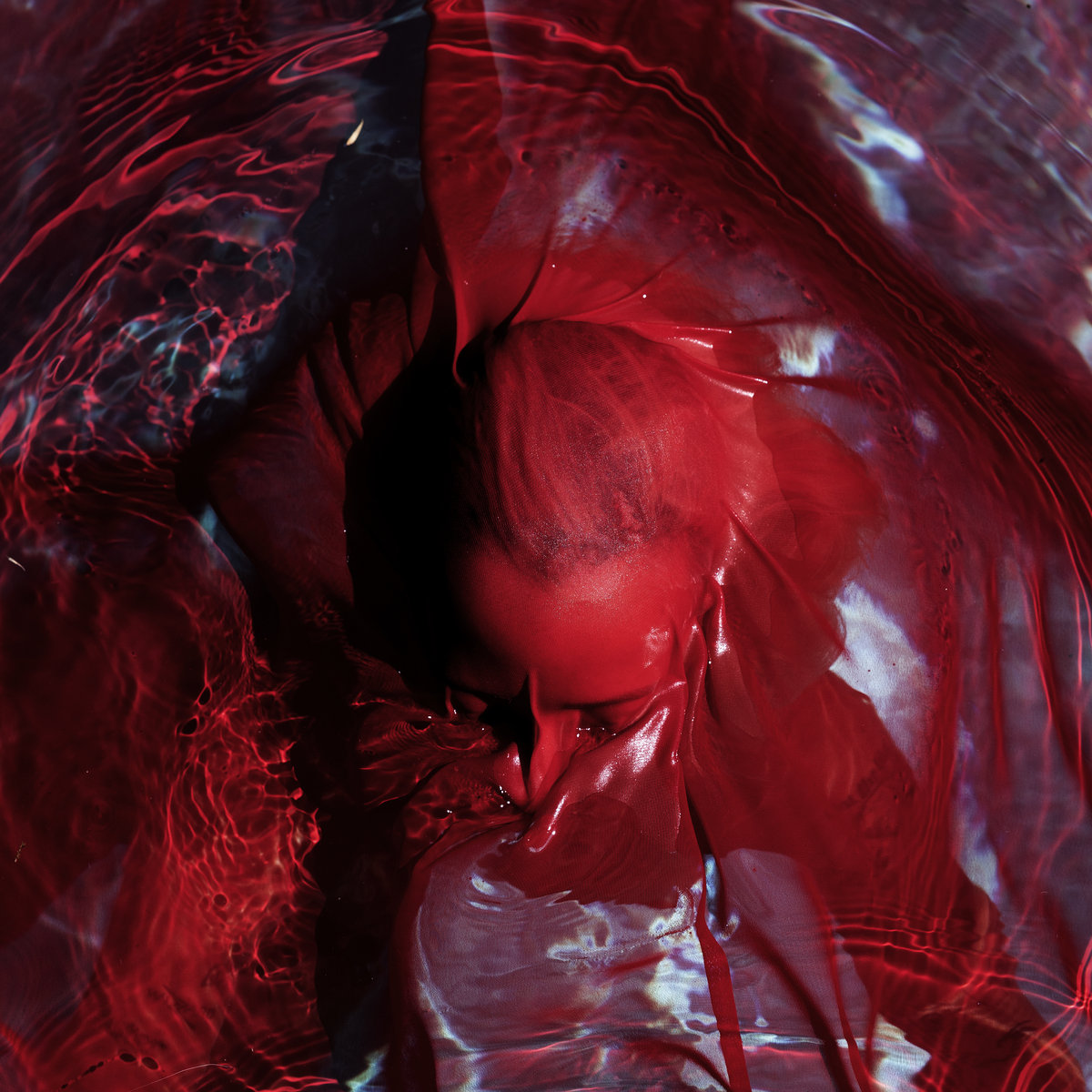

Blackwater Holylight – Not Here Not Gone Review

/Suicide Squeeze Records

When it comes to stoner rock, sometimes it feels like there’s little room for the form to expand. So often, bands fall into tar pits as they rehash the same trite lyrics and recycle the same five sludgy riffs. For titans like Sleep, this genre can be taken to bong-ripping heights, but other acts like The Sword iterate until they become parodies of their earlier, more exciting selves. If they are averse to marijuana mysticism, a band might instead go down the path of the thousand-dollar leather jacket and embrace more of a desert rock direction. Queens of the Stone Age make this look cool, but most of the time you’ll end up sounding like Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. So how do you inject new life into a style that often reads as riff-by-numbers? You abandon it almost entirely.

That’s exactly what Blackwater Holylight have done. On their first two albums, the Portland, Oregon, group’s sound was dripping in bluesy, chugging 70’s hard rock. They were proficient in their Sabbath worship, but not altogether original. In fact, 2019’s Veils of Winter is so entrenched in the desert-doom sound that it literally has a song titled “Motorcycle.” These are good albums, but it’s clear that the risk was there for them to become trapped in the endless cycle of cannabinoid riffage. The band’s third album, Silence/Motion, was a massive reimagining of their music as the group became darker and more dreamlike, adding in elements of prog and shoegaze. The result is something simultaneously refined and menacing, but what makes it so impressive is that it’s very clearly the same band that made the first two records.

On Blackwater Holylight’s new album, Not Here Not Gone, the group is continuing to evolve their artistry while remaining true to their roots. After relocating to LA and working with producer Sonny Diperri (Narrow Head, DIIV, Emma Ruth Rundle), the trio has cultivated a vicious doomgaze sound that is equal parts punishing and ethereal. The album opens with “How Will You Feel,” which immediately signals that Blackwater Holylight is continuing to push the limits of their expression. The track features fuzzed-out, crunchy guitars that are more akin to early My Bloody Valentine than Truckfighters as singer Sunny Faris’ voice floats serenely above the chaos.

On tracks “Bodies” and “Spades,” guitarist Mikayla Mayhew blurts out concussive, mosh-inducing riffs that are backed by airy synth work from Sarah McKenna. It’s this constant contrast that makes the songs on Not Here Not Gone so engaging; just when you think you’ve got them figured out, they shift into a new direction. Single “Fade” finds them branching out into the vast world of post-rock with a confidence that would have you think they’ve been making songs like this for twenty years. Album interlude “Giraffe” is the band’s biggest experiment yet as they jam over a beat from Dave Sitek of TV on the Radio. The collaboration results in a slice of industrial rock that could fit in seamlessly on the tracklist of The Fragile. Despite all of these progressions, Blackwater Holylight hasn’t forgotten that, at the end of the day, they descend from Black Sabbath. This is best heard on the seven-minute closer “Poppyfields,” which weaves elements of black and doom metal and gives Eliese Dorsay an opportunity to truly beat the shit out of her drums. All of this is done in the service of creating a brooding, tension-filled piece that ends the album on a powerful note.

All of this is what makes Blackwater Holylight such an impressive band. Rather than coming out of the gates hot on their first album or two and then fizzling out in attempts to recapture that energy or flailing through desperate experimentation, the group has steadily and deftly adapted their sound. They’re the kind of band that makes you want to continue to follow their career because you’re actually excited to hear what they’ll do next, rather than clenching your jaw in hopes that they stick the landing. While Blackwater Holylight might not be a textbook desert rock or stoner doom band anymore, they fit in at Austin’s Levitation Fest as much as they do at Roadburn in the Netherlands. Blackwater Holylight refuse to be contained by the constraints or expectations of genre, charting their course on their own terms. They're far from the first musicians to do this, and they're certainly not the last, but in a genre that is loaded with copycats, they're a shining example of changing and molting until you reach the truest version of yourself. Odds are, people will recognize that and be drawn to it because when everything else can be found in excess, the things that are actually unique speak for themselves.

Connor is an English professor in the Bay Area, where he lives with his partner and their cat and dog, Toni and Hachi. When he isn’t listening to music or writing about killer riffs, Connor is reading fiction and obsessing over sports.