Heart Sweats II: Another Swim Into The Sound Valentine’s Day Mixtape

/Rip open that box of chocolates, pour out some red wine, and grab a handful of chalky heart-shaped candies, ‘cause we’ve got a lovey-dovey Valentine’s Day roundup for all you hopeless romantics out there. In celebration of the world’s most amorous holiday, we asked the Swim Team what love songs are hitting them particularly hard right now. Much like last year’s edition, the result is a beautiful and wide-ranging mixtape from the Swim Team directly to you.

Alien Boy – “Seventeen”

Get Better Records

Falling in love is stupid. It’s one of the most senseless things you can throw yourself into, but that’s how it has to be. Love is going to embarrass you, humble you, and terrify you; it's going to make you act crazy and hurt in ways you never thought possible… It’s also the best thing in the world. Before there can be love, there must be that weird liminal period where you’re not sure what’s going on within yourself or with this person. You’re not sure if this feeling is one-sided or just something you’re thinking too much about and building up in your head. Most people call this the “crush” stage, and it can be just as exhilarating as it is disastrous.

That feeling of a new relationship, of fresh, dumb, pure emotional adoration is captured perfectly in “Seventeen” by Alien Boy. It’s a song embodying the feeling of adolescent love, the type of love that takes over your body and abducts your mind. The bouncy guitar jangle acts as the heartbeat while the bass and drums add a propulsive, restless energy like a leg you can’t stop bouncing. Every waking moment, you’re consumed with this sense of possibility; all the imagined realities and possible futures. You need reckless abandon. You need to let it out, or you’re gonna implode. You’ve gotta love like you’ve never loved someone before. It’s all or nothing.

– Taylor Grimes

Brahm – “I will find you”

Self-Released

Screamo is not typically the place you look to for romantic love songs. Despondent longing, sure, plenty of examples there, but espousals of deep care and adulation not rooted in agony can be a bit hard to come by. Which is really a shame. A genre as complex and passionate as this owes itself to have at least a few tracks that explore love in its connective tenderness. This is why when Brahm released “I will find you,” I was very quickly moved to tears. Here, so much of what makes this music powerful was being channeled into a grand exultation of the relationship between the singer and his now-fiancée, concentrated into an incantational promise: “I will find you / In every lifetime / Just like we / Were always meant to.” Screamed, repeated, driven up into a crescendo: “I will find you” is one of the few screamo songs that feels truly pure in its love while claiming and owning all the sonic intensity one can expect from a legendary band like Brahm. Tender, subtle, gentle, then explosive. Though few in number, screamo love songs are immense and absolutely worth weeping over on our most saccharine of holidays.

– Elias Amini

The Meters – “Mardi Gras Mambo”

Warner Records

Every few years, like this year, Valentine’s Day coincides with the final round of Mardi Gras festivities. It always kind of irritated me when that happened. Mardi Gras is such an insular holiday with days upon days of nonstop partying and local antics, while Valentine’s Day’s appearance always felt like it was abruptly intruding—a pink and red reality check while I’m dealing with purple, green, and gold. I have softened on this position over time and have personally compromised by including Mardi Gras songs amongst my pantheon of the greatest love songs. When measuring how much love I feel towards my favorite Mardi Gras songs, I think I love The Meters’ cover of “Mardi Gras Mambo” the most. Quite frankly, the little funky keys part at the beginning is one of the most beautiful things put to wax and best enjoyed with a daiquiri in hand. It's an old song, somewhere around 70 years old, meaning that it’s been played for generations of New Orleanians like me. This means that everyone knows it, everyone sings it, and everyone does the same little dance to it while standing on the streets. Love is in everything, and love is everywhere, but love is especially in the Mardi Gras mambooooo down in New Orleans.

– Caro Alt

ManDancing – “I Really Like You (Carly Rae Jepsen cover)”

Something Merry

Sometimes people joke about Carly Rae Jepsen being the queen of emo, except I’m not joking. In 2015, she blessed the world with an instant-classic pop album, Emotion, absolutely overflowing with timeless desire, courageous sincerity, and selfless love. Three short years later, Something Merry and 15 talented artists orchestrated a cover album, with all proceeds donated to Immigration Equality. EMO-TION redirects the original album’s skyscraper-high pop sensibilities into intimate articulations for any occasion. In their cover of “I Really Like You,” ManDancing takes the already perfectly unsure, desperate, brave lyrics and fills them with bated breath, yearning, and a passion literally begging to be met. The guest vocals from Em Noll in the chorus mirror lead singer Steve Kelly’s feelings, not knowing if falling so fast is a good idea, and not really caring.

I met my partner at a rock concert, and after our second date, 72 hours later, I said to her, “I think we’re in trouble.” What began as innocently getting to know each other quickly spiraled into a long-distance relationship spanning the Atlantic Ocean. These days, our distance only spans Iowa, and even then, we’re lucky enough to see each other almost every month. This song reminds me of when we met, let go of everything, and fell for each other.

ManDancing, king of this single; Carly Rae Jepsen, queen of emo music; Annie Watson, queen of my heart.

– Braden Allmond

Oso Oso – “skippy”

Self-released

This just in: love is just liking everything about a person?

I like how you’re a little messy when you’re in your comfortable spaces–like how you leave your socks by my bed, yet you’re so put-together everywhere else. I like how you know that I can be a bit of a fuck-up sometimes, but you see who I am on the inside and, even more so, who I’m trying to be on the outside. I like the songs you show me, even when I don’t like the genre. But I like them because you showed them to me. I like how every melody of every song I hear is a sunny-bright hook, like literally every line of music and lyrics in “skippy” by Oso Oso. With you in the world, every song is catchier, every bite tastes better.

Most of all, I like the way that it could only be you and that you knew it before I did. I might be late to our party, but I’m grateful and lucky to go with you on my arm.

– Joe Wasserman

Touché Amoré – “Come Heroine”

Epitaph Records

I’ve never been one for love songs. I often find them saccharine, bogged down by cliche emotion and sticky with reductive lyrics that I’m sure I’ve heard elsewhere. I’ve been in love with my husband for nearly a decade, and it’s nearly impossible to find a song that accurately captures the enduring and torrential force of that kind of love, yet Touché Amoré manages to do just that in “Come Heroine.” The song crashes forward like an avalanche, rushing headlong into a crashing ocean of honest declaration: “You brought me in / You took to me / And reversed the atrophy / Did so unknowingly / Now I’m undone.” I’ve repeated this raw confession countless times, the rhythm of my heart counting the syllables. Love has disarmed me, shown me my weaknesses, and simultaneously strengthened me. “When I swore I’d seen everything / I saw you.” And even after a decade, seeing my husband every morning feels like the first time I realized I was in love with him. Even when the day comes that I finally have seen everything, I know it will still pale in comparison to him. Maybe I am one for love songs after all.

– Britta Joseph

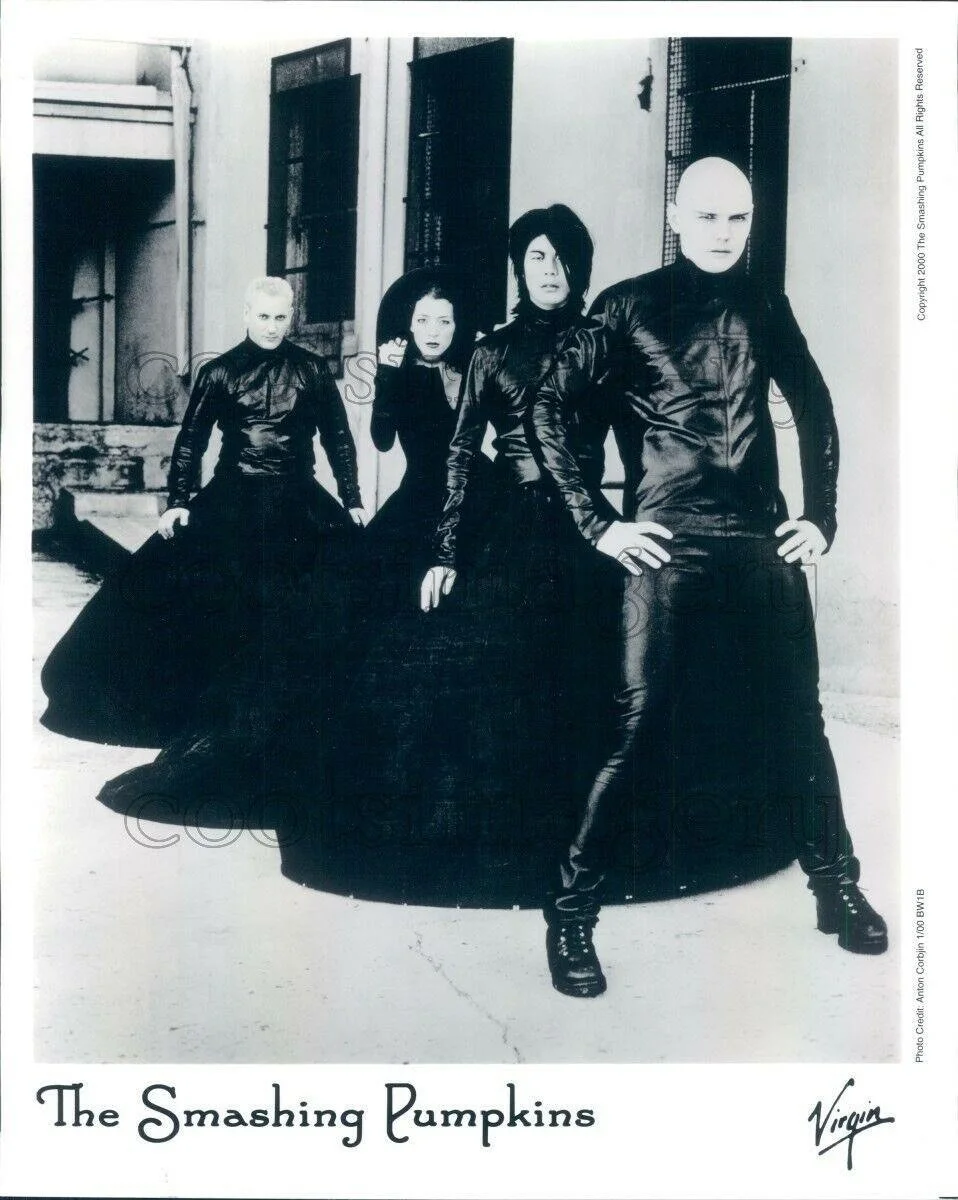

The Smashing Pumpkins – “Stand Inside Your Love”

Virgin Records

What does it actually mean to actually stand inside someone’s love? The hell if I know, but what I do know is that in the Y2K era Billy Corgan still had his fastball when it came to writing pop songs. “Stand Inside Your Love” is a shining example of this. It’s catchy as all get out, the lyrics are simple and easy to remember, I mean, I don’t know what else to tell you, it’s just a groovy listening experience. Those classic Pumpkins' new wave guitar textures still hit like an anvil to the heart to this day. It’s one of those love songs that still has some oomph when listening. Do yourself a favor and play this for your partner for Valentine’s or cruising around town on date night. You can thank me later. If they love the song, tell them that David sent you. If not, lose my number.

For extra credit, if you’re into the vaudeville subgenre, this song’s music video will scratch every itch you could ever imagine.

– David Williams

Kings of Leon – “Find Me”

RCA

My partner and I have been together for almost a decade, which means there are a lot of songs to choose from that have been cornerstones to our relationship. I’d been finding it difficult to choose the best one to write about this year, and I suppose it took the pressing deadline of this article’s publish date to bless me with the source. Kings of Leon have unabashedly been one of my favorite bands since I was in grade school, despite their more recent material falling a bit flat for me. But it’s actually a song from their 2016 album WALLS that comes up quite a lot in our musical lexicon with one another, a song that finds the Followill family doing their best Interpol impression, of all bands. “Find Me” is without a doubt the best piece of music the band has released in the last ten years, an upbeat rocker that doesn’t mute Caleb’s signature voice like their other latest singles do. The chorus, which is largely anchored by the question “How did you find me?”, is an effervescent feeling we share and echoes the gratitude we carry that we found each other at all. In the second verse, Caleb pleads, “Take me away, follow me into the wild with a twisted smile, I can’t escape. And now I got you by my side, all my life, day after day.”

The WALLS Tour was one of the first concerts we ever went to together, and the jolt we got when they played “Find Me” kept us going throughout the rest of the 2+ hour set. I am gushingly lucky to have found my one, even if the “how” of it all doesn’t have a definitive answer. Although, it may be hard sometimes to find each other at Costco.

– Logan Archer Mounts

Angel Olsen – “Spring”

Jagjaguwar

“Don’t take it for granted, love when you have it,” is a line that has felt like a mantra ever since my first listen to this track on Angel Olsen’s 2019 album, All Mirrors. Sometimes the songs most indicative of love are the ones that describe the spaces in between it, the moments longing for it, and the times when it’s found, even if its presence only exists in a brief moment. “Spring” is downtempo enough to soundtrack a slow dance, but as the keys and orchestral production swell, it’s easy to get lost inside of due to its musical syntax and structure. It’s the auditory equivalent to the head rush of a kiss; it overtakes you but brings you back down from it gently. Even as Olsen reflects on others who may have found “it,” her optimism reaches the song’s ultimate peak of vulnerability as she plainly asks for it: “So give me some heaven just for a while, make me eternal here in your smile.”

– Helen Howard

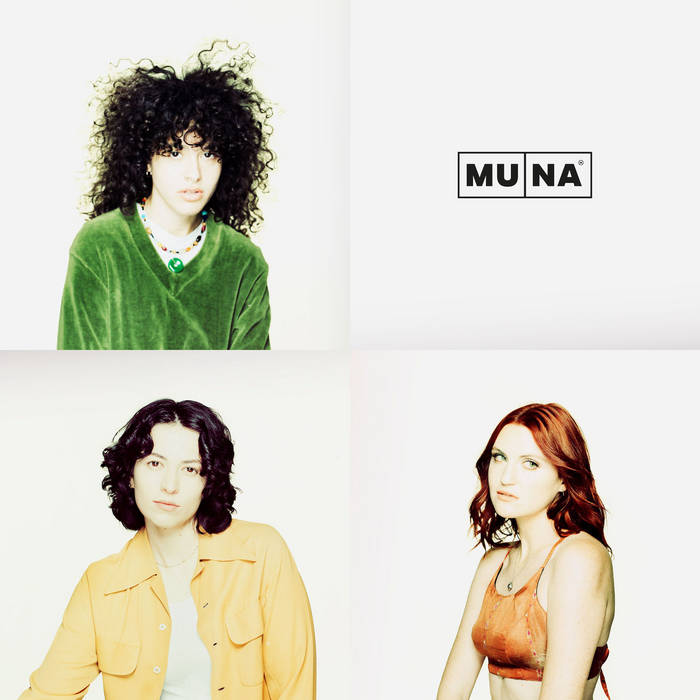

MUNA – “Kind Of Girl”

Saddest Factory Records

Valentine’s Day can be hard when you’re single. I spent most of my twenties in a committed relationship, and now I can’t remember the last Valentine’s Day I celebrated that lined up with me being in a romantic relationship. However, even if you’re not romantically entangled on February 14th this year or any year, what’s most important is your perspective. I’ve been in and out of relationships quite a bit since my last major relationship broke off, and when any of those relationships have fizzled out, I found myself clinging to negative self-talk as I often do. “Kind Of Girl,” off of MUNA’s self-titled record, is a song I cling to when I need a reminder that it’s more important than anything to treat myself with grace and accept my flaws as human. Despite their catalog being full of sad queer girl music, this track takes a softer approach to sitting with your emotions. I’m the kind of girl who feels her emotions so intensely, both when falling in and out of love, or even in the presence of the slightest crush. A connection can simply run its course, yet I have to tell myself all the ways I should’ve done things differently and that I’m better off avoiding further entanglements. I’m glad I have MUNA to remind me in those moments that I need to love myself harder. I need to be gentle with the kind of girl I am, maybe lean into one of my many hobbies, and keep my heart open to the next person who wants to connect with me – and this time, let them.

– Ciara Rhiannon