby” is a post-breakup song that features a spiritual lap-steel guitar outro that personifies loss and contemplation. “Babys” is centered around an ever-mounting piano line with lyrics that bear almost as many exclamation points as a Sufjan Stevens song title. And finally, the EP’s fourth track “Woods” closes out the release and signals the first time Justin Vernon fully stakes his claim on the electronic embrace.

“Woods” is lyrically-straightforward, containing one verse repeated eleven times:

I'm up in the woods

I'm down on my mind

I'm building a still

To slow down the time

It’s interesting (and worth noting here) because the song contains almost no traditional instrumentation whatsoever. Initially singing straightforwardly, Vernon croons the first verse with a voice that’s dripping in autotune.

The second verse finds Vernon harmonizing with himself, singing the same words in two different styles with two different emotions. The third verse adds an additional take, and so on until a multitude of different vocalizations are all flowing and emoting simultaneously. By the time the song reaches the halfway point, ghastly echoes reverberate through the background of the track, and the vocals at the front of the song are singing with even more passion, pain, and expression. As the end of the song nears, the momentum has built to a fever pitch and the autotuned cries all fade out into total silence.

It’s a haunting and goosebump-inducing track. While “Woods” initially came across to me as the musical equivalent of a thought experiment (“let’s see how many times I can layer myself singing the same thing”), it ends up becoming a gut-wrenching and transformative piece of art. That’s probably why Kanye West tapped Vernon to close out his 2010 masterpiece My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

Using the same lyrics as the original song, Kanye and Vernon use a similar emotional build on “Lost In The World” as a gateway to an explosive hip-hop beat laid over Vernon’s autotuned crooning and bombastic drums. This song paved the way for future hip-hop collaborations with Kanye, but also Vernon’s later electronic work.

“Woods” acted as a proof of concept that Vernon need not be tied to acoustic guitars, folk instrumentation, or even traditional song structures. Emotion and technology were enough.

Shifting Layers

While Emma and Blood Bank are insular and inward-looking, Bon Iver’s 2011 self-titled record is the complete opposite. Massive, arid, and expansive, Bon Iver is a pivot from Vernon’s snow-covered origins, yet in retrospect feels like a completely logical stepping stone.

Featuring swelling arrangements, atmospheric instrumentals, and sweeping vocals, my first listen of Bon Iver initially left me underwhelmed. As did my second listen. In fact, it took me around five years to fully-realize the brilliance contained within this record, all because it didn’t sound exactly like its folky predecessor. Now I hear the opening cascade of “Perth” and receive instant goosebumps. I see the brilliance of “Holocene” and recognize the sadness contained on songs like “Beth/Rest” are just as valid as anything on Emma… they’re just packaged differently.

Overall, Bon Iver might use less overt electronics than anything else in the rest of the band’s discography. Instead, it sees Vernon enlisting the help of his friends for a fuller and richer-sounding record that leans even harder into the choral flavors only briefly touched upon in Emma.

While there may be less overt electronics, Bon Iver is a record of layers. Vocals are layered, instruments are layers, ideas are layered. There are airy horns and explosive drums. Background vocals echo far off in the distance as ornamental swirls overwhelm the senses. It’s a feast for the ears and ends up being a complicated record that’s dense yet emotionally bare.

The album benefits from an obviously-improved budget when compared to Emma, but it finds Vernon exploring the possibilities that a studio brings. The different shapes his ideas can take outside of a traditional folk song, the different ways ideas can be transferred yet still be used to the same effect. The way melodies can be muddled, shifted, and played with until they’re nearly unrecognizable but still manage to come through… which leads to his next release.

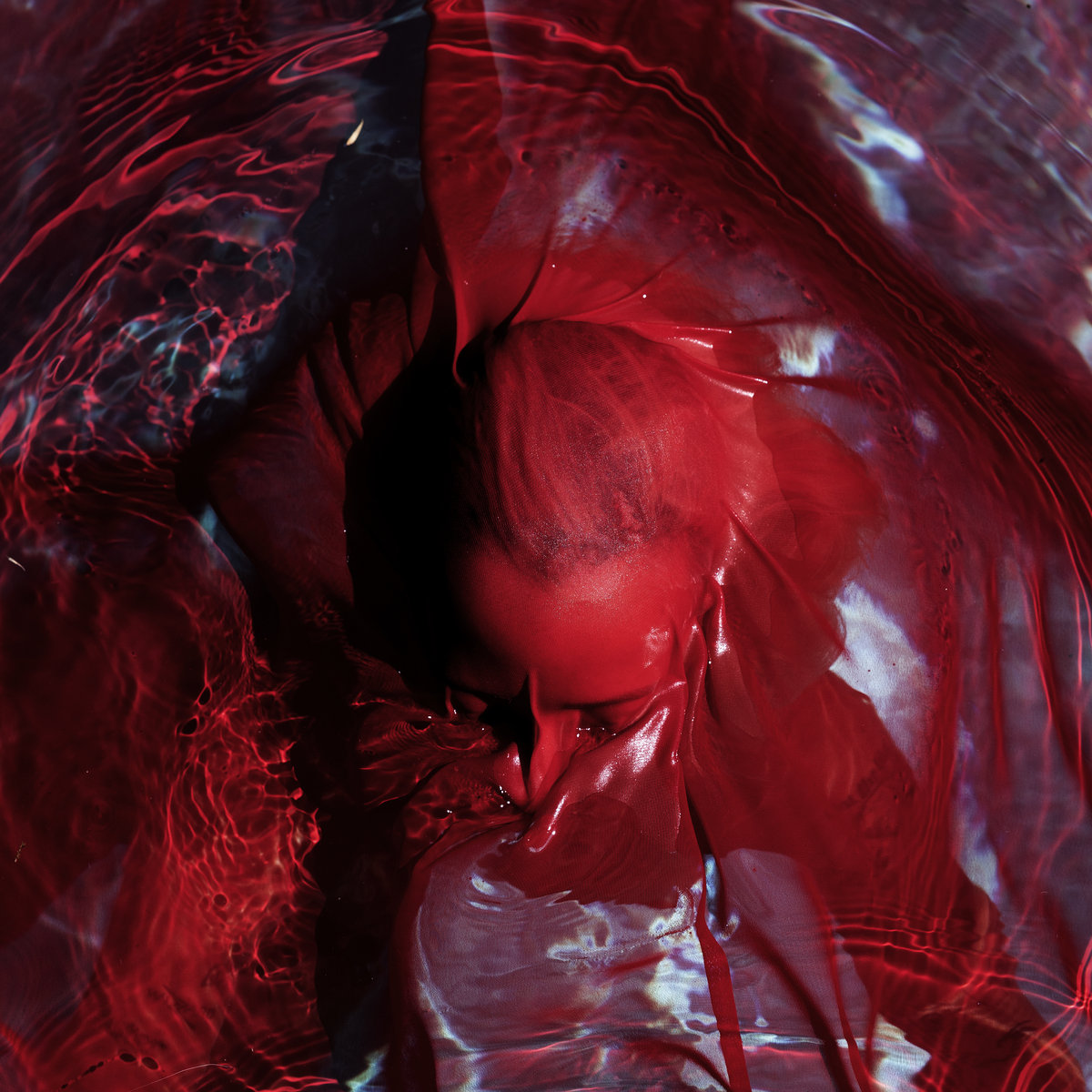

The Arrival

On August 12th of 2016, the Bon Iver YouTube account unleashed two lyric videos onto the internet: “22 (OVER S∞∞N) [Bob Moose Extended Cab Version]” and “10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄ (Extended Version).” If the names alone didn’t give it away, these songs represented a massive departure from everything that came before them. The former was a flame-engulfed crooner accompanied by dueling English and Spanish subtitles, and the later was a glitched-out beatbox spitting out distorted lines and stuttering forward endlessly.

The two songs represented the first new Bon Iver material in over five years, and fans consumed them voraciously, if not a little hesitantly. Drawing early comparisons to Sufjan Stevens’ Age of Adz, Radiohead’s Kid A, and Kanye West’s Yeezus, the two tracks were electronic, dissonant, and wholly unexpected. A left-field creation for which there was seemingly no precedent… But there was.

The day these songs were uploaded, Bon Iver’s site was completely revamped. Mostly bare, but sporting a new “bio” section written not by Vernon, but Trever Hagen, a Bon Iver collaborator and one of Vernon’s childhood friends. This new page was a long-form update captured in a TextEdit screengrab that attempted to update fans on what had happened over the intervening years. It also framed the two new singles better than any traditional press release ever could:

So, in short, 22 A Million isn’t as simple as a change in sound; it was a spiritual inevitability.

A Pathway to Understanding

I’ve built this narrative of Vernon’s increasingly-electronic career in my head for some time now. The pieces were all there from the first twinge of autotune on “Wolves” to the ever-mounting brilliance of “Woods,” but I didn’t know what to make of these disparate pieces until that summer day in 2016. When Bon Iver’s third album finally released that fall, it wasn’t just a new record from a band I already loved; it was the missing piece of a puzzle and the actualization everything that came before it.

Despite some early comparisons to genre-shifting albums of greats like Sufjan Stevens and Radiohead, I also remember reading speculation that 22, A Million wouldn’t be as good as his previous work. Of course anyone attracted to Emma’s soft-spoken folk music will find themselves lost in 22, A Million, but at that point, I had come around to Bon Iver after years of doubt and now knew to trust in Vernon completely.

What Trever Hagen was saying is that 22, A Million isn’t actually that different from the records that came before it. If there’s any trend to Bon Iver’s discography, it’s that every Bon Iver project is an album without precedent. For Emma, Forever Ago sounded nothing like Bon Iver, and 22, A Million sounds nothing like either of its predecessors. The difference here is that 22 is a complete dismantling. The first two records at least existed in the same sonic realm. Songs used familiar structures, familiar sounds, and familiar language. They were different but still comparable. Emma was a folky and intimate snow-covered cabin. Bon Iver was a wide-open sun-drenched field. 22, A Million is a meteorite.

Where previous Bon Iver songs were built around simple guitar lines, mounting drums, and easy-to-grasp melodies, 22, A Million strips songs of everything but the melody and reconstructs them from the ground up. The instruments that that are present are twisted and distorted until they’re alien and unfamiliar. There are horns, and guitars, and percussion, but they’re scratched up and broken. There are vocal melodies, but they’re chopped up and shifted around.

In fact, Vernon and his engineer Chris Messina invented a new instrument just for this record: The Messina. Better journalists than me have detailed the creation of this instrument, so I’ll just link them here along with this quote from its creator:

“Normally, you record something first and then add harmonies later. But Justin wanted to not only harmonize in real time, but also be able to do it with another person and another instrument. The result is one thing sounding like a lot of things. It creates this huge, choral sound.”

For the purposes of this article, the invention of the Messina was a major step in Vernon’s career. The Messina allowed not only for the creation of 22, A Million, but some of Vernon’s most beautiful songs. The instrument’s effect is felt all over the album, but one song in particular stands out as 22, A Million’s most breathtaking creation. A song that takes the stripped-back dichotomy of “Woods” one step further. A song that Vernon’s entire career feels like it was leading up to: “715 - CRΣΣKS.”

Lost in the Reeds

While “22 (OVER S∞∞N)” and “10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄” are great songs on their own, they also had to serve double-duty and act as a primer to what 22, A Million stood for. Once those two tracks are out of the way, the record throws listeners into the proverbial deep end with “CRΣΣKS” which, Messina aside, is done entirely acapella.

As most Bon Iver songs do, “Creeks” opens pointedly.

Down along the creek

I remember something

These lines are sung straightforwardly, but set the scene for the song and introduce the recurring phrase “I remember something.” With each following line more and more of the Messenia leaks into the vocals until the third verse where Vernon reaches a near-yell as the song explodes with passion.

Toiling with your blood

I remember something

In B, un—rationed kissing on a night second to last

Finding both your hands as second sun came past the glass

And oh, I know it felt right and I had you in my grasp

Put simply, “715 - CRΣΣKS” is sublime. The song is a beautiful and one-of-a-kind creation that represents millions of branching paths all converging to create something practically too beautiful for this world. If Vernon hadn’t shown the propensity for electronics, his path wouldn’t have led to this song. If the Messina hadn’t been invented, this song wouldn’t have been possible. If Vernon hadn’t stowed himself away in that cabin over a decade ago, these feelings would not have been realized.

“CRΣΣKS” is the ultimate marriage of humanity and technology. The entire time you’re witnessing Vernon’s emotion breaking through with each word and waiting to see what comes next. He leads the listener with each line, forcing them to lean in closer and closer until he violently breaks through the cold, indifferent wall of technology. It’s explosive, fragile, and heartbreaking. It’s a song that never fails to make me feel, and there’s something to be said for that.

Never-Ending

Vernon’s journey from folk hero to electronic mastermind was a long and winding multi-year-long process. It’s a journey that continues to this day as he tours, performs the songs live, and even on side projects like Big Red Machine where Vernon and The National’s Aaron Dessner both encourage each other along their respective increasingly-electronic journeys.

The saga of Bon Iver has been a thrilling story to watch over the past decade. From the first wintery guitar strums of Emma to the final piano notes of 22, A Million, Vernon has weaved a multi-part epic on heartache and the human condition. Each song peeled back another layer, revealing the human behind the music, and that unfolding has been a fascinating, touching, and rewarding thing to witness.

While I hope we have many more years of music from Vernon, 22, A Million is undeniably an incredible third-act in the discography of Bon Iver. It’s more than folk music. It’s more than indie music. It’s more than electronic music, art pop, or any other label you can place on it. 22, A Million is human music.